It was something I could never understand:

How a meal could be comprised of anything other than large plates, and two or three courses. I was raised this way: every night, when my parents, grandmother, and I gathered for supper, we sat down to 1) half a grapefruit, sprinkled with sugar and run under the broiler; 2) a piece of fish, or chicken, or beef, usually broiled (unless it was wintertime, and then the beef was stewed); 3) a slice of Entenmann’s pound cake, or a donut, or some apple strudel. If it was a particularly important dinner, my mother would douse lamb rib chops with vegetable oil, shove them under the broiler, and walk away; this always resulted in a my grandmother beating at the flames with a greasy flowered kitchen towel as they licked up the front of the oven door while the dog and I cowered in my bedroom.

It takes time to undo this belief, that a meal must always be three courses and comprised of big versus small, too much versus too little. Even now, when we see those stunning, well-styled photos of dinner parties and brunches, and tables creaking under the weight of the meal — glasses empty, bottles empty, plates showing broad stripes of blueberry pie filling or bits of ham, cubes of tofu and the remnants of kimchee, leftover salad greens wilting next to shrimp peelings — the implication is almost always that the meal has had many courses, and that somewhere in the background there are guests overstuffed and groaning with feelings of extreme bloat.

I eventually drew the line in the sand at Richard Olney’s directions for boning out and stuffing a whole chicken, the last line of which was Your chicken should now be turned inside out.

I remember years ago — many years ago — when I had become a full-fledged devotee of Alice Waters and Chez Panisse, and the idea of seasonal eating; I read her books cover to cover, and then Elizabeth David’s, Paul Bertolli’s, Deborah Madison’s, Paula Wolfert’s, Viana La Place’s. I dragged Judy Rodgers’ Zuni Cafe Cookbook to bed with me and vowed, back in my publishing days, to reissue the book’s seminal introduction as a standalone publication, bound like a bible between two semi-soft flexibind covers. I eventually drew the line in the sand at Richard Olney’s directions for boning out and stuffing a whole chicken, the last line of which was Your chicken should now be turned inside out.

These are the books that are still on my shelves, and the ones that I continue to turn to — they’re the ones that taught me to think about food differently, as a manifestation of flavor and anthropology rather than simply trend, or fuel. For the most part, though, I turn to them not for inspiration to cook massive meals: I now just stop short at the smaller plates, and I don’t go beyond them. I don’t want to eat big anymore: my body can’t cope with it, and I hate feeling constitutionally overwhelmed. I remember years ago, the first time I was in New Mexico for an Edible Communities conference, and Susan and I were staying overnight at Los Poblanos before flying back east. The hotel had just re-opened, but the kitchen was not yet operational. We’d spent the afternoon hanging around with Deborah Madison and her husband in their Galisteo home, and when it was time to leave, she handed us a small brown paper bag and explained that it would be our dinner since there was no food to be had at the hotel yet. We thanked her and left, and when we arrived at Los Poblanos, we spread out a napkin on the coffee table in our suite, and opened the paper bag: Deborah had packed us slender wedges of a caramelized onion frittata she’d made that day, along with some fruit, olives, and a little cheese. We didn’t need or want anything more. It was one of the best, most sustaining meals I’ve ever had, before or since.

I don’t want to eat big anymore: my body can’t cope with it, and I hate feeling constitutionally overwhelmed.

The inclination to eat more heavily exists, of course, in the cold weather months, and I think this is normal human biology at work. We gain weight in the winter months for a reason: because we’re mammals. But in the summer, my idea of sustenance changes. As I write this, we’re heading into Memorial Day weekend, where most Americans gorge themselves on the summer barbecue foods that we’re known for: the burgers and the hot dogs, the cole slaw and the potato salad and the ice cream. I’m not ever one to shirk off the responsibilities of traditional holiday cooking, and late last night, I decided that this Sunday, I’d make a platter of cold buttermilk-brined fried chicken for our neighbors. Susan will make her grandmother’s German potato salad. We’ll have some ice-cold beers and sit on the front porch; there may be some ice cream involved. And we’ll listen to some music and give thanks for each other.

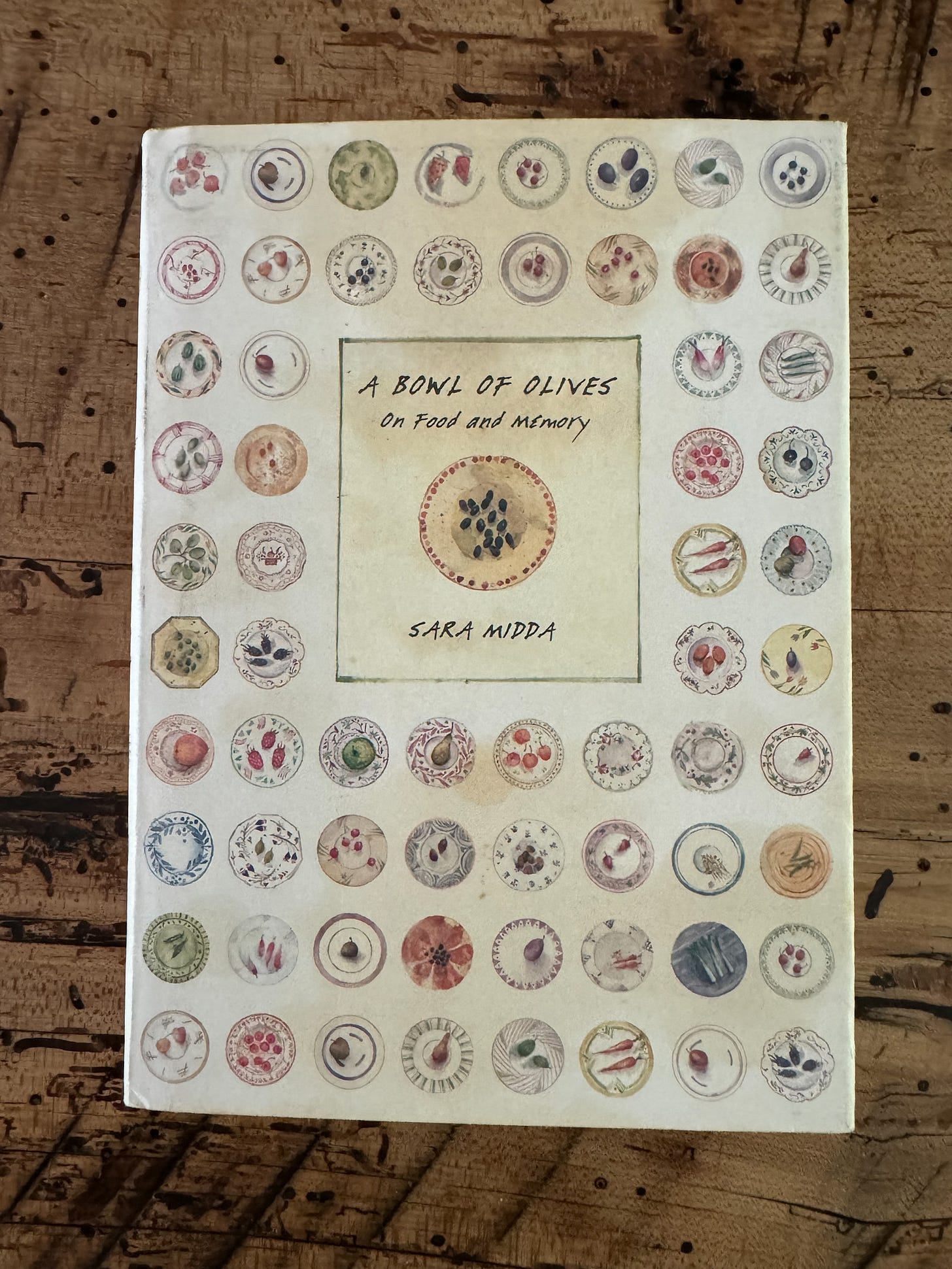

One of my favorite books for eating small came to me at a local book sale, and I treasure it: A Bowl of Olives: On Food and Memory by Sara Midda. Midda is a well-known designer and watercolorist, and her books are lovely. But this particular one struck me years ago because it was a visual confirmation of everything I had come to know as true about thinking of food and sustenance, especially in the warmer months. I’ve made many meals from bowls of warm olives and bread, or cold roast chicken and aioli, or warm figs stuffed with goat cheese, or toasted almonds and herbs, or slices of cucumber and red onion with chilies, lemon juice, and olive oil because of this slender little volume. And in the summertime, I don’t want anything bigger, or more.

It is true: I think that it’s human nature for our eyes to be bigger than our bellies. If we can manage to somehow snip that connection, to override it and think instead of how little we actually need providing it’s flavorful and delicious, we’d be better off for it. I remind myself of this fact every summer when I set out a small bowl of warm olives and a few slices of cheese, and call it dinner.

Warm Fragrant Olives

A great way to use the container of olives that might be lurking in the back of your refrigerator. I prefer using small Picholine olives for this dish but have successfully made them with Cerignola, Castelvetrano, or any combination. If they’re un-pitted, all the better.

1 tablespoon extra virgin olive oil

1 teaspoon cumin seeds, smashed once in a mortar and pestle

2 large cloves garlic, peeled and smashed with the flat of a knife

1 pinch red pepper flakes, or 1 small dried hot red pepper

zest from 1 lemon, in long strips (rather than gratings)

1 cup unpitted green olives, preferably Picholine, Cerignola, Castelvetrano, or a combination

juice from half a lemon

In a medium, heavyweight iron or French steel skillet (I love my Netherton Foundry prospector pan for this, and have also used an old French steel skillet), gently warm the olive oil until fragrant. Add the cumin seeds to the pan, and continue to warm, taking care not to let the cumin or the oil burn or overheat.

Add the garlic, the pepper flakes, and the lemon zest, and continue to warm for a minute or so. Add the olives and stir so that they’re coated with the fragrant aromatics. Continue to warm for about five minutes.

Leave to cool in the skillet, and then scrape out into a small bowl. Squeeze the lemon over the olives, give everything a quick stir, and serve with hunks of good bread.

I absolutely love everything about this wonderful post.

I too, love eating small bits of this and that, and have since I was a kid.

My mum, the chief cook in our house growing up, would occasionally get sick of it, and on Friday nights, before the weekly Saturday morning grocery shop, she put out a “clean out the fridge” dinner (what we now call, far more charitably, cheese and charcuterie). Bits of pickle and olive, leftover cheddar, a few slices of kielbasa and salami. Some crackers.

My sister and I would play in the backyard and occasionally run back for a handful of something in between somersaults, my parents would chat and snack on the balcony. We loved those dinners.

I'm not surprised that we repeatedly turn to the same books and that I also view the Zuni Cafe introduction as required reading for all cooks.

Thank you for this. Its exactly what I needed to read today to center and calm me.