Last August, my friend Simon sent me a box of his mother’s work.

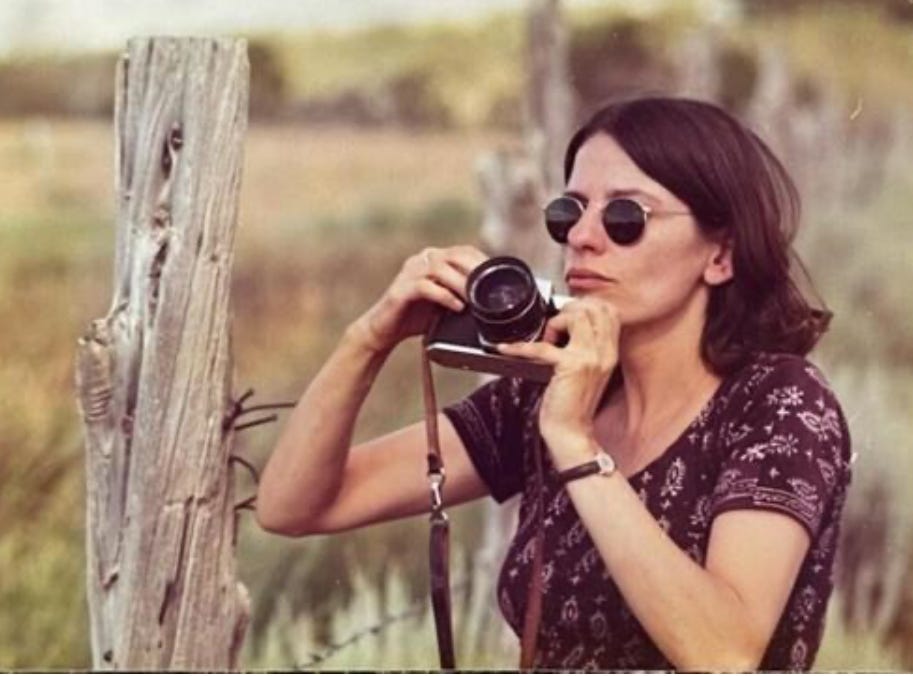

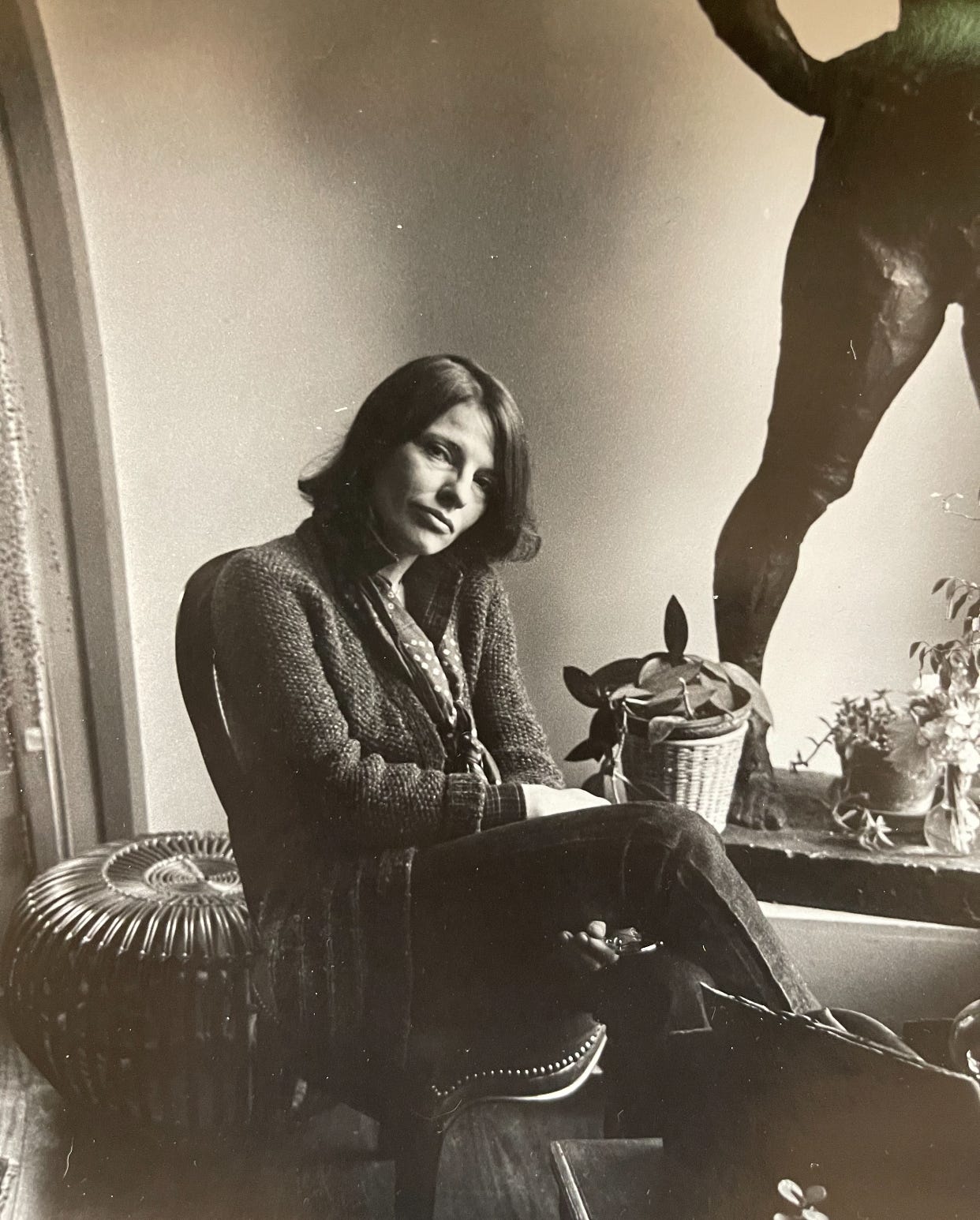

Sylvia de Swaan was dying, slowly, her body and mind disintegrating under the burden of a dementia and Alzheimers that she had managed to conceal well enough that they were probably far worse than anyone knew, early on. She had been a well-known visual artist — I knew her work long before her son became my friend, and I just never put two and two together — whose photography and visual narratives touched me ineffably.

When Simon told me he’d sent me a box of her work because he thought it would have meaning for me, he added that to keep the box’s contents from rattling around, he’d included one of his mother’s old woven woolen bags, acquired, presumably, when she lived in Mexico with Simon’s father, architect Salomon de Swaan. The bag was threadbare and worn, he said; he was unaware that I am a bag person, and also, a box person. Meaning: I collect physical containers and holders of experience and place, time and memory, and I always have, since I was a child. So as much value as I placed on the art contained in the priority mail box, I also placed on the bag itself.

Simon and I became friends in the way that often happens in the world of social media. The first time we spoke was when I was trying to unsuccessfully check into a Harlem hotel while on a 2016 book tour an hour or so before my event on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and I’d posted something on Facebook about not being able to do it. He sent me a private message, gave me his cell number, and asked how he could help: at the time, Simon was working in an executive role in the hospitality industry, and his offer of service was deeply generous, especially considering we’d never actually met. The reservation got sorted out, I checked in and did my event, and I never forgot his kindness. We began communicating regularly, our stories unfurling before us. In my books, I’d written bits and pieces about my extended family members and their history, and he shared his with me. We made the discovery that we both had direct ties to Czernowitz, Romania: my paternal grandmother was born there in 1898 and came with her family to America two years later, escaping Europe’s descent into darkness thirty-three years later. Simon’s mother, Sylvia, had been born in Czernowitz in 1941, lost her father to Russian army conscription (he was never heard from again), and spent the war with her mother and sister surviving forced labor in the Transistria ghetto.

And this is why the art of memory and witness is so vitally important: it prevents de-historicizing.

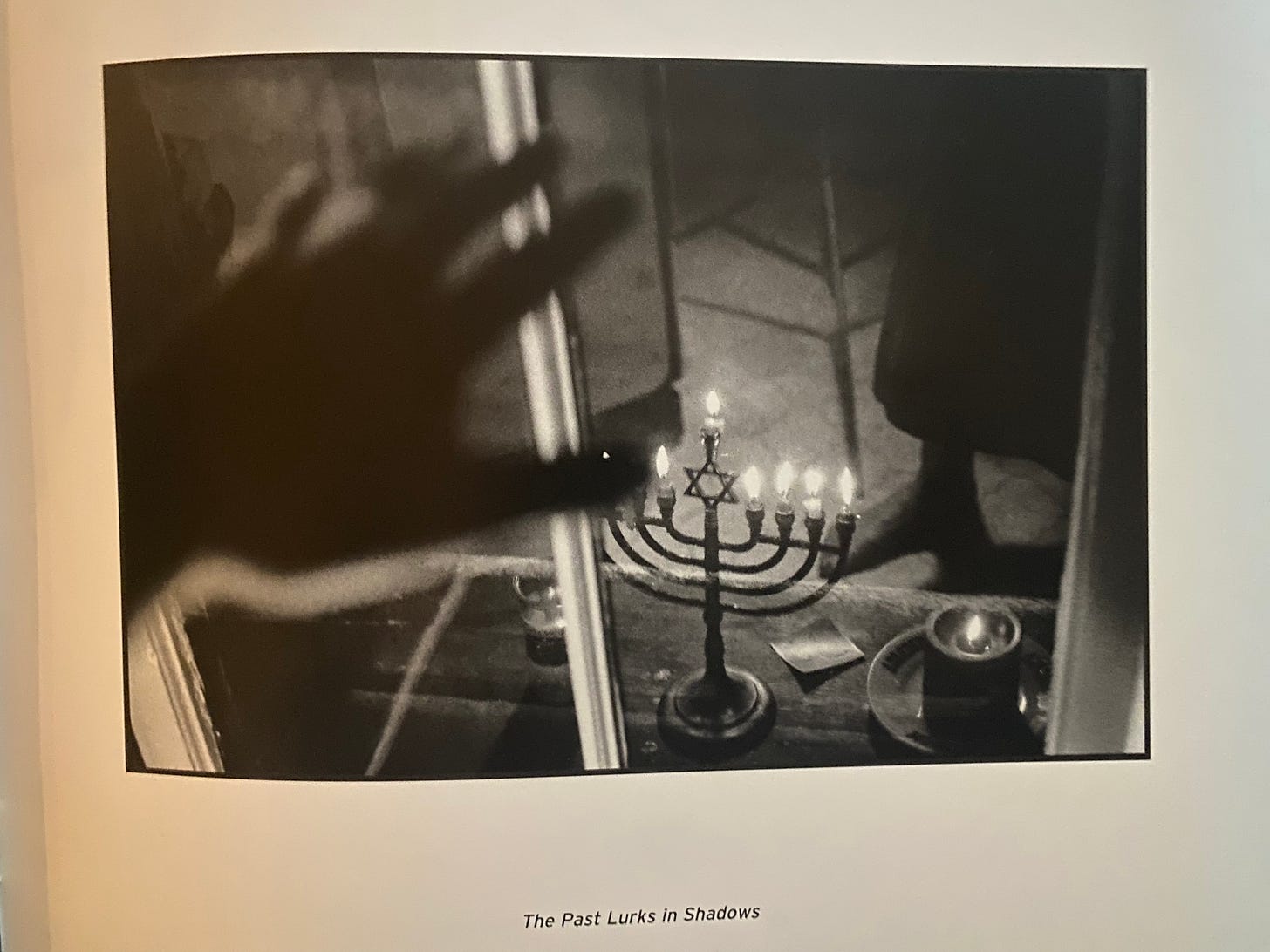

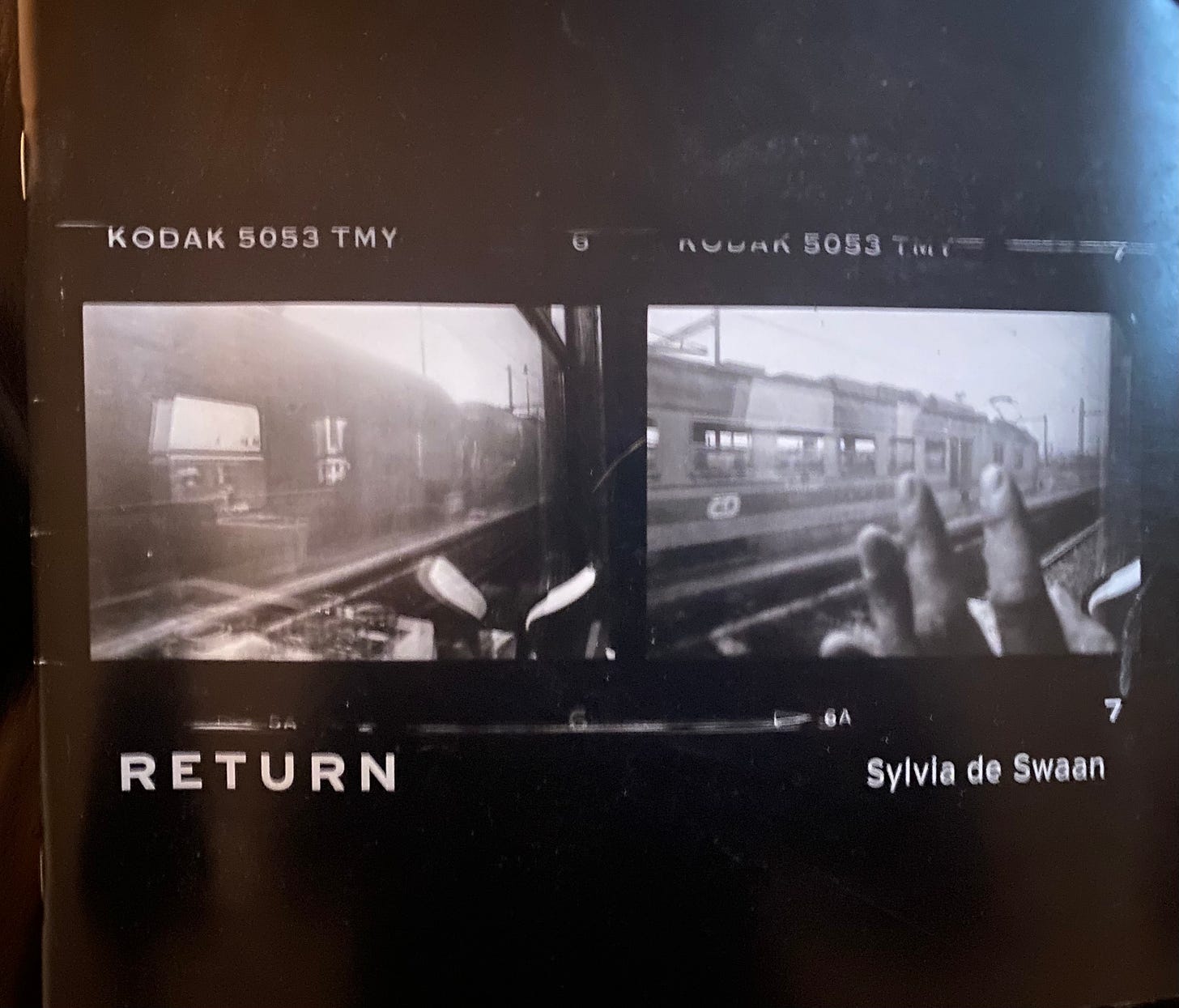

My grandmother found peace in music and art, and went on to be a classical pianist who performed Chopin at fourteen, in New York’s Town Hall. Simon’s mother, after living with her sister and mother for years in Displaced Person’s Camps in Germany, came to New York in 1951, enrolled in the High School of Music and Art, and began a life dedicated to photography, visual art, and storytelling. She eventually moved to Mexico City and lived there from 1962-1973 before moving with Simon to New Orleans and finally, to Utica, New York where she founded Sculpture Space and became an instructor at Hamilton College. In 1990, she returned to Czernowitz to understand who she was, her past, her roots. Upon her return to the States, she created Return: The Landscape of Memory, which she wrote

is about travel, individual and collective memory and identity; return to my roots, transience and loss, metaphor and flashbacks. It's about seeking symbolic ways to depict the bygone and the invisible; about telling open-ended stories that ask questions for which there are no easy answers.

Over the months since the arrival of Sylvia’s work in my home, I have taken my time going through it, as if each item contained in the box — the catalogues, the monographs — were thousands of pages long, and the bag itself heavy as a grain sack full of sand. I have long had a tendency to turn away from my own history and the possibilities and probabilities of life and fate, and what they mean when the world goes dark. It is too much for me to absorb, and I have a classic trauma response: I shut down. But a few weeks ago, when I came upon the invented word de-historicizing used in context to describe the re-writing of history as it has been known to this point, I found myself clinging to the idea of memory — not even my own memory or the memories of my family and people like my family, but human memory writ large, and what it means to re-write what one simply doesn’t like, or doesn’t accept, or doesn’t agree with. To create new truths and new facts that fit narratives designed to organize information in a specific and biased way to effect a particular end result. The de-historicizing of the Black experience in America might then include the well-known and utterly despicable myth of the happy slave. Likewise, the de-historicizing of the European Jewish experience includes Holocaust denial. The de-historicizing of the Palestinian experience includes myths revolving around Gazan history, which dates back thousands of years, as opposed to the middle of the twentieth century. The de-historicizing of the Israeli experience might include denial that the events of October 7th didn’t actually happen; many people —brilliant people for whom I have, or at least had profound respect—have told me that it didn’t.

When I unpacked the box that my friend Simon sent me and I pulled out Sylvia de Swaan’s little woven bag, I was taken by its patterning, its visual repetition. I know little about Mexican fiber arts beyond the fact that they are beautiful, ancient, and almost always represent a story, and this bag did just that: it was the same pattern, over and over and over. When I began to go through the catalogues and the monographs, the same was true: identical patterns, again and again. And this is why the art of memory and witness is so vitally important: it prevents de-historicizing. It stops it in its tracks. Together, they tell each of our truths as they are and were, not as we wish they might be. This is also why, during times of war, the first people to die are the artists and the truth-tellers.

In a short essay, Paramnesia 1996 at the end of her monograph Return: The Landscape of Memory, Sylvia de Swaan writes

Had I paid closer attention to my mother Etka’s stories while growing up, I might now be saved the trouble of excavating in the past like an archaeologist sifting through shards of broken pottery. Some things can never be put back together again. But back then I plugged my ears and averted my eyes. Me trying to become a regular American teenager, hard enough, without coming to school each morning with recycled nightmares in my head. I didn’t want to know about the old country with its dark and tangled history. I didn’t want to hear any more stories about pogroms and death camps. I didn’t want to be told about being hidden by a Polish woman in a sack of potatoes to save me from doom. I didn’t want her to look at me in that hopeless way and say mein armes kind (my poor child) …. Since 1990, I’ve made several trips through Eastern Europe to create present day connections with the regions related to my ancestry. I’ve strolled through towns whose names on the map once held epic connotations for me (“the war,” “the old country,” “the iron curtain”); inaccessible, exotic, and only faintly remembered from stories in my early childhood, filling me sometimes with wonder, terror, and longing…. (Paramesia 1996)

We have to pay attention to all of it. We have to bear witness to what we like and what we don’t, to what fits our narrative and what doesn’t, to the epic triumphs and stupendous failures of our species as though we actually recognize each other as fellow humans.

Without memory, the good and the bad, all is lost; we have no way to move forward.

Sylvia de Swaan 1941-December 7, 2023

Thank you for honoring my mother on a day where we all gathered to celebrate her life.

What a gift to share. First Simon sending you the box and then you sharing with us the stories of his mother. The patterns of the woven bag can be found in the story of your friendship. What a beautiful pattern you’ve woven together for us.