I couldn't peel it; my hands shook.

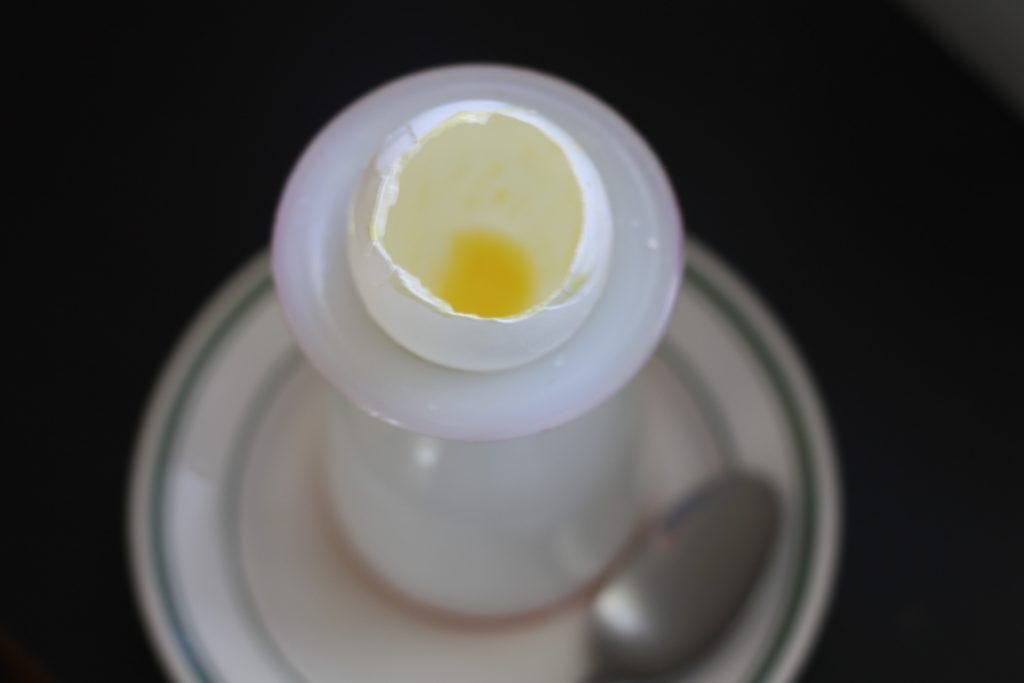

I ran them under cool water and dried them on my favorite linen towel hanging off the oven door handle --- the one that I never use, that I'm afraid to stain lest it cease being the new, fresh, perfect Fog Linen towel that it is. Still, my hands trembled, and when I tried to peel the morning's freshly boiled egg, I failed. I brushed the shell away with my thumbs to coax it off like my grandmother used to do when she made eggs for me in the chipped black and white enamel saucepan of my childhood. Instead, I gouged it violently, my thumb piercing straight through membrane, glair, crumbling orange yolk with its halo of overcooked green, until all that was left of the egg was the suggestion of sustenance.

My throat tightened. I fought back tears, and laughed at the utter ridiculousness of it: to cry over a mangled egg is inane and emotionally frivolous. Boiling an egg on this particular morning during this particular winter was all I could possibly manage, and I couldn't even manage that.

We call one another good eggs, tough or rotten eggs....We walk on eggs to spare fragile egos....We find the bestowal of an egg to be expressive of wildly divergent emotions: handed over graciously it betokens favor; delivered at high velocity it plainly indicates disgust, said Robert Farrar Capon. I add to this the egg's subtext of Life, cap L, and hope: in The English Patient, when David Caravaggio, erstwhile spy and thumbless thief, produces a single, purloined fresh egg for Hana, it means that the war is nearly over. When he drops it and it splatters at his feet, we know that the war will continue, however briefly, and more will die.

I grew up having an egg every morning of my life.

My father and I sat side-by-side at our Danish modern kitchen counter in Forest Hills, our backs to the Chambers stove where my mother silently soft-boiled two of them for three minutes, cracked them over slices of cold diet white bread stuffed like cotton balls into two brown melamine egg cups, and set them down in front of us. Years later, in the egg white omelety 1980s, I began to curtail my egg intake because of the genetically high cholesterol I was gifted from my mother. In the 90s, I discovered oeufs en meurette at the defunct La Goulue in Manhattan, and would have them once a year when I took my mother to her favorite restaurant for Mother's Day. In the early 2000s, I married Susan, who taught me how to make a meal out of a perfectly poached egg on garlic-rubbed sourdough toast drizzled with olive oil; we ate this at least once or twice a month. In the mid-early-2000s, when I began to write full time from home and was blessed with a chicken-keeping neighbor, I started making a single boiled egg every morning: I would sprinkle it with sea salt, roll it around in a shallow stoneware dish of dukkah, and eat it standing up in the kitchen, the dog at my feet. And then, like clockwork, my mother would call.

I can't talk, I'd say. I'm having breakfast. I'll call you back.

What are you having? she'd ask.

An egg, I'd say, my mouth full.

I'll stay on the phone with you while you eat, she'd say. I'll do the talking.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poor Man's Feast to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.