On this New Year’s Day, as the sun comes up and the world spins towards inexorable change, and our human stories get lost amidst the noise and yammer of politics and far too many screeching social media platforms, I say this:

It is not enough for a teacher of memoir to tell you that we are the art-making species; that it is our God-given right to create; that no child, having been given a pad and some crayons will ever say, to quote Elizabeth Gilbert, Nope, not feeling it today; that far more women than men withhold their storytelling until someone tells them it’s okay to do so (a broad generalization, but men usually just do it and apologize later); that you have every right to say whatever it is you need to say, damn the torpedoes. Some (not all) of these statements are accurate, and all require significant bravery. They all hold the potential for transcendence, and also danger. But not one of them unpacks the layers of what it is that makes us choose not to share our stories until the moment where we step through the scrim of worry/fear/concern/threat/self-loathing/panic that pushes us to the edge of the diving board, and off. Once we jump, we jump; there’s no turning back. Even if you tell your stories to your notebook and nowhere else — and sometimes this is appropriate because not everything is meant for publication — it can still be a terrifying prospect.

I came away with this understanding: that the act of writing one’s story is a spiritual exercise that all of us are called upon to do, whether we want to be published, or not.

In the writing sphere, we talk about it all the time: notebooks, process journals, residencies, the correct pen, the right desk facing the right way, the ritual of meditating or lighting a candle first or making a pot of tea. All lovely, and, for many of us, important and effective. But these foundational questions still exist as tripwires: who am I to tell my story? Is it mine to tell? Do I own it? What will happen if I write something when I’ve been warned not to? What happens if someone tells me that I’ve gotten the story all wrong?

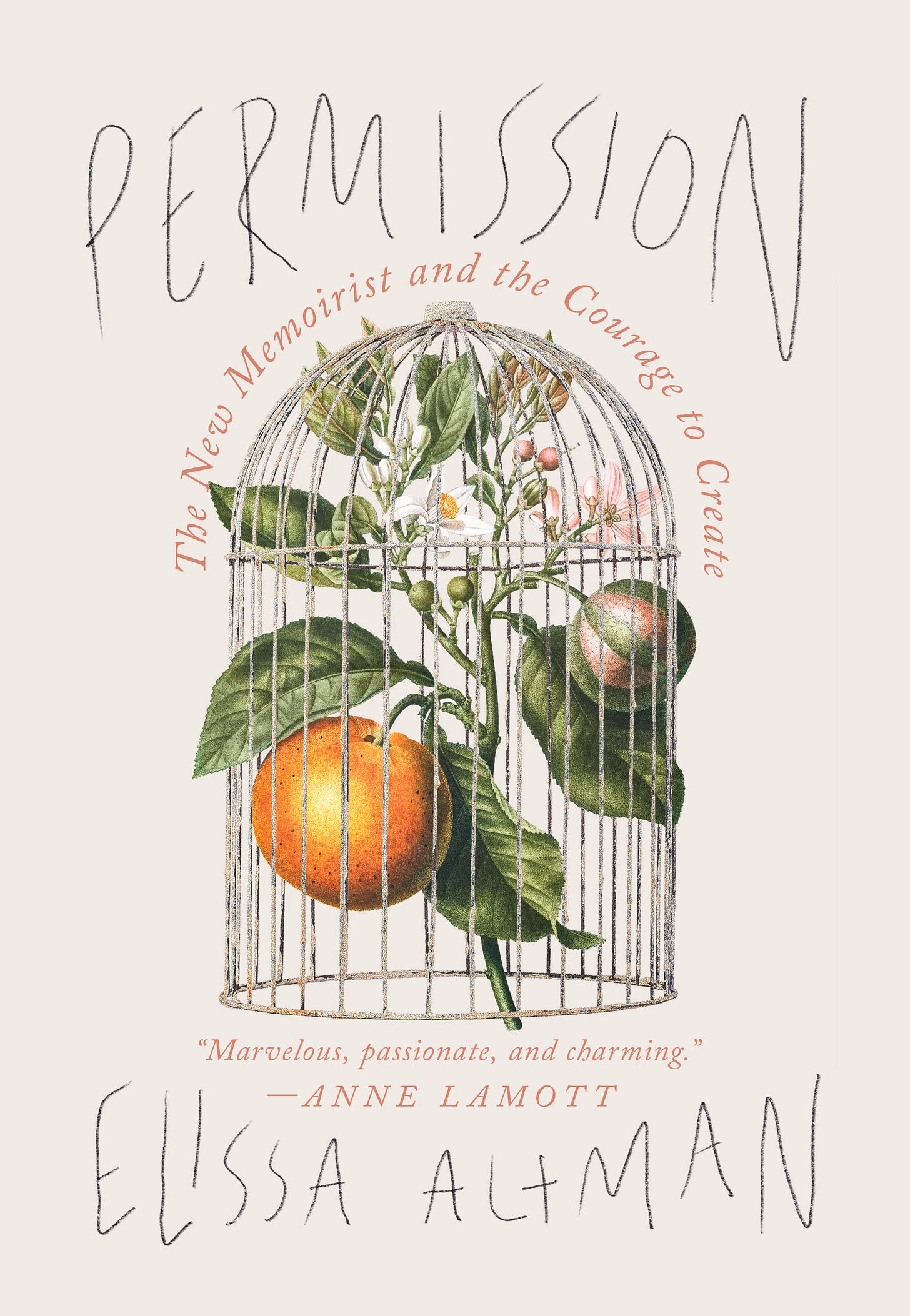

In March 2025, my fourth book, Permission: The New Memoirist and the Courage to Create will be published. It is vastly different from my first three books in that it is a hybrid memoir — one part craft, and one part personal context. I had written an entire draft before I realized that I couldn’t possibly create something that might help other writers and creatives without also explaining what compelled me to write it in the first place.

Permission came out of a decade of my own silence born of paralyzing creative trauma: I told no one about it — not my students, not my editors or publishers, not my teachers or my friends or my mentors — or what had happened to me during that decade. Permission had its deepest roots in the dangers of secret-keeping. It emerged from the muck and mess of intergenerational trauma, and the writing of a century-old story that, unbeknownst to me, was meant to be hidden. It is the story of what happened — emotionally, physically, spiritually, professionally — when a writer’s world imploded as the result of telling a simple but dangerous tale about one young woman’s heart-rending decision to leave her family, and the decision’s aftermath. Would it have been better not to tell the story I did? Maybe. But I could no sooner hide it than change the color of my eyes, because it touched every part of my life and still does.

Along the way, I peeled the onion: how do we tell difficult stories that belong to us but to which others claim ownership? How do we handle issues of revenge writing? How do we resolve the problem of making time and space for actually doing the work? How do we decide to take the risk and write about what has been hidden? How do we remain creatively generous? How do we write with humility and compassion about impossibly difficult issues (and people) that might be devastating?

I came away with this understanding: that the act of writing one’s story is a spiritual exercise that all of us are called upon to do, whether we want to be published, or not. Storytelling is an endeavor reflective of the human condition, and handled with care, it will move us to a place of compassion, humility, self-knowledge, and transcendence. As Robert Macfarlane writes in Underland, when the earliest cave dwellers took a mouthful of ochre dust and blew it at their hand held up to a cave wall, they were telling a story. They were saying Remember me; I was here.

The permission we give ourselves to tell our stories is how we get there; it is the key that turns the creative ignition, that cracks open the hard shell of our humanity. When you read something written by a person to whom you have no connection — no ethnic, religious, geographical, political, spiritual familiarity — that link, which might otherwise not exist, is what results from permission to write.

Storytelling is an endeavor reflective of the human condition, and handled with care, it will move us to a place of compassion, humility, self-knowledge, and transcendence.

At the beginning of this new year, I ask you to do this: amidst all the gadgets that will promise to accurately measure your blood oxygen level, or the diets that will render you svelt and metabolically younger, the promises to yourself to run a 5k this year or to stop drinking, remember to tell your story. Write it. Paint it. Scribble it on a cocktail napkin. Start there. Understand that some people will not be happy about whatever it is you do or say, some people won’t care, and others won’t notice. Predicting whose feathers will be ruffled by your storytelling is a moving target. But do know this: if it happened to you, if it — whatever it is — changed you or touched you in some way, it is your story.

Tomorrow, I will be sharing, for paid subscribers, an excerpt from Permission that I hope will nudge you to the edge of the diving board in 2025. Until then, I wish you the happiest and safest of new years, filled with good health and peace.

xElissa

I literally got chills when reading this passage:

<<It emerged from the muck and mess of intergenerational trauma, and the writing of a century-old story that, unbeknownst to me, was meant to be hidden. It is the story of what happened — emotionally, physically, spiritually, professionally — when a writer’s world imploded as the result of telling a simple but dangerous tale about one young woman’s heart-rending decision to leave her family, and the decision’s aftermath.<<

Thank you for writing this, Elissa. I can't wait for your book to come out.

I officially declared the first draft of my memoir done yesterday. My mother's response to the news was to tell me she was feeling "all kinds of feelings" about me finishing it, which is fair and also a not-so-subtle dig that she can't help, I think. Self-protection and excuses run in her veins, and I love her even so.

I'm looking forward to Permission. It will be good company in these next stages of the storytelling.