We were in Las Vegas in 1970; I was still a young child in single digits.

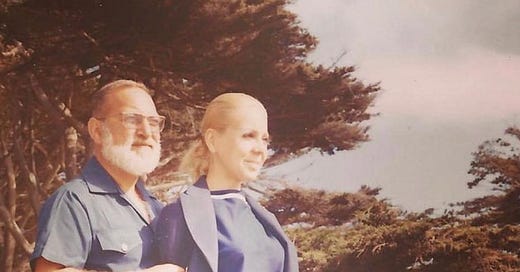

My father recently had a scary neck surgery, after which he was prohibited from shaving, and his beard came in chalk white, which made him look a lot like Ernest Hemingway. My parents had booked a room for three at Caesar’s Palace and after one day spent down at the pool where they were shooting a movie with Tony Franciosa — my mother hated pools but the fact of the movie and the handsome actor were enough to lure her outside for a few hours while I played in the water and my father documented everything with his Super 8 — my mother’s skin began to blister and bubble in a manner that terrified her. She demanded to be taken to a doctor, so the concierge helped my father find one who could see her that day. They left me with a hotel babysitter, and when they returned a few hours later, my mother’s legs were wrapped in damp gauze, which she was instructed to remove the next day.

He told me that I’m allergic to the sun. It makes perfect sense, she said.

What will you do? I asked.

Stay inside, she said.

Forever? I asked.

We’ll see, she said.

The actual diagnosis was Solar urticaria, which, in fact, is a rare allergy to the sun, causing angry hives.

Over the next three weeks — we were traveling out west from Las Vegas to California exactly a year to the day after the Tate-LaBianca murders — my mother refused to be outside unless she was fully covered up, for fear of a recurrence. But I was a child, and I wanted to be anywhere there was water and sun: a pool, the beach. Being very fair, I burned and tanned easily, and when my mother relented, she put me in a tee shirt with a picture of Flipper on the front, and told me I probably wouldn’t become allergic to the sun as long as I paddled around in something over my bathing suit.

My mother was not actually allergic to the sun; she’s fairer than I am, and she had gotten fried to a crisp while watching Tony Franciosa strut around the pool at Caesar’s Palace for hours. But my mother (still) believes that every affliction can be reduced to an allergy — cancer; influenza; my stepfather’s cerebral hemorrhage in 1997 — and her allergy to the sun, she felt, was proof positive that outdoor activities were too dangerous and anyone who was involved with them was risking, at the least, angry skin eruptions, and at most, death.

Of course, it was pure bosh, and her own athletic mother made sure that I was outside after school every day in good weather or bad. When it was sunny, I got sunburned — we all did — and slathered on aloe. (We never considered the fact that our ozone layer was being destroyed by millions of cans of AquaNet shellacking millions of up-dos in place from the early sixties straight through to the days of Farrah Fawcett and her flips.) But I never feared being outside until I got older, and saw how dangerous exposure to the elements could be.

The sun was just the least of it. There were undertows, riptides, Portuguese man-of-war like the one that nearly killed my paternal grandfather while he was swimming in the warm waters off Miami Beach; there was beach garbage like pop-tops and shards of glass and smoldering cigarettes (and in the eighties, syringes); there were shark, and sea urchins; there were stingrays, and lightning and hypothermia. In pools, there was too much or too little chlorine; people relieving themselves in the deep end to try and go unnoticed; getting kicked in the head by other swimmers in your lane; various horrific eye infections that spawned like bunnies.

You could be attacked by a bear or a mountain lion or, like Peggy Lipton in The Mod Squad, step on every rattlesnake from Bakersfield to Laurel Canyon.

Up on dry land, things weren’t much better. You could step on a yellowjacket nest while on a simple hike and go into shock; you could ski over the edge of a cliff if the run was too icy to make a good turn; you could climb a local mountain and get caught in a snow squall; someone could open their car door just as you ride by on your bike and send you flying headfirst into oncoming traffic; you could swamp your kayak running rapids, get knocked unconscious, and drown upside down when your skirt doesn’t release; you could get whacked by the boom on your sailboat when the wind suddenly changes and the temperature drops; you could meet predatory men while hiking the Pacific Coast Trail; you could get beaned by either your partner’s pickleball paddle, or the ball, or both, and lose an eye; you could be attacked by a bear or a mountain lion or, like Peggy Lipton in The Mod Squad, step on every rattlesnake from Bakersfield to Laurel Canyon.

Being outside is a very dicy prospect.

But so was growing up in New York in the 1970s, and I often forget this fact: that I barely survived riding the A train through Manhattan despite the presence of The Guardian Angels; that I barely survived the gun violence in my childhood community; that I barely survived using the third floor girl’s bathroom in my middle school; that I barely survived smoking a laced spliff alone in my divorced parents’ kitchen and thought it was a terrific idea to wash it down with a tumbler of tourist rum from Jamaica. Not that I had any addictive tendencies or anything.

I want to cold-water swim, but I also want to be wrapped in a large cashmere throw.

My answer to the terrors of growing up when and where I did was simple. My innate sense of self-preservation without which I would likely be long gone from this marble forced me into intense outdoor activity. In 1977, when I was fourteen, my father bought me a charter subscription to Outside Magazine. I became a one hundred lap-per-day swimmer. I learned how to downhill ski on icy eastern mountains. I was fearless, and only wanted to do one thing: move my body, absolutely all the time. After that first dopamine rush that comes with intense physical activity, I was hooked.

And then, in recent years, I became unhooked.

What happened? Is this inevitable? When did I become so fearful? Is this the first step on the road to frailty?

When did I become afraid of outside?

I want to cold-water swim, but I also want to be wrapped in a large cashmere throw. I want to learn to row on Megunticook — a massive, stunning lake near where I stay in midcoast Maine — but I also know that rowing a narrow little shell that is twelve inches wide is not for sissies or people with balance problems. I want to sail, but I get horribly seasick. I want to run a 5k, but I have bad knees and large breasts and a tiny fibrilliation issue. I want to walk England’s South West Coast Path, but I’m afraid I’ll slip over a cliff. I want to walk the Annapurna Circuit in Nepal, but I don’t want to pass out from hypoxia, or be kidnapped, assuming I survive the flight into Kathmandu.

(My friend Kathleen, who suffered from a brutal case of long covid in the early days before the vaccine, climbed Kathadin while recuperating; this is exactly the kind of thing she’d do. She also cold-plunged in Rockport Harbor in Maine on New Year’s Eve, but I digress.)

I do not believe that it is too late, and every day, I try to force myself to do something I would have done years ago, but not since I became unaccountably afraid: I tried surfing this last June, and I sucked at it. I may try it again. I step into the north Atlantic a little bit further every day I’m in Maine. If I have to buy a wetsuit, I intend to be a cold water swimmer, or at least a dunker. Yesterday afternoon, Susan and I spent two hours on a schooner in Penobscot Bay; we called the doctor, got the patches, and it was a gorgeous, life-giving few hours on the water.

Before we went to the wharf for our sail, I took Petey out to the beach for a walk, and met a woman about my age in a bright pink cycling jersey, a bright pink helmet, bright pink sunglasses, and bright pink panniers on the (not bright pink) gravel bike she wheeled over the rocks to get to the edge of the water. She introduced herself as Michele, and said she was cycling from ocean to ocean. She explained her route and told me that her husband had been with her for part of it, and was meeting up with her again in Bar Harbor, up in Acadia.

Ocean to ocean, she said.

I was astonished, and overwhelmed by her: her ebullience, her sheer delight at staying with hosts who share her love of biking, and helped her journey along with great places to stay, good food, and good conversation. I was amazed by her fearlessness.

I wanted to ask her so many questions: when did she start doing this kind of thing? Why? Was she ever afraid? How did she overcome it?

But she was on a schedule, and so was I. We shared our names, and I wished her the best of luck. I looked at her hands and legs, which were well-tanned from her ride, and I thought:

This person is not afraid of outside. This person is not allergic to the sun.

I took Petey home and Susan and I drove to the public wharf, climbed onto the schooner, and I felt the sun beat down on my face. Way out in the bay, we saw porpoises, a seal, an osprey.

I want to do it again tomorrow, and the day after, and the day after, for as long as I can; there is no time to waste.

I feel your joy! And it doesn't always have to be a big adventure to be thrilling. I've come to love the tiny microseasons of nature. There's something new waiting for us to savor every single day.❤️

Yes, there is no time to waste, and now I'll go watch TV.