In 1998, in the early days of summer, I found myself paddling an old plastic kayak down the Santa Fe River in High Springs, Florida, a few miles northwest of Gainesville.

I was warned by my paddling companions to keep my hands in the boat and I took that to mean that despite the bucolic nature of the slow-moving river, shaded on both banks by hanging oaks, there were likely snappers and alligators lurking below its surface. It was a quiet paddle and easy for a new kayaker to get caught up in the fallen tree limbs that criss-crossed its narrower bends, and required laying flat against the stern like one would while playing limbo. I distinctly remember coming to the end of our trip, a few miles downriver from where we started, and seeing a family of baby turtles perched on a half-submerged log, lined up in size order, their heads to the sun, eyes closed, blissed out. I still wonder to this day how turtles would even know about size order. I’m convinced: we, in our arrogance, assume that we’re the only creatures on Earth with a sense of organization Everyone closes their eyes to the sun; everyone meditates in one way or another; everyone requires peace at some point. Everyone needs rest.

Kayakers are the Zen Buddhists of the water: they move more slowly and tend towards extrospection, and a close awareness and examination of the natural world that is both outside themselves and still very much interdependent.

Over the years since, I’ve done little paddling; there was the lake kayaking that Susan and I did on Coleman Pond, across the water from Alex Katz’s studio in Lincolnville, Maine, where we came upon a dead Loon floating on the surface. There was the short Penobscot Bay trip that we took from Camden to Curtis Island and back. And every time we’re up there — every September — we see groups of people, usually couples quite a bit older but a lot hardier than we, paddling along the shore in beautiful antique wooden kayaks that have been lovingly cared for over the years. Every September, I think to myself: I want to be those people, living close to the water, seeking out the edges of the coast, the places where shore and current meet, the places where the water is alive and moving and thinks to itself, as Brian Doyle wrote in Mink River, Rocks and pebbles and grains of stone and splinters of stone and huge stones and slabs and beaver and mink. Kayakers are the Zen Buddhists of the water: they move more slowly and tend towards extrospection, and a close awareness and examination of the natural world that is both outside themselves and still very much interdependent.

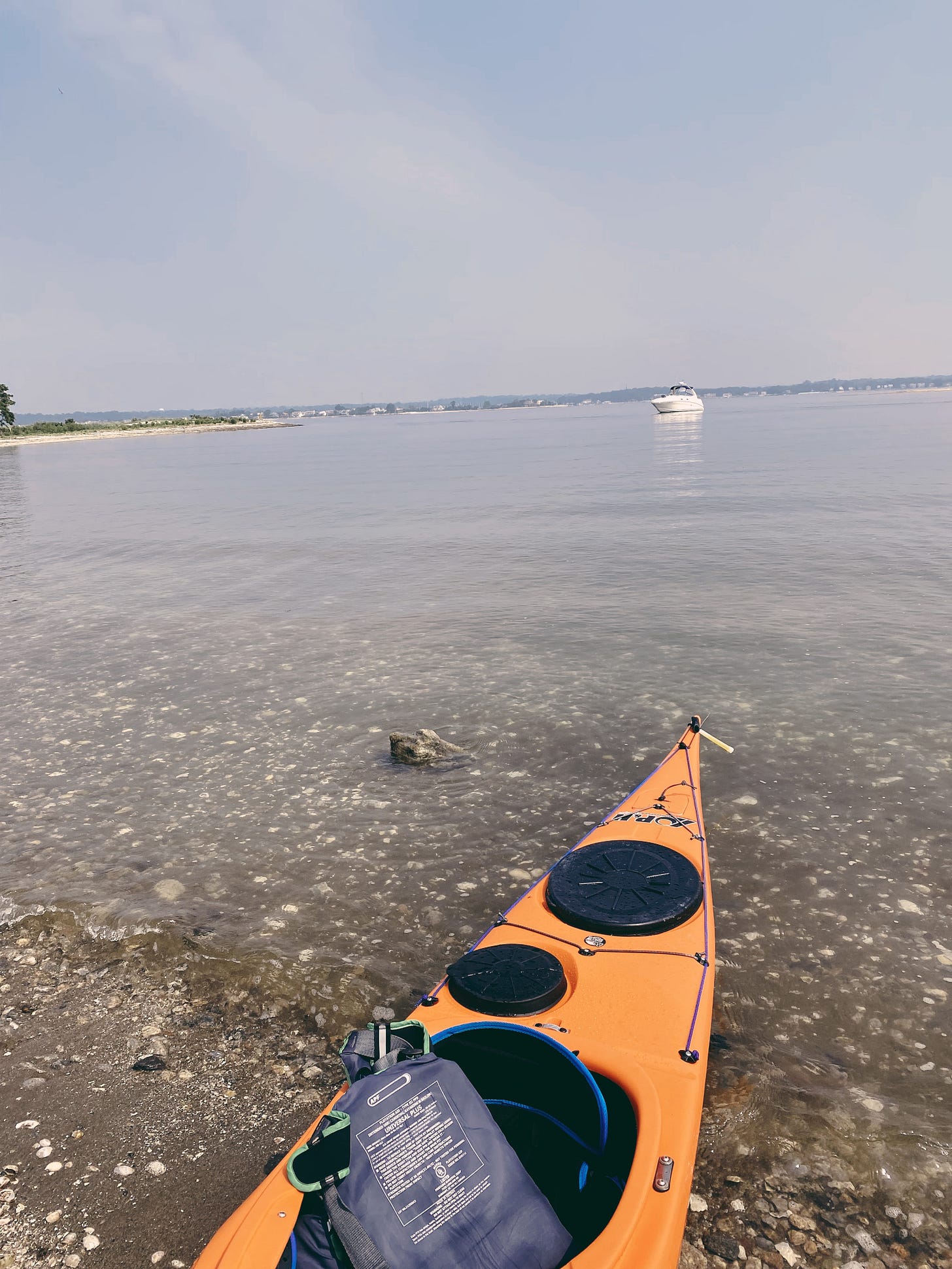

If anything, I’ve found that with the passage of time I am far less interested in speed and noise. I told Susan that this year, my birthday required two things: proximity to water, and a candle. My birthday fell on a Thursday; on Saturday, we arrived early at the sea kayak put-in on the Saugatuck River in Westport. She had signed us up for a sea kayak tour to Cockenoe (pronounced Ko-Kee-Nee) Island, a few miles offshore in the Long Island Sound. Another group of four joined us: mother, adult son and daughter, and father. There were two guides: one was the leader, and another, who pulled up the rear. The tour would take three hours in total including a stop on the island, where we would rest and stretch our legs before getting back into our kayaks and making the three mile return trip back to Westport. A little more than six miles, in total, according to my watch’s GPS.

I think to myself: I want to be those people, living close to the water, seeking out the edges of the coast, the places where shore and current meet.

Susan and I had done a truncated version of this paddle in 2018: we rented the kayaks, launched from the same spot, paddled out to where the river began to pour into the Sound, and came back. The river is lined on both sides with homes that are nothing less than extravagant: both old and new, wood and stone, they were beautiful but also a distraction, and it was hard to focus on the paddle, the water, the birdlife, the ebb and flow of the current. This time around, there was little to think about but the journey itself: it was the Saturday before July 4th and the water was crowded with yachts and powerboats, sailboats, skiffs, a brave middle-aged woman rowing a single scull. There were ship lanes to worry about, the heavy chop that sloshed brackish water into my cockpit (we had no skirts), foot pegs that kept slipping so I wound up using my arms rather than my torso to move my boat forward; there was the deceptively violent push/pull of the current against which I was paddling with every ounce of strength I had, to no avail.

It’s been a complicated birthday; I don’t love them — they make me feel very self-conscious, I miss my father, and yet I also want to mark them somehow: a typical Cancerian/Enneagram 2 (so I am told). My mother had been lovely on my birthday although we didn’t see her; the day would have devolved into her competing with us, and while I make no bones about the fact that not celebrating with her only child on their 60th birthday must have been difficult for her because she knew it was my choice, made for the sake of my own self-preservation. There have been financial issues connected to projects with slow payers. There have been health issues. There has been the recent breakup with wine as the result of the health issues. There is the unquestionable fact of age and the passage of time. I wanted peace.

The density of the Sound at high tide made it feel like I was paddling through pudding; I initially flew over the water like I was shot out of a cannon — hard and fast and leading the group, until my arms and back exploded in revolt. By the time we all made it out into open water, I realized that everyone else was far ahead of me — I was paddling for everything I was worth and literally going nowhere — and that it was just me and the second guide who was patiently floating along behind me. I did what I always do when I get self-conscious: I asked him if he liked to fish, and when he said he did, particularly for bluefish, I asked him if he liked to cook it and he said yes, but he couldn’t get it right, so I gave him my recipe. (Make a spicy garlic aioli, brush the fillets with the sauce, run it under the broiler for a few minutes until the top is golden and bubbling.)

When I finally made it to the island, everyone was already there, including Susan; it was embarrassing to be so exhausted that my arms were too weak to even pull myself out of the cockpit. We got back into our kayaks a few minutes later — they had all been waiting for me — and returned across the Sound, in the boating lanes and through a sailboat regatta, weaving around the yachts that didn’t see us, some piloted by inebriated celebrants. For the first time in years, I saw garbage floating in the water — not quite the Delaware in the Seventies, when it was dangerous to even be on that river — and it stopped my heart for a minute.

I paddled and paddled and hauled myself forward and groaned, and the harder I fought, the more slowly I moved. It brought tears of frustration to my eyes and I tried to not work too hard; I tried to move with the current and the chop, and to keep my eye on the dangers around me to whom I was invisible — the sailboats, the yachts, the fishing boats, the smoke in the air, the inebriated celebrants — knowing that this is life, isn’t it: you paddle and paddle and paddle and get nowhere until you stop fighting the current. I remembered back to the days when my strokes were powerful and my form good, and I wonder where they’ve gone. Time stutters and reverses and it is always yesterday and today. Maybe the greatest miracle is memory, wrote Brian Doyle, and I believe he was right, as I always do.

[RECIPE]

Simple Mussels

There was a time when Susan and I first got together more than twenty years ago, and made mussels for dinner a few nights a month. They’re fairly inexpensive, simple to prepare, and there might be nothing in the world like cooking them in a fireproof clay pot that might sit directly in the embers of a summer bonfire. You need nothing more than a loaf of good French bread to sop up the broth.

Serves 2-3 hungry people

1 tablespoon unsalted butter

1 large shallot, peeled and sliced

2 sprigs fresh tarragon, leaves chopped

small bunch parsley leaves, chopped

2 cups liquid of your choice (water, IPA, bottled clam juice, fish stock, dry white wine, white vermouth; use AF versions of the beer or wine, if desired)

3 lbs fresh mussels, rinsed and de-bearded if necessary

pinch salt (mussels can be salty, so be careful)

1/3 teaspoon freshly cracked black pepper

1 baguette for dipping

Optional: brown diced bacon or rounds of linguica in the butter and continue with the recipe

In a medium soup pot over medium low heat, melt the butter. When the foaming subsides, add the shallot and stir well, cooking until translucent. Add the tarragon and parsley, your preferred steaming liquid, the mussels, salt, and pepper. Raise the heat to a slow simmer, cover, and cook for two minutes, until all the mussels have opened. Discard the ones that haven’t.

Make it easy on yourself: bring the pot to the table and spoon the mussels into warmed shallow bowls, and pour the cooking liquid over them. Tear pieces of bread to dunk into the liquid.

You are very brave, Elissa, at this stage in life. This was a very interesting article.

I think you are quite brave, Elissa. You completed the kayak voyage, and it sounds exciting, and then, exhausting. As you reflected. Life is like that. Love knowing that your guide now has a fine recipe for their next freshly caught fish.