I got home late yesterday from eighteen hours in Washington, DC, where I was doing a book event for Permission at Politics & Prose, a bookstore that I truly love. I was actually worried about going; for one thing, we were planning on driving, but if you’ve ever driven to DC from New England, you know why that would have been a bad idea (an average trip can take anywhere from seven to thirteen hours, and it’s anyone’s guess). For another, Amtrak prices have skyrocketed, perhaps because no one wants to fly anymore. For another, I was dreading coming face to face with the monuments to democracy that I’ve seen countless times over the years — the Washington Monument, the Lincoln Memorial — and all of the amazing Federal buildings reduced to apparent shells of their former selves. Like, for example, the Andrew Carnegie Library, which is now an Apple Store. (I would have linked to the Carnegie Library website, but it appears to have been taken down.)

We want to inspire the artists, writers, and philosophers who maintain our collective ability to dream. A society unable to dream lacks the imagination to know what freedom looks like. - Jonathan Simons

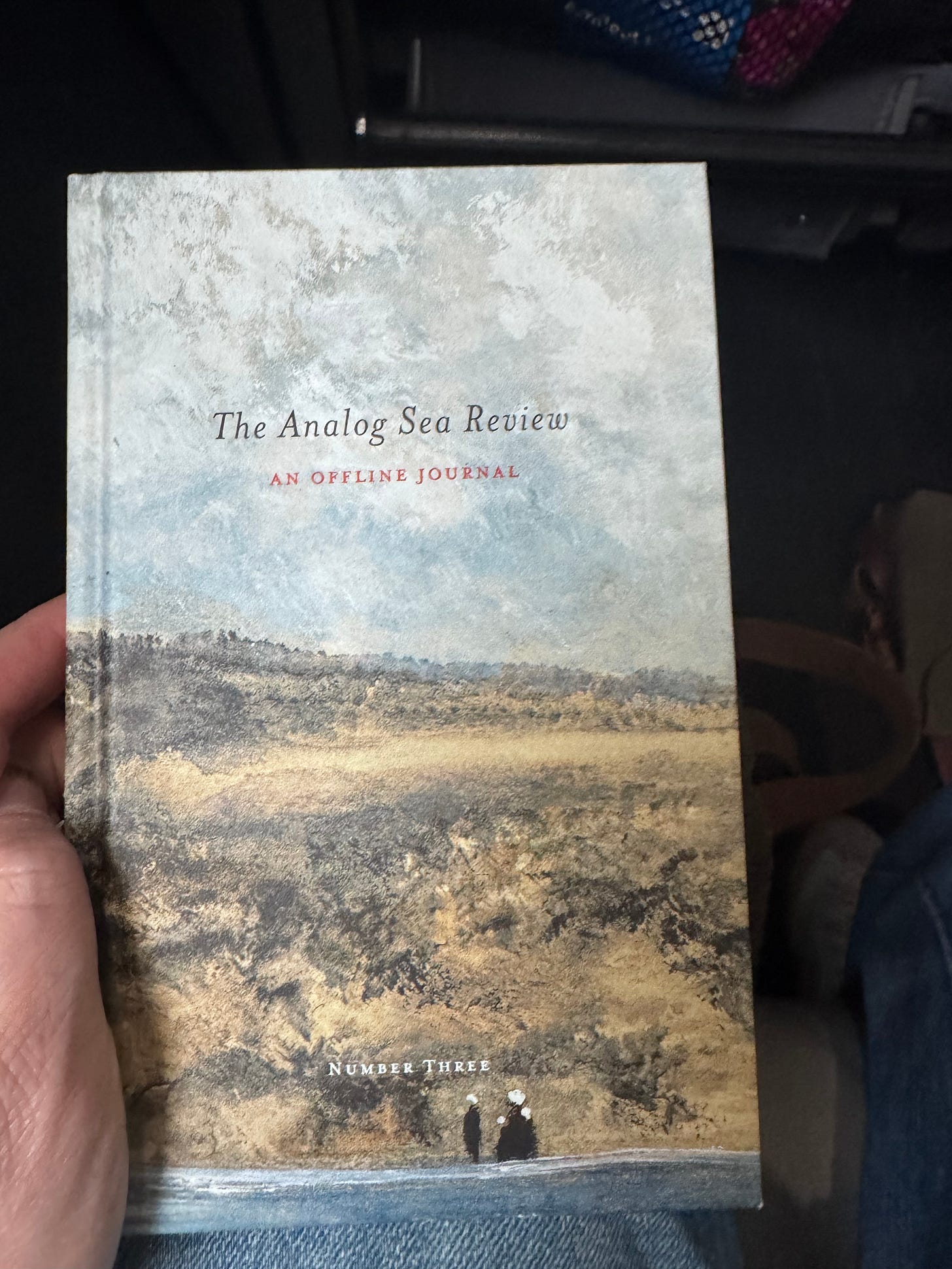

So train it was, and it was the right decision: I love train travel. There was nothing to do but read and look out the window and doze, and on our trip down I used most of those five hours to research my next longer project, and scribble notes (in pen, on paper) for my next two essays. On the way home, I read The Analog Sea Review, Number Three, a small-format, hardback journal that collects excerpts from every analog-appropriate writer, including some of my favorites, like Anne Fadiman, Barry Lopez, Robert Macfarlane, William Stafford, Wim Wenders, Gaston Bachelard, Jackie Morris, Rilke, Borges, and others. The Analog Sea Review is not easy to find, but there they were, at Politics & Prose, and I picked up the two that I didn’t have.

In the introduction to this volume, editor Jonathan Simons writes of the dangers of digitalia — ascribing human qualities to that which might be algorithmically designed to react to you like a human in response to (for example) the isolation we experience in our postmodern lives. Right now, Simons writes, millions of people are confessing to their gadgets their loneliness or their fear of dying, and the gadgets are responding with music and discounts.

He goes on:

Preserving the printed word is of great significance, along with the physical spaces where humans look other humans in the eye, where civil dialogue and undivided attention are privileged, and where thoughts and imagination have space to meander and roam….We want to inspire the artists, writers, and philosophers who maintain our collective ability to dream. A society unable to dream lacks the imagination to know what freedom looks like. Eliminate the dreamers and we fall too easily for fascism and war. How desperately we need the strength to dream and the artists and thinkers to show us how.

Simons’ prescient words were written in 2020.

And yet.

Here I am, writing this on a digital platform that I actually love — I love Substack, even with its hiccups — because it has connected me with writers I would have never otherwise come in contact with, and readers who have enriched my life immeasurably. I have met many of them at my book events. Sure, there are pockets of nasty just as there are everywhere. But for the most part, there is some excellent writing here by people I both love and have come to love. I look forward to reading Sari Botton’s Oldster and Memoirland, Katherine May’s The Clearing, Sam Baker’s The Shift, Horticulturalish, Susie Middleton’s SixBurnerSue, Wendy Macnaughton, Alice Elliott Dark, and so many others. I love Tom Cox’s work and Emily Nunn’s Department of Salad. My dear friend Sara Jenkins is here (and anyone who loves Italian cooking and foodways needs to read her). Karine Polwart, one of my favorite musicians and artists is here now, and Rosie O’Donnell is now writing missives from Ireland that prove the fact that the Irish are (almost) all poets. And then there’s Mary Trump and Timothy Snyder and The Contrarian and Paul Krugman. But for the most part, I come here for the words that compel me to look humanity in the eye when I really do not want to, to get out and live, to understand that, at its best, Substack is the digital manifestation of the writerly, creative compulsion that touches every one of us. In its longer forms, it demands attention. In its chats, it (often) creates community. But even as I write this, my analog datebook/journal is sitting to my right along with a phases-of-the-moon calendar that was a gift from Katherine May, my late father-in-law’s 1950s Swingline stapler, and a box of Blackwing pencils. The words I read here compel me to pick up the printed books written by these Substackers. And then when I get them, I sit down on the couch and read them.

On actual paper.

But I can’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. We do not live in a binary world of this is good/this is bad, and when we try to, things go horribly wrong (clearly). But I have said goodbye to my Google and Apple calendars and have reverted to a nice re-fillable one made in Vienna. I wear an Apple watch because my mother is eighty-nine and still lives by herself, and I need to know if she or her personal aide or her doctor is calling me with an emergency, whether I’m on a walk with the dog or on a hike. (She did manage to call me eight times during my first Permission book event at Brookline Booksmith, so there are downsides.) But honestly? I’d rather wear this.

I remember an episode of Portlandia many years ago where a woman arrived at a hotel in the city (The Ace, or, in the show, The Deuce) and they gave her a turntable and some vinyl upon checking in. The woman who Susan bought her first house from used to knit sweaters from her Golden Retriever’s sheddings. So analog living definitely attracts parody. But at the end of the day, it feels less to me about trend or romanticism or being a Luddite than it is about recognizing chronic overload and its sisters, isolation and disconnection, and wanting to step off the conveyor belt of modern, corporative existence. A digital tracker does not need to know my every-minute whereabouts and buying habits. Beyond that, I don’t want to be distracted by a constant influx of information that The Great and Powerful Oz seems to think I want before I’ve even had a chance to consider it.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poor Man's Feast to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.