Our work schedules change in the summer.

Susan works longer days and has alternating summer Fridays off, so the alarm clock rattles earlier than usual. The dog is still asleep, the cats are still asleep, I’m still asleep. A splash of pre-dawn light filters through the window over my dresser. For a long time, I just rolled over, but lately, I’m getting up with her. It’s not like me — I am not nor have I ever been a morning person and when my mother woke me for grade school, I would often fall asleep on my bathroom floor — and now, without alcohol in my life, I’m sleeping like a rock, which makes it even harder to get out of bed. Still, Susan’s alarm goes off at six thirty in the morning, and I hate six thirty in the morning; I’m trying to change that. But like wine with dinner, old habits.

Lately, though, I find myself looking forward to these early hours. Most days I lay in bed and read — actual books of the actual paper variety — until seven or so, and then I get up to feed the wild hordes and, if Susan is at her desk, walk Petey around the block. I make myself a cup of coffee and sometimes a hard-boiled egg, I check my email and try not to get sucked down the wormhole that is social media, and then I get down to work: I re-read the previous days writing and pray that it propels me forward which, if the stars are aligned, it sometimes does.

Stories suture up our parts against a primordial awareness that we are in pieces. They knit our bodies and our worlds into shapes we can use and that make sense to us, shapes that can break and be repaired in sufficiently predictable ways to allow us to live. - Emily Ogden

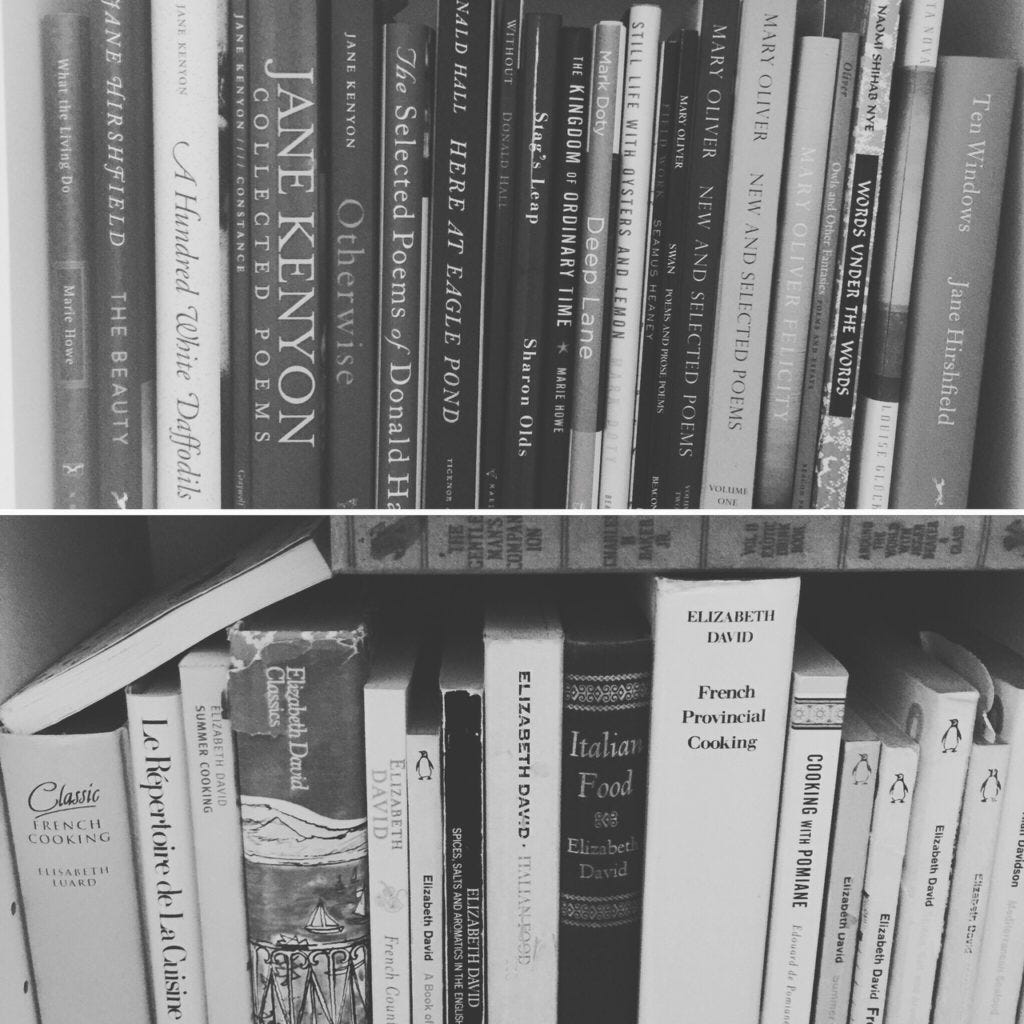

I’ve been reading a lot of poetry before I’m even upright, drawing from a stack next to my bed: Mary Oliver, Marie Howe, Hafiz, Jane Kenyon, Donald Hall, Jane Hirshfield., WS Merwin.

Where are you, Angel of Mercy?

Outside in the dusk, among the flowers?

Leaning against the window or the door?

Or waiting, half asleep, in the spare room?

I’m here said the Angel of mercy.

I’m everywhere – in the garden, in the house,

And everywhere else on earth – so much

Asking, so much to do. Hurry! I need you.

- Mary OliverAlways, there is Mark Doty, who many years ago showed me that the line between exquisite prose and poetry was gossamer. I picked up Heaven’s Coast after two of my best friends, a couple, died of AIDs within a year of each other in 1996, leaving everyone who knew them staring into an abyss, broken and wordless. I watched Peter and Tim — kind, brilliant men and practiced meditators who, every day at their country cottage rose before the sun to sip tea in their garden; get up early, Tim would implore — shrink and fade into vague glimmers of themselves, aging before my eyes as their lives became a litany of cocktails and T-cell counts and hospital visits. One by one, their friends began to die, their beautiful upstate New York weekend houses in bucolic places like Saugerties and Mount Tremper sloughing off cherished possessions like skin. Couches, dressers, dining room tables were passed around until there was nobody left to pass them to; estate sales and auctions turned up familiar place settings, and first edition leatherbounds that might have been read three years earlier in front of a fireside dinner party. I have pictures of Tim in my first Manhattan walkup apartment from the years before he and Peter got sick, ebullient and beaming over a blue and white Conran’s planter that I bought for his July birthday, which he used strictly to grow Genovese basil on his Chelsea windowsill. And I have his last Christmas gift to me: a small wall sculpture in the shape of an angel.

I clung to Heaven’s Coast like a blanket, and I let its words and its sorrow fill my ears and knit my heart back together. This is what good writing does; it’s a balm for grief. In Emily Ogden’s On Not Knowing, she writes Stories suture up our parts against a primordial awareness that we are in pieces. They knit our bodies and our worlds into shapes we can use and that make sense to us, shapes that can break and be repaired in sufficiently predictable ways to allow us to live.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poor Man's Feast to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.