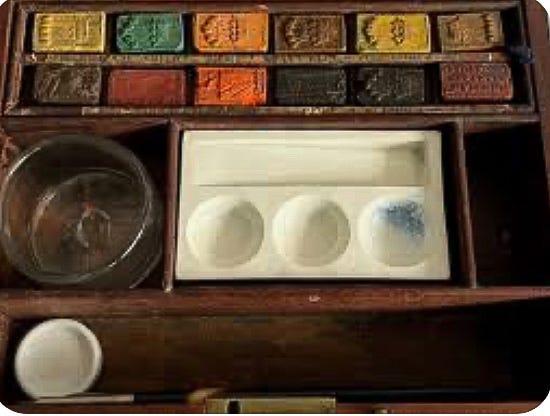

I am a fan of the British artist and writer, Jackie Morris, whose magnificent watercolor illustrations are so evocative —- imagine fox like a Zen ensō — that I find myself regularly going down rabbit holes to just gaze at her work (which includes The Lost Spells, The Lost Words, The Unwinding, and others that I love). But a few years ago, in the throes of lockdown, I found myself watching Morris do something I’d never seen done before: bring back to life antique watercolor paint blocks, some dating back centuries. Asleep for generations.

Not long ago, I wrote in this space about visiting an exhibit at the Yale Center for British Art, for which there was an audio component; I listened and heard a squadron of RAF pilots inadvertently flying over the field where the recording was being made, on their way to execute a bombing run on Nazi Germany. Listening was like reaching my hand through a scrim of time and space, and into another dimension. I’m fascinated by quantum physics and the sense that time as we know it is purely a human construct. In truth, I believe that times coils back on itself in a circular fashion. The great Rob Macfarlane speaks of traces — remnants of another time that exist in the present, linking the two:

We all carry trace fossils within us – the marks that the dead and the missed leave behind. Handwriting on an envelope; the wear on a wooden step left by footfall; the memory of a familiar gesture by someone gone, repeated so often it has worn its own groove in both air and mind: these are trace fossils too. Sometimes, in fact, all that is left behind by loss is trace – and sometimes empty volume can be easier to hold in the heart than presence itself.

When Jackie Morris breathed life back into watercolor blocks that had been asleep for centuries, I could not help but think: who had used them last? What had been painted? Had the American Civil War taken place yet? I think of time as a grand expanse that will not be corralled, but I also think of it in the sense of the mundane, and the manner in which it effects our day-to-day: the tools we use, the gifts we buy, the books we read, even the recipes we cook. The traces of our lives and the lives of others that cross years, decades, generations, centuries. In a world subsumed in this season by things for which time is both expandable and expendable (How long will it take before your child gets bored with shiny plastic object A; how long will the plastic/rubber kitchen tool you’re giving your sister-in-law sit in a land-fill?), and by single-use objects and trendy must-haves and desperately-needs beginning to grow dim long before the holiday is over, I find myself considering the issues of time and life of an object when choosing one to give as a gift, or to bring home for my own use.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poor Man's Feast to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.