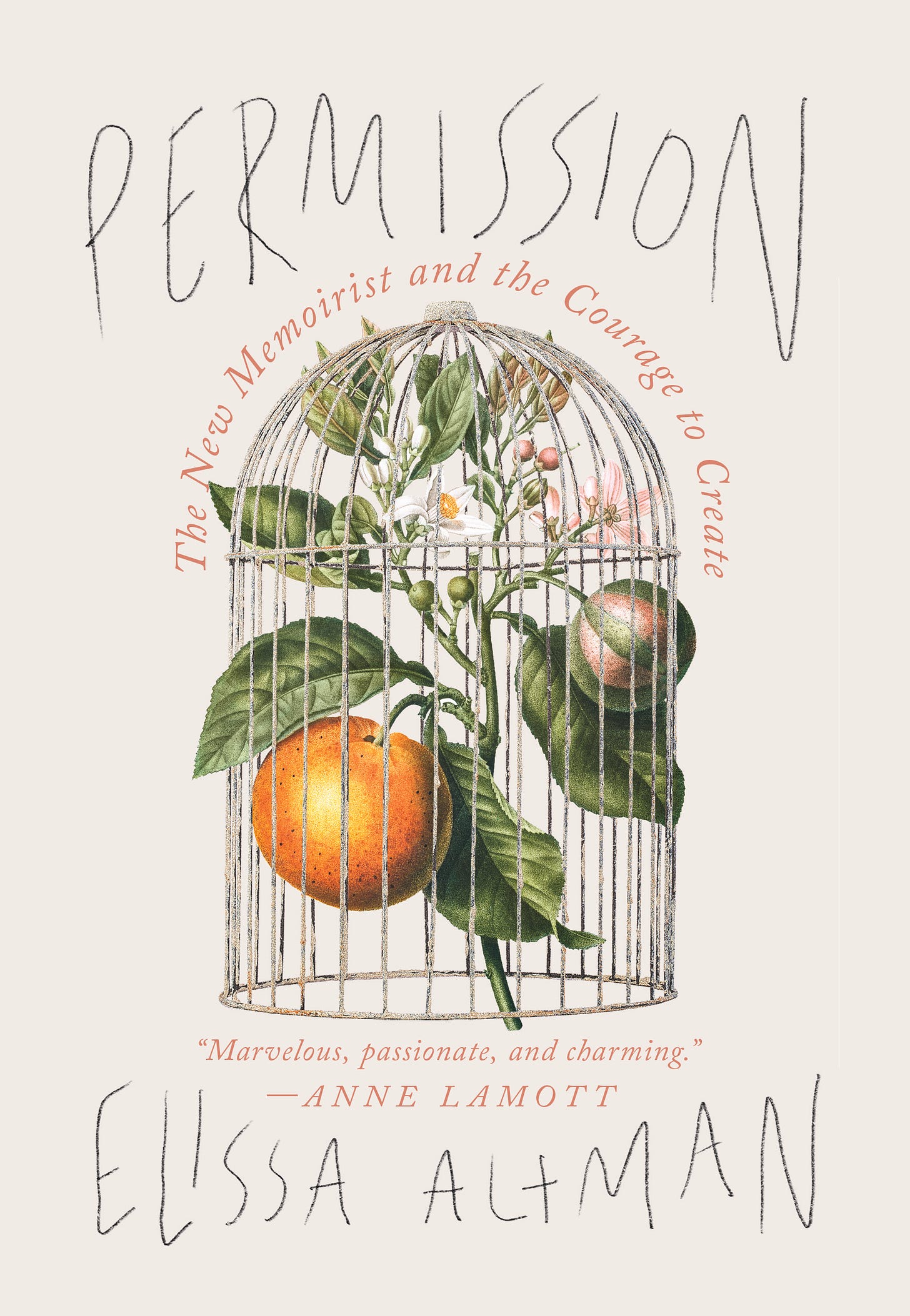

I have lifted the paywall on this piece, to mark the publication of Permission: The New Memoirist and the Courage to Create tomorrow. I will be in Brookline tomorrow evening, in conversation with Joanna Rakoff, and if you’re in the Boston area, please come and join us at Brookline Booksmith.

Tonight, I am sharing some thoughts on the memoir-writing process that come out of the many (many) questions I’ve received over the years from writers new and seasoned. These are all jumping-off points meant for discussion, rather than binary rules of the road; they are not excerpts (although I did release an excerpt for paid subscribers here.) I will never say Do this and this and this. I will always say Take into consideration this and this and this. Because each of us is in a different place in the writing process and in our lives, and what might work for you might not work for someone else.

Do I have to show other people my work before publishing it?

No. But you do have to think about it, and think about it seriously.

Ask yourself questions about intent and motivation: are you hoping to get someone’s approval or blessing? Are you trying to corroborate a story, to make sure you got everything right? Is the reason passive-aggressive? Is it an ethical issue?

To be sure: sometimes you will want to share it but most times you won’t, and unless a publisher’s legal department tells you that you have no choice (and all publishers are different), then you do have a choice.

There are no absolutes here. The rules surrounding writing memoir (or personal essay, or even fiction, for that matter) are not binary, meaning they are not black and white. They are different for every writer, and every book. Scroll up to the headline at the top of this post: the key words are HAVE TO. You do not have to. You can also never predict or control what someone’s response to your work will be, even if you do choose to show it to them. Your Aunt Sally may have a shocking response to a description of the way you water your houseplants, and demand that you remove it. Your ex-roommate from thirty years ago may be irate over your description of her mother’s red velvet cake which, once sliced into, resembled a bloodletting. You can never know for sure.

Every one of us is chipped, broken, damaged, beautiful, and imperfectly human.

There are some writers and teachers of writing who will loudly disagree with me about the need to show your work to people who appear in it, and that is fine. One writer/teacher I know — a brilliant woman who writes brilliant things — insists that it is an ethical issue, and she is not wrong about that. If your life has been touched by the doings of someone else (and it has because if you are reading this, you are presumably not living in a cave or a nunnery), it is imperative that you consider the question: should I let this person know what I’ve written about them/us? Should I show them how I have made them appear on the page? No one can answer that question but you. If you are publicly calling someone a snake, a destroyer of lives, a thief, or a moral miscreant, things will get complicated. Take, for example, the case of Nora Ephron writing about her ex-husband, the journalist Carl Bernstein, who famously had an affair while Ephron was four thousand months pregnant with their second son. Ephron fictionalized the story in her novel, Heartburn; Bernstein threatened to sue. Mike Nichols, a friend of both parties, made the movie of the same name, which was widely criticized, mostly by men, as being sour grapes. And Bernstein had the right, as part of the divorce agreement, to read the screenplay and drafts.

But here’s the thing: if you are a journalist in the public eye who has broken the Watergate case and you’re married to a brilliant writer who is also in the public eye, and you have an affair while your wife is schlepping around, massively pregnant with your second child, you can be sure: she’s going to write about it. Not that this kind of thing doesn’t happen all the time; it does. It also falls into Anne Lamott’s category of If you wanted people to write kindly about you, you should have behaved better.

Sometimes, showing a manuscript or a galley to a person or people who appear in your story won’t make a difference: when Honor Moore, author of The Bishop’s Daughter, wrote about her late father, Bishop Paul Moore, and his bisexuality — a fact that he eluded to in his own memoir before leaving his papers to his writer daughter — she gave each of her eight siblings a copy of the galley to vet. They all signed off on it, with minimal changes. When the book came out — and even though they’d seen it — three of them wrote a now-famous scathing letter to the editor of The New Yorker about their sister and the book. I’m of two minds: had she not shared the galley with her siblings, I would understand their response. But she did, they had an opportunity to voice their concern and ask for changes, they (largely) didn’t, and still pilloried her publicly when the book came out.

We all move through life with a finely honed veneer, and when someone else writes about us, that veneer we’ve carefully perfected crazes like porcelain.

Writing in the most loving way about someone won’t let you off the hook, either. Imagine this: You have gone to great lengths to show a person’s decency, their empathy, their kindness, their humor, their love, their sense of fairness. The book comes out and you get a cold shoulder from them because you didn’t write kindly enough about them, or, in their estimation, you got the story all wrong. They’re furious because you have left out something they feel is key to their story.

But it’s not their story. It’s your story.

Every single one of us views the world and our experiences in it through a filter of our own making, which is why you can put five adult siblings around a table and say Do you remember that time Dad got drunk on the Jim Beam at Christmas in 1975, and you will get five different versions, including Dad didn’t drink. Every one of those truths is valid, even though there can be only one empirical fact. The concept of narrative filter is a hard one to swallow because humans are heavily invested in being right. (You might have noticed this.) I once had a beloved family member comment on a story I was telling about something that happened to me when I was a teenager, when only my father and I were present.

That’s not the way it happened — she said, insisting that she was right, and absolutely indignant when I told her she wasn’t, despite the fact that she wasn’t even there.

I once heard this from Dani Shapiro: Nobody ever says Yay! There’s a memoirist in the family. She’s right. Mention at Christmas that you’re writing a memoir and soup spoons will drop. People will start to cough. Chairs will begin to move away from the table. Because no one likes being written about, positively or (certainly) negatively because it takes the control out of one’s hands. We all move through life with a finely honed veneer — a metaphysical selfie, if you will — and when someone else writes about us, that veneer we’ve carefully perfected crazes like porcelain. Every one of us is chipped, broken, damaged, beautiful, and imperfectly human. And for these truths to work in narrative, we have to remember Vivian Gornick’s words in The Situation and the Story: For the drama to deepen we need to see the loneliness of the monster, and the cunning of the innocent.

If you feel that you must show your work to someone who appears in it, start with an inquiry:

Am I trying to corroborate days/dates/places/other facts? Bear in mind that you actually might have a better memory than the person you’re asking. If you disagree with what they tell you, how will they respond? Also, do know that you will get reactions to other issues, whether you request them or not, as in I also think you should [fill in the blank]. Remember Mary Karr’s words: memoir is an act of memory, not history. (See my story of the siblings around the table, above.) It is important to honor your memory as your truth, seen through the filter of your experience. Exceptions: when you are relating a story that does not directly involve you but shines light on a point you are trying to make. When I recalled hearing, third-hand, that the novelist Kathryn Harrison wrote part of her first novel in her car while driving to Maine with her family, I couldn’t date the story nor could I claim that it was accurate, because I didn’t know the source. I wrote to Kathryn and asked her directly whether or not it was true. She confirmed it. If she hadn’t, I’d have taken it out of the manuscript.

Am I seeking approval or a blessing? I will be wrestled to the ground for saying this: you will rarely gain approval by showing your work to the people who are in it. They may love it or at least really like it, and their words will inevitably be followed by BUT. Their assumption — and this is the narcissism of human nature — is that if they appear in your book, it is about them. But it’s not; it’s about you. When I told my mother that I was writing Motherland, she was supportive, but she also trolled every bookstore in the city of New York, calling it The Book Of Me. During the writing process, she called almost every afternoon and said I have a story for the book; get a pen. I did not show the manuscript or the galley to her because she went into it believing that I was writing her biography.

Am I wanting to passive-aggressively show someone exactly what I feel about them? A bad idea; just don’t do it. Don’t write to exact revenge, either.

Will I show it to anyone, or will I keep it completely under wraps until publication? I firmly believe that every writer should have a trusted reader with whom they can share their manuscript — someone who is familiar with the story, who might be in the story, and who can guide them if/when they get off track. My first reader is my wife, who figures heavily in almost all of my work, and who is a voracious reader with an unshakable sense of fairness. She has saved me from myself on more than one occasion and, I suspect, will continue to.

A cardinal rule that Dorothy Allison once shared with me at a writer’s workshop (I am paraphrasing here): There can be no victimhood on the part of the writer. You have to write yourself as fucked up and shameful as your characters might be.

Whether you choose to show the people who appear in your work the manuscript (not a great idea) or a galley (a better idea), do remember: you have a choice. There are no hard and fast rules (unless your publisher says there are). Make this decision carefully, and on a case-by-case basis. Be kind to yourself; be safe. Do not feel obligated to share with your personal monster the words you wrote about him/her regarding their bilious behavior. You might nevertheless want to, but you do not have to.

The writing of memoir is like trying to walk a tightrope while wearing ice skates. It is a complicated, delicate business, and no two memoirs are the same. The best you can hope for is an offering of creative generosity and clarity, not only to the story and the people in it, but to yourself.

I absolutely get that you must show "loneliness of the monster, and the cunning of the innocent". But what if you were a child at the time the story took place? What if everything was outside your control and you were quite innocent? ASKING FOR A FRIEND

As someone who will be approaching this juncture sooner rather than later, I appreciate every bit of this, Elissa. Such valuable nuggets. Hope book tour is proving to be rewarding.