Fifty years ago tonight, on Christmas Eve, violent weather swallowed up the east coast of the United States, locking it down and immobilizing it.

My mother, in a surprising show of affection, had organized a surprise party on the occasion of my father’s fiftieth birthday; together, she and I had gone shopping for his gift — the first Polaroid SX-70 ever made — and carefully hid it in the apartment where he’d never find it. But because of the storm, the deli deliveries for the party were halted. My father’s parents couldn’t make the trip from Brooklyn. My very formal aunt got soused on a single glass of white wine. My mother flirted with a downstairs neighbor named Buck, who sang her The Shadow of Your Smile in the kitchen where she was trying to make fondue. My father’s boss, Eli, broke open a bottle of good single malt Scotch and drank most of it; I have a vivid memory of him sitting on a low chair in the living room wearing a fez and playing my bongo drums, which were wedged between his knees. When the cake was finally festooned with candles and brought into the living room, my father wept and wept as his friends slurred their way through Happy Birthday and someone made the inevitable joke about my father (a nice Jewish boy) and Jesus (also a nice Jewish boy) sharing a birthday.

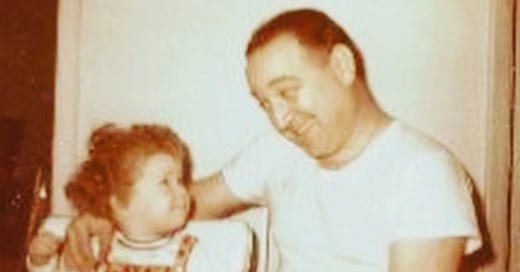

My father was generally a terrible and dour birthday celebrant, and remained one until his dying day. He loved being surrounded by his friends and colleagues, even though most of them, by the time the evening ended, were inebriated and forced to stay over because of the weather. He could not believe he had made it to fifty — he told me this many years later, over very dry gin Gibsons at Rolf’s — and the idea of having half a century under his belt both thrilled and disoriented him: he was still the same twenty-year-old night fighter pilot he’d been thirty years earlier, in 1943, still the young man given to ferocious depressions and bawdy humor, and the expectations and various disappointments that often paralyzed him in a dark knot of craving and envy. He was a complicated man, and for many years we had a complicated relationship, but one thing was for certain: aside from my wife, he was my personal miracle, and had it not been for him, I would not be sitting here writing this.

The son of an Orthodox cantor who lost many members of his family in the Holocaust, my father’s relationship with Christmas was dichotomous; he absolutely loved the holiday, and was utterly guilt-ridden about it. Although I was raised in a devoutly secular home, I had no tree growing up; he could not and would not go that far. In the same breath, he would rattle off a list of the best places in New York to hear The Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols when I was older — Saint Thomas’s, St. John the Divine — which he insisted had to be followed by a quiet bracing walk. Still, for him, Christmas had far less to do with religion, and everything about the possibility of light continuing on in the dark as Adam Gopnik once said. It was about beauty and humanity and miracles, and by the time I was fifteen, I had listened to Lessons and Carols on WQXR so many times that I could recite it from beginning to end, including that terrifying and familiar situation with King Herod in Matthew 2.

One thing was for certain: aside from my wife, he was my personal miracle, and had it not been for him, I would not be sitting here writing this.

It was metaphor — I knew it was — and this was exactly my father’s point: listen to the music and the stories, understand that in the darkest of times, light will be upon us. He had experienced this firsthand: he had survived an incredibly dangerous job as a pilot during the war; he learned to live with the depressions that were so hard for him; he eventually, for the most part, put down the Gibsons; he found true love late in life; he saw me settled and happy after many years alone, and loved the woman who would become my wife a few years later. It breaks my heart that he would not live long enough to stand beside me when Susan and I were married, but I believe he was there, because I believe in those sorts of things.

My father would have been 100 today and we have spent it in a way he’d approve of: we listened to Lessons and Carols from Kings College, as we always have for twenty-four years. The radio has been on all day, the gorgeous baroque Christmas music filling the house, and I am salting the roast for tomorrow’s Christmas dinner. My only wish: that my father was at my table.

* The Savior must have been a docile gentleman (1487), Emily Dickinson

The Only Standing Rib Roast Recipe You Will Ever Need

After the fifth or sixth time — each time with success — I made this roast, I decided to go public with it one Christmas a few years ago. A couple of hours later, I received a note from Nigella Lawson, who was apparently so taken with what it looked like in my photo (above) that she decided to make it according to this recipe (which is actually a version of any number of oven-off recipes, most of which work very well). When Nigella said that she was going to make it for her holiday meal, I nearly had a heart attack. What if it didn’t work? What if she wound up with a massive and expensive roast so overdone that she could floss with it? Luckily, it worked, she was happy, and so was I. (And relieved.) This recipe has been floating around in my files for a very long time, and I’m not entirely sure I know its origin. All I know for sure is that it works perfectly for every size standing rib with the exception of a single rib — which is really just a steak — provided you follow the recipe exactly.

Start with a prime standing rib of the best quality you can find. Salt and pepper it well. Let stand uncovered overnight in the fridge. Weigh it (after the overnight). Multiply its weight by the number five. Whatever that number is, write it down. Don’t ask. Let the roast rest at room temperature for three hours before cooking. Don’t rush this. Salt and pepper it again. Crank your oven up to 500 degrees F. Place the roast on a rack in a roasting pan, and roast at 500 degrees F for the number of minutes you got by multiplying its weight by the number five. When you hit that number and your timer dings, shut the oven off for two hours. Don’t dare open the oven door for any reason. No excuses. Go about your business. At the end of two hours, remove the roast and this is what you’ll get. Drape it, let it rest a bit, then slice and serve with horseradish sauce.

I just discovered this, after identifying with your piece on addiction of rage. My father, also a WW II pilot, would have been 100 on Thanksgiving this year.

Not sure if this would interest you. I'm a Masters In Gastronomy student at Boston University. I heard the program is looking for a professor for a Masters level, online Food Memoir class in the Spring of 2025. Yes, 2025:) I can put you in touch with the head of the program if interested. Happy New Year.