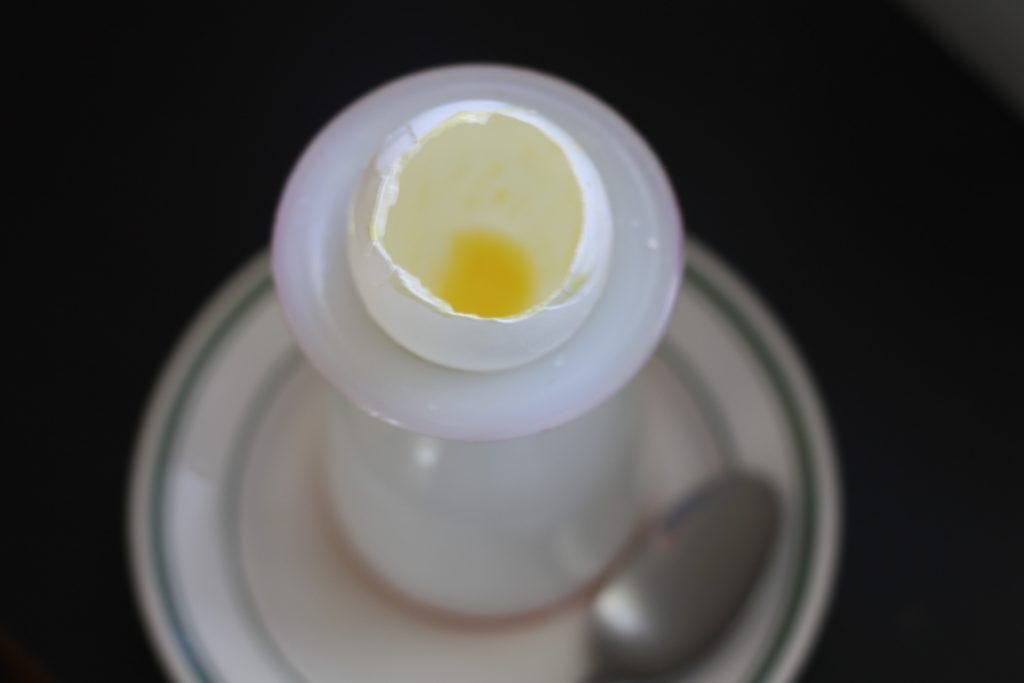

my mother's eggs

On Cooking Her Favorite Food

Every weekend, Susan and I travel down to the city to make decisions.

The hideous porcelain Italian figurine of a tennis player comes home with us for consignment. I plan to give an unworn ostrich, bamboo-handled purse to a writer friend who will love it. Susan, who is more careful than I am, bubble wraps my great-grandmother’s porcelain tea service from Austria; I’ll figure out where it will live in our house later. I leave behind the first cookbook ever given to me by a college friend with whom I no longer have a relationship, after she made it clear that she could be friends with me, but had no interest in my wife because she did not approve of us. (She, this friend, assumed that I somehow wouldn’t notice that every time I mentioned Susan’s name, she’d change the subject. Alas. Sorry to disappoint.) My father used to say that he divorced my mother because every meal she made was a sacrifice or a burnt offering, so I left the cookbook in my mother’s kitchen when I moved into my own apartment two years after college graduation. I hoped that she would crack it open one day and find some recipes she liked. Or maybe even just one.

This was a woman who called me on average ten times a day, every day, during the twenty-six years that Susan and I have been together; that’s 94,900 phone calls.

My mother has been gone since late October, and every day, grief jumps up and bites me in the rear when I least expect it. We were poster children for codependency; we gave Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds a run for their money. When someone asks me to distill our relationship, I make them watch Postcards from the Edge, and I take questions afterwards.

How could I not be overwhelmed with grief? This was a woman who called me on average ten times a day, every day, during the twenty-six years that Susan and I have been together; that’s 94,900 phone calls. We had a good-bad-loving-hating-wrathful-vengeful-joyous-affectionate-dispassionate-codependent-enraged-warm-emotionally violent relationship for most of my life. As anyone dragging their way through the mudpits of new and complicated grief will tell you, some days are good, and some days are like the dental chair scene in The Marathon Man.

Dismantling her apartment has been witheringly hard; at least once, I had to remove myself from her bedroom when I began to hyperventilate. My mother moved in in July 1981, shortly after marrying my stepfather; I was working as a lifeguard in upstate New York, and when I left for the summer, we were still living in Forest Hills, where I’d been raised for the first eighteen years of my life. When I returned home to pack for my freshman year at college, home was now a different apartment in a different borough, and the people who moved us while I was two hours away — namely, my grandmother and some of the factory guys from my stepfather’s fashion business — put the stuff of my childhood wherever they found room for it. Which means that I can be folding up an unworn Hermes scarf one minute, and blowing the dust off my disintegrating copy of Curious George the next. During our visit last week, I discovered that my mother had never gone through my beloved grandmother’s things when she died in 1982, and now I’m tasked with doing that as well. The part of the apartment I’m avoiding most, though, is the kitchen — specifically the kitchen drawer, where there exists, side by side, single pieces of black-handled Danish modern cutlery from my childhood, a box of unused Ginsu knives, a 1940s egg beater, a hard-boiled egg slicer, and an egg timer. My mother liked to cook eggs, and did so many times a day, for as long as I can remember. Breakfast, lunch, dinner. A midnight snack. Time never mattered.

As a child, I grew up having my mother’s eggs every day of my young life. My father and I sat side-by-side at our Danish modern kitchen counter in Forest Hills, our backs to the Chambers stove where my mother silently soft-boiled two of them for three minutes, cracked them over slices of cold diet white bread stuffed into two brown melamine egg cups, and set them down in front of us. In the heat of the summer, when she was loath to turn on the oven, she made us a lunch of what she called My French Omelette: four eggs beaten senseless, poured into a hot teflon pan greased with margarine, two slices of American cheese dropped end to end into the middle of it, the eggs folded over the cheese, and the whole thing (which by now had turned a russet brown) plated and served with ketchup. If hard-boiled eggs were on her mind, she’d barely cover them with water, crank up the heat so that the flames were licking up the sides of the small saucepan she’d cook them in, walk away and wait for them to explode, which meant they were done. When she fried eggs for breakfast, she never quite got the hang of flipping them, which meant that we always wound up with sunny-side up yolks with the consistency of a squash ball. Still, she declared them a perfect food, which, for the most part, they are, and — rubbery or not — I loved and love them as much as she did.

Years later, in the egg white omelety 1980s, I began to curtail my egg intake because of the genetically high cholesterol I was gifted from my mother. In the 90s, I discovered oeufs en meurette at the defunct La Goulue in Manhattan, and would have them once a year when I took my mother to her favorite restaurant for Mother's Day. In the early 2000s, I married Susan, who taught me how to make a meal out of a perfectly poached egg on garlic-rubbed sourdough toast drizzled with olive oil; we ate this at least once or twice a month. In the mid-2000s, when I began to write full-time from home and was blessed with a chicken-keeping neighbor, I started making a single boiled egg every morning: I would sprinkle it with sea salt, roll it around in a shallow stoneware dish of dukkah, and eat it standing up in the kitchen, the dog at my feet. And then my mother would call, like Pavlov.

I can't talk, I'd say. I'm having breakfast. I'll call you back.

What are you having? she'd ask.

An egg, I'd say, my mouth full.

Good girl, she’d say. I'll stay on the phone with you while you eat. I'll do the talking.

And she did: sometimes happy, sometimes angry, often raging against one person or another who had somehow done her wrong. There were laundry people who used the wrong detergent, cab drivers who took her the wrong way to her destination, makeup that she'd ordered that didn't arrive when she needed it, an accompanist who didn't return her call, the Jewish deli that forgot to remove the peas from her matzo ball soup. There were old friends of sixty years with whom she was engaged in constant battles, bus drivers who drove too slowly, bus drivers who drove too quickly, the cable company who was trying to bilk her, her long-deceased ex-husband --- my father --- who she was convinced was crazy, her second husband who didn't make provisions for her before he died of a cerebral hemorrhage, and Perry Mason, who she was completely in love with even though 1) he didn't actually exist in real life; 2) Raymond Burr was dead; and 3) when he wasn't dead, he was gay.

A pre-dawn text from the caregiver would come in first: She's calling you in five, she'd write. Just FYI.

It wouldn't matter to me if he was, she'd add. I coulda changed him.

I have to go, I'd say, wiping the dukkah crumbs from my mouth.

After her first catastrophic fall in December 2016 --- after the surgery and the rehab and the return to her home with a caregiver she hated --- her morning calls came earlier. A pre-dawn text from the caregiver would come in first: She's calling you in five, she'd write. Just FYI.

By January, cartons of eggs --- my neighbor's chicken eggs, a plastic tray of quail eggs, six duck eggs that I'd bought over the holidays as a treat --- began to pile up in my refrigerator, shoved into the back alongside half-empty jars of Hellman's mayonnaise and squashed tubes of anchovy paste; I lost track of them, and couldn't remember which eggs were old and which were fresh. While trying to navigate the world of being a care manager for a woman who could not be controlled, I often forgot to eat breakfast, and sometimes lunch. I'd look up from my computer at three o'clock, the sky outside my office beginning to change, and realize: I hadn't eaten anything all day. My skinny jeans began to hang off me.

You look terrific, my mother would say when I'd come to visit her every week. You have cheekbones again. Can I make you an egg?

How are you sustaining yourself, a concerned friend asked me. What's the easiest way for you?

Eggs, I told her. But I have no appetite.

Don't you understand, she said. Eggs are life. They are perfect. Boil one for yourself. Every morning. Even if you don't eat anything else until dinner, you'll be okay.

The next day, after Susan left for work and the dog had been walked, I took out the carton containing the ones from my neighbor; they were large, small, narrow (one of her girls laid eggs that were nearly flat), round. They were blue, green, and white. There were brown speckles on some, and bits of feather stuck to others.

I placed a small green one in my favorite ancient Le Creuset butter warmer. I filled it with water, put it on the stove, and when it boiled I covered it, removed it from the heat, and set the timer for eleven minutes. When the bell went off, I drained the pot, ran the egg under cool water until I could handle it, stood over the sink, and tried to gently peel it. The phone rang four times and stopped.

I cried at the absurdity of it: I was a food writer who couldn't even feed myself an egg, or provide myself with the most basic form of life-giving sustenance.

I peeled.

The phone rang again and stopped.

I peeled.