“This is a place where grandmothers hold babies on their laps under the stars and whisper in their ears that the lights in the sky are holes in the floor of heaven.” - Rick Bragg

I am the daughter of a Naval aviator who landed his little unlit Grumman Hellcat F6F on an unlit aircraft carrier in the middle of the Pacific, at night, during the Second World War, using celestial navigation. And I was lost in Texas. I was so lost in Texas that I instinctively tilted my head back the way you do during dental surgery, and I looked up. It is in my DNA: I saw my father do this routinely when he was lost in the days before GPS. If he could see the stars, and if he could see the moon, he knew where he was.

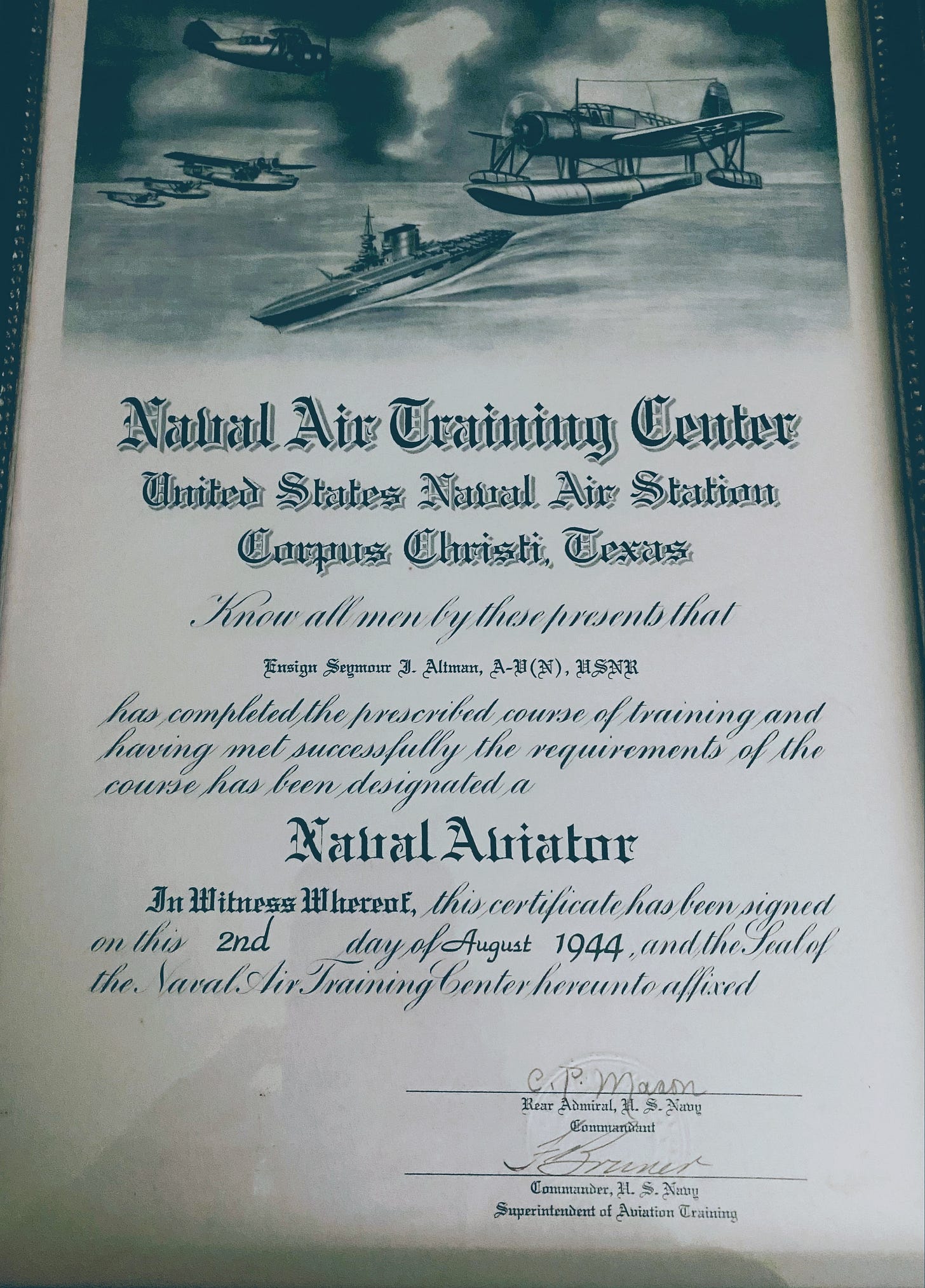

In my studio at home in Connecticut, I have my father’s Naval certificate framed and hanging over the shelves that hold my most important and sustaining books: the Renkl and the Kenyon, the Kimmerer and the Lopez and the Williams, the Beard and the Lamott and the May. I found the certificate in his files on a hot August day in 2002, between the time of his car accident and his death exactly a week later. Planning his funeral while he was still alive was excruciating, but one of the things that did not escape me was this: it was important for me to obtain a flag for his casket, in acknowledgement of his service as a nineteen year old night fighter pilot. While he was still alive, I had to provide the veteran’s administration with his honorable discharge papers in order to secure the flag, and I had no idea where they were or even what they looked like. So between morning and afternoon visits to the hospital to see him — I sat next to him, holding his hand, praying he would open his eyes — I spent hours sitting on the floor of his darkened study on Long Island with Susan, going through his files. And while I ultimately did find the honorable discharge papers, I also found the certificate that is now hanging on my studio wall, and that forever connects him, and therefore me, to Texas.

If you’re ever in Texas, make sure you have someone to share your barbecue with, because an ordinary dinner for one could feed a family of four.

My father, technically still a teenager, was stationed in Corpus Christi from 1943-44, when he received his wings. He lived there for months, became the editor of the Slipstream USNAS Yearbook, and embedded himself in place. He ate there, he caroused there, he fought there, often being taunted by men of lesser rank because he was Jewish and they’d never seen a Jew before. He spoke of it often, and told me to heed his words: if you’re ever in Texas, make sure to shake out your boots before you put them on, in case of scorpions. If you’re ever in Texas, make sure to pull back the covers on your bed before you climb in, in case of snakes. If you’re ever in Texas, make sure you have someone to share your barbecue with, because an ordinary dinner for one could feed a family of four. If you’re ever in Texas, remember: these people are poets. If you’re ever in Texas, remember: manners count for a lot.

My father was deeply compelled by Texas; he said it bit him like a snake — sank its teeth into him and refused to let go. It was unlike any other place in the world and almost impossible to describe succinctly because, in part, it is massive; it takes eleven hours to drive straight across the state from the Louisiana border to El Paso. It’s a complicated place with a complicated history and a complicated people, and it’s hard to get one’s arms around it; it’s easy to stereotype which is not only unfair — it’s wrong.

There is dust and highway and Waffle House and bluebonnets as far as the eye can see. And there is sky forever and there is, it seems, room for every thing and every one, and every conceivable, possible way of living.

I made it to Texas twenty-one years after I lost my father, after those terrible, endless days of sitting and waiting and then getting on my hands and knees searching for evidence that might afford him a last respect by the country he served. As I flew out to my writer’s residency in Corsicana, midway between Dallas and Waco, at the beginning of April, I was desperate to speak to him, to let him know where I was going, and that I’d keep his instructions — boots, bedclothes, barbecue, poets, manners — in mind.

In Rebecca Solnit’s introduction to Barry Lopez’s Embrace Fearlessly the Burning World, Solnit writes about the act of paying attention as entering a state of concentration, of focus, a state of being open to epiphany and rapture and communion. She writes

You arrive at a place, then you arrive at an awareness, then perhaps arrive at an understanding, which opens up the world to you and opens you up to the world. Finally, perhaps, you arrive at a relationship.

When I arrived in Dallas and made the fifty mile drive south to Corsicana with the residency director, Kyle Hobratschk, I looked: when you leave this glass and chrome modern city and begin to creep out beyond the plaited highways and the construction and the new buildings, the landscape begins to flatten out, and the bluebonnets explode from the medians, the clouds hang so low that they beg to be touched, and the signage begins to change. Everything about Texas is a dichotomy, a glaring and stunning contradiction: highway billboards placed by right-to-life activists are positioned directly above billboards advertising gun shops. Slick-haired lawyers whose faces appear to be two stories tall promise fair representation and directly face billboards for sex clubs, which are perched next to signs for mega churches. There is dust and highway and Waffle House and bluebonnets as far as the eye can see. And there is sky forever and there is, it seems, room for every thing and every one, and every conceivable, possible way of living.

I arrived intending to complete the first draft of my next book; the location of my residency space was on the third floor of the late Victorian brick 1890 Oddfellow’s Hall now called, simply, 100 West, which denotes its location: 100 West Third Avenue, Corsicana. Next door, an auto body shop; across the street, studios belonging to residency director Kyle Hobratschk, who founded the residency while still in his early twenties and a recent graduate from SMU, and essayist David Searcy, and David’s wife, artist Nancy Rebal. Around the corner and a few blocks away: Storefront, the residency’s small bookshop and presentation space. Down the main drag, the retro shop with the old guitars in the window, and the proprietor who told me she now keeps turtles at home because she forgot to clean her swimming pool. Downstairs and around the corner, Cocina Azteca, the proprietors of which fed me the best gorditas I have and probably will ever eat in this lifetime, and where, one night after I finished teaching my weekly masterclass, a large German shepherd appeared out of nowhere from the alley behind the restaurant, head-butted a white styrofoam takeout container in my left hand which sent my huarache leftovers flying through the air, leaving me with an empty container still in my left hand while he ate my next day’s breakfast, wagging the whole time. A week later, the restaurant/dog owner insisted on comping my mole enchilada.

It was hard to concentrate while I was at 100 West; there was a high vibration, a hum, a full moon, an eclipse which made my hands shake. I was surrounded by brilliant visual artists and writers. And there was too much to look at, to feel, to touch. It’s a tactile place, and I found myself running my hands along the walls and the door trim at 100 West, much of which shows its age in layers, like tree rings; everything in the building is entirely original with the exception of the kitchen countertops. I began avoiding mirrors early on because I always expected something or someone to be staring back at me from over my shoulder: I learned, at some point, that the second floor of 100 West had, at one time, been used as a meeting place for the Ku Klux Klan and the Orthodox Jewish community in Corsicana, which compelled me, on Passover, to say a quiet prayer for these people from another time and place who had come to the town as merchants and dry goods salesmen with their families, settled for a while, and moved on. I had questions: there is a well-known Reform synagogue in Corsicana, which has gone unused since 1980. Where there is a synagogue, there is usually a Jewish cemetery. I imagined making a short film: a middle aged lesbian writer borrows a car, maybe a light blue low-rider from the Reagan administration, asks directions to the Jewish cemetery but no one knows where it is; there’s no one left who can remember except for an older Mexican gentleman sitting on a stoop outside the auto body shop, and he takes her there, he insists on driving, and he waits from a distance while she places a small rock on each headstone as is tradition, to let the bleached old bones know: someone is still thinking of them.

It’s a tactile place, and I found myself running my hands along the walls and the door trim at 100 West, much of which shows its age in layers, like tree rings.

Corsicana undid me, and I am still trying to get my arms around this fact; I spoke one evening with the magnificent poet Alysia Nicole Harris, who now makes her home in this Texas town, and she agreed — it gets into your body at the cellular level. There’s an indescribable magnetic pull here, and what makes it such an ideal place for a residency be it for artists or writers: there is story everywhere, on every street, every empty storefront, in every abandoned lot, in every gorgeous 1920s home on Mill Place, built a short time after the town hired a water well driller who hit oil instead, and inadvertently started the first Texas oil boom in 1894 and a company called Magnolia Oil —Mobil — was born.

The act of paying attention is entering a state of concentration, of focus, a state of being open to epiphany and rapture and communion. And I found myself avoiding the mirrors of 100 West and stepping outside and tilting my head back the way I’d seen my aviator father do as he had been taught in Corpus Christi, and I found the moon hanging low over the town, and I knew exactly where I was.

You’ve captured the terrible beauty that is Texas; so much to admire and yet...

I’ve never read anyone with a greater gift for holding one’s attention!

Elissa, you are your Father’s daughter and Texas will always welcome you with open arms. Return soon and use the side door as you are now a part of the family.