Bits and pieces of our life together continue to show up everywhere, spontaneously and unannounced.

It's just not something you ever expect, is it, to blindly reach into a shoe box of ancient cancelled checks from long-defunct banks and small yellow canisters of old Super 8 film --- the things he inexplicably saved long after his marriage was over --- and pull out the only two remaining pieces from the 1950s chess set that you last saw sitting on your parents' Danish modern coffee table in 1973, when you were ten, and Nixon was in office. The rest of the set --- a black marble and white alabaster number that your father bought at that chess store down in Greenwich Village one night after hearing Coleman Hawkins play at the Village Gate --- is missing, and the things that he saved, that he carefully squirreled away and wrapped up in a fading shroud of worthless bank notes that tracked his every expenditure over the course of nearly two decades, were the King and Queen.

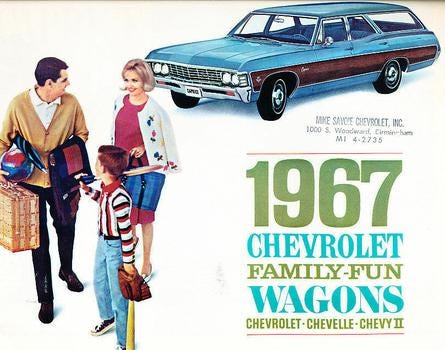

Like many people who became instant grown ups after coming home from The War, my father was a great believer in tradition: The 2.5 children, the dogs, the chicken in every pot, the vacations, the family dinners, the house in the suburbs, the sensible and clunky brown Mercedes sedan, and eventually, the station wagon. We never had the Mercedes --- just a dark green Chrysler Imperial that my mother set fire to one night in North Carolina when we were driving home from a trip to Florida. The day my father finally came home with a 1967 royal blue Chevy station wagon the length of a yacht, my mother took one look at it, gasped loudly, and said Take it back Cy, or I'm leaving you. She grabbed my four year old hand, turned around, and off we marched, back upstairs to our apartment.

The things in our house that spoke of family and togetherness and conviviality were his, not hers. There were the sets of early 1960s Arabica Ware, the fire engine red service for eight that a friend of his had brought back from Spain in the late 50s before he met my mother. There were old movie cameras and projectors and an enormous, collapsible metal screen, and reel-to-reel tape machines on which he'd record his young nieces singing children’s songs. On a low shelf in the bookcase in the living room, next to the stacks of Charlie Ventura, Yma Sumac, and Mohammed El-Bakkar albums there were two cookbooks: Craig Claiborne's New York Times Cookbook, and Dione Lucas's The Cordon Bleu Cookbook, both of which my father had bought for himself as a bachelor --- the former in 1962 right before he married my mother, and the latter, in 1948, before moving into his own apartment in Boston.

My father worshipped Dione, as he called her, like she'd been a personal friend. There were the odd accusations of frequent inebriation and general wackiness, but Lucas believed that the preparation of good food is merely another expression of art, one of the joys of civilized living, and my father agreed. Which is why it was apparently not unusual to find him standing in his bachelor kitchen on Commonwealth Avenue a few hours before a hot date, preparing Sole Veronique, which required the peeling of grapes and the manual dexterity of a brain surgeon.

If you can't bring yourself to peel a grape for the woman you're going to marry, something is wrong.

My father never prepared Sole Veronique for my mother when they were dating, which should have been a sign that they were doomed from the start. Because if you can't bring yourself to peel a grape for the woman you're going to marry, something is wrong. There were the silver tip roasts that my father eventually taught her how to make so that she could cook for him (bring the roast to room temperature, massage with salt and pepper and nothing else), along with the perfectly rolled omelettes and the foie de veau and the various fondues, and the Chicken Paprikash that the chef at the Csardas Restaurant gave him the recipe for after he pleaded like a baby.

But peeling grapes for my mother? I don’t think so.

Eventually, when my father moved out, he left behind the cookbooks, which I carried with me to college. But he took with him the Super 8 cameras and the projectors, the reel-to-reel tape recorders, the Arabica Ware and the plates, the Yma Sumac and Mohammed El-Bakkar albums, and the giant, collapsible screen, which now, twenty years after his death, sits in my basement covered in a thin rime of dust, in a tidy little suburban home that I'd like to think he would have loved; although we don't own a projector, I can't bring myself to give the thing up, or even to clean it off, in the same way that I can't part with the King and Queen, who now stand in my office on the windowsill looking away from each other, disconnected and confused.

Sole Veronique

From Delia Smith

Not quite Dione’s version, but everything that Delia Smith does is brilliant, so here we are.

2 good-sized Dover or lemon sole, each about 12-16 oz (350-450 g), skinned and filleted

3 oz (75 g) Muscat-type grapes

½ oz (10 g) butter, plus a little extra

1 heaped teaspoon chopped fresh tarragon

6 fl oz (175 ml) vermouth or dry white wine

½ oz (10 g) plain flour

5 fl oz (150 ml) whipping cream

salt and freshly milled black pepper

Peel the grapes well in advance by placing them in a bowl and pouring boiling water over them.

Leave them for 45 seconds, then drain off the water and you will find the skins will slip off easily. Cut the grapes in half, remove the seeds, then return them to the bowl and cover and chill in the refrigerator until needed. When you are ready to start cooking the fish, begin by warming the serving dish and have a sheet of foil ready. Then wipe each of the 4 sole fillets and divide each one in half lengthways by cutting along the natural line, so you now have 8 fillets. Season them and roll each one up as tightly as possible, keeping the skinned side on the inside and starting the roll at the narrow end. Next put a faint smear of butter on the base of a medium frying pan and arrange the sole fillets in it. Then sprinkle in the tarragon followed by the vermouth.

Now place the pan on a medium heat and bring it up to simmering point. Cover, then put a timer on and poach the fillets for 3-4 minutes, depending on their thickness. While the fish is poaching pre-heat the grill to its highest setting.

Meanwhile take a small saucepan, melt the butter in it, stir in the flour to make a smooth paste and let it cook gently, stirring all the time, until it has become a pale straw colour. When the fish is cooked transfer the fillets with a fish slice to the warmed dish, cover with foil and keep warm. Reserve the poaching liquid. Next boil the fish-poaching liquid in its pan until it has reduced to about a third of its original volume. Stir in the cream and let that come up to a gentle simmer, then gradually add this cream and liquid mixture to the flour and butter mixture in the small saucepan, whisking it in well until you have a thin, creamy sauce. Taste and season with salt and freshly milled black pepper.

Pour the sauce over the fish and pop it under the pre-heated grill (about 4 inches from the source of the heat) and leave it there for approximately 3 minutes, until it is glazed golden brown on top.

Serve each portion on to warmed serving plates, garnished with grapes.

Serves 2 as a main course, or 4 as a starter

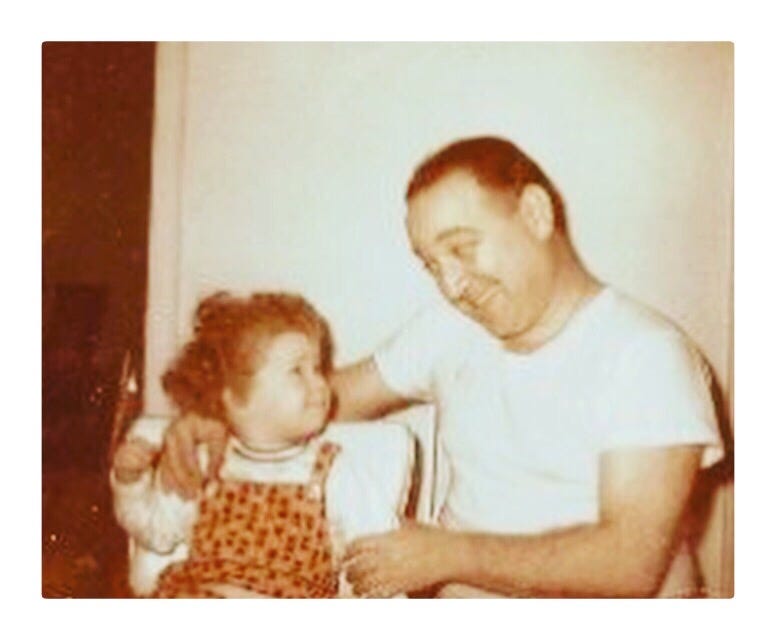

Oh. . .how. . . I have loved getting to know your father through your exquisite writing. I especially love him loving you in the photo. . .

Beautifully written and expressed, one could see she was her Daddy 's girl. Such love, so appropriate for Father's Day