the ancient childhoods of our youth

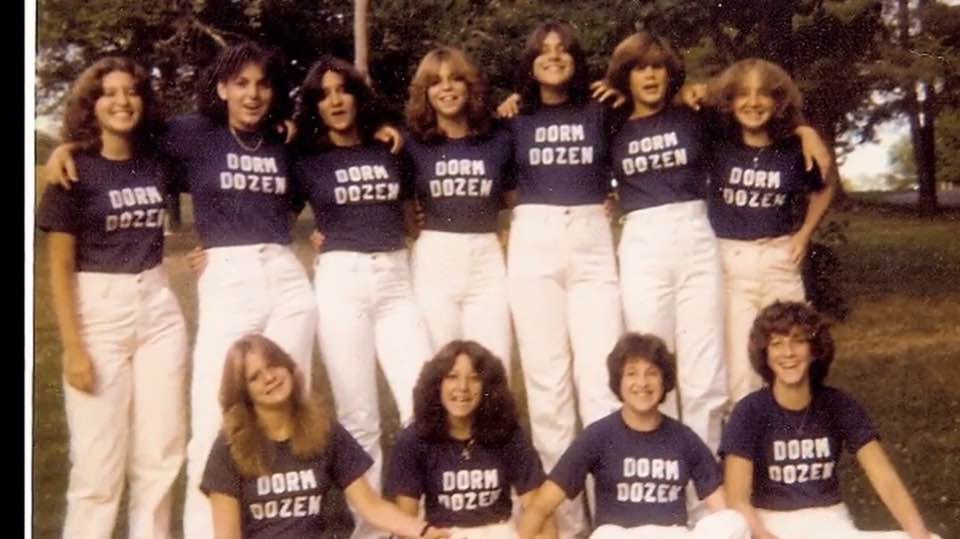

On My Return to Camp Towanda for Its 100th Anniversary and My 50th

Note: This piece was originally published in another form in 2007, when the alumni of Camp Towanda in Honesdale Pennsylvania lost a longtime camper, Bobby Hellman—the first of our generation to pass. It has been edited for dates.

Tomorrow, I will be driving back to camp on the occasion of its 100th anniversary in operation, and the 50th anniversary of my attendance in 1972. In the fifteen years since this piece’s publication, we have lost three more from our group—Lee Nordan, David Seitzman, and Alan Shmaruk.

This post is in their memory.

When I first went away to camp in 1972, my mother, in typically hysterical fashion, came down with a case of stress-related shingles.

A dyed-in-the-wool city girl, that's how my being at sleepaway camp affected her. At nine years old, and away from home for the first time in my life, I, on the other hand, spent the entire eight weeks sobbing (most audibly during meals, where I'd face the table of the camp doctor, Stan Foray, who bore an uncanny resemblance to my late father; Dr Foray responded to my pathetic weeping one rainy afternoon by furiously marching across the clattering dining room, lifting my chair off the ground -- with me on it -- and turning it towards the opposite corner).

But fifty years ago, when I wasn't homesick that first summer in camp, I was watching.

I was far less interested in my own giggling bunkmates, and instead watched the older kids and the counselors, the people who had made this wooded chunk of northeastern Pennsylvania their home for two months each summer, and whose lives, so far as I could tell, revolved around every July and August the way the earth revolves around the sun.

Some of the old-timers -- mostly teachers who had the summer off -- had been there since the camp's inception in 1923, a few years after the First World War ended, and less than two decades before the Second began. In the cavernous gymnasium, I watched the older Olympic plaques -- those hand-wrought, colorfully inscribed wooden paeans to the adolescent ferocity of what in many camps is called Color War (mythically re-named here during the 1940s, when many former campers and counselors found themselves in the service) -- and recognized a few of the 1930s-era campers' names: they were the grandparents of many of my counselors.

My camp was like Brigadoon; you got there, the past thickly enshrouded and informed the present and became indiscernible from it; you were safe no matter what your home life or your health was like, and while you were there, time stood still.

All those years ago (and unless I was on a playing field -- pabulum for a socially unpopular but extremely athletic child) I watched as the past and the present plaited together seamlessly, magically, and mysteriously; I watched, as the good ghosts of hundreds of ancient childhoods bore hushed witness to our young, privileged, rambunctious lives from the vantage point of cobwebbed rafters and dusty, torn bedsheet banners, of backstage social hall passageways scrawled with names long faded that can still conjure up, in the furthest reaches of this middle-aged camper's otherwise spotty memory, the way Olympics broke on a hot August night in 1972.

I often can't find my car keys or my reading glasses, and I sometimes forget when my estimated taxes are due; but I can close my eyes like Proust with a madeleine, and be in that spirit-laden social hall and tell you, exactly, how that night unfolded so very long ago, a year before the Vietnam War ended, when the world was just a little bit safer.

Sleepaway camp as a distinctly American construct doesn't always have this effect on people: some attend once or twice and never think about it again. Some, like my mother, never go at all. Some are dropped off by parents eager for eight weeks of blissful independence, while junior spends two months experiencing a series of firsts that grow more delicate, as weaving macramé belts gives way to a decided interest in the odd and interesting creatures living over on Girls' Camp. But for some reason -- and for most who attended -- my camp was like Brigadoon; you got there, the past thickly enshrouded and informed the present and became indiscernible from it; you were safe no matter what your home life or your health was like, and while you were there, time virtually stood still, the way it did for Bobby Hellman.

I never knew Bobby personally but I close my eyes and the years compress and I can see him vividly; several years older than I, Bobby's significant special needs rendered him older looking far earlier than they should have, for anyone. In a camp where athletic prowess was supremely prized and rewarded, and exigent social cliques were sometimes the norm rather than the exception (at least on Girls' Camp; maybe boys are different), Bobby's illness precluded much involvement in either. For him, it didn't seem to matter, although it certainly must have: while young people can indeed be cruel to each other, entirely unforgiving, and lacking in compassion, we at camp gave Bobby a very wide berth. Perhaps we were afraid; maybe, as children, we just didn't know what to say. So we said nothing; we just watched.

So vibrantly clear are my memories of my past at camp that some of my friends have actually worried about my connection to the present. But as a writer, I can get away with it. Mostly.

But Bobby watched back, a quiet, deeply devoted, furtive chronicler of the eight weeks each year that, despite their trials and inherent difficulties, also clearly offered him a peaceful respite from the many challenges that he had been faced with as such a young man, and that he dealt with bravely, humbly, and without complaint. One of his campmates, now in his fifties sixties, told me that Bobby could remember more about the former's life at camp than he himself could. As a watcher, I'm not surprised. That's what watchers do.

Over the years, since being back in touch with a few of my former counselors -- now very dear friends, and all far closer to me in age than I ever could have fathomed so long ago -- I've been gently accused of living in the past: detailed, minutiae-packed stories of camp are never far from my lips, and I often find myself humming camp songs while I'm cooking, or walking the dog, or driving, much to the head-shaking bemusement of my wife.

In my mid-forties late fifties, I can't let go, no matter what I do.

So vibrantly clear are my memories of my past at camp that some of my friends have actually worried about my connection to the present. But as a writer, I can get away with it. Mostly.

Sometimes, I'll find myself on my camp's alumni website, as I did recently. A January 2007 entry on the message board was from Bobby Hellman:

If any one from Towanda has any old olympic booklets with just the covers, judges, generals and camper captains plus group splits. please let me know. maybe we could work something out. please contact me. thanks.

Group splits?

Deep in the throes of middle age, camp clearly remained, for Bobby, his safety net, his peaceful place, where time stood still. And so when he died in 2007 at 49, emails flew, phonecalls were made, and people who didn't actually know him, but who remembered him clearly, and who haven't spoken to each other in three decades, reached out across the stiff constraints of time, distance, and circumstance, to suddenly talk about this man for whom camp unmistakably was -- and remained -- life. If he -- and we -- had only known.

"Maybe it's just that we're getting older," one of my friends said, at the fact that Bobby, unbeknownst to him, had, in the saddest of ways, brought us back together. And indeed, she's right: we are all getting older —- some of my camp friends are now young grandparents —- and moving into the next phase of our lives. Bring people of a certain age together, and surely, the conversation will turn to aging parents and children going off to college; to hot flashes and AARP offers clogging up the mailbox in the most annoying of ways; to the people we used to know, and who are suddenly gone.

Where our camp is concerned, though, bring us together and it's 1972 again; this is just our collective past plaiting seamlessly, magically, with our present, like Brigadoon. And Bobby, from the knotty walls of his beloved gymnasium, the scrawled-upon backstage passage in the social hall, and the hand-painted Olympic plaques dusty with the good ghosts of our ancient childhoods, will always be watching.

In memory of Lee Nordan, David Seitzman, and Alan Shmaruk.

It doesn’t matter if I’ve read this once or one hundred times, I cry with an intimate knowledge of these times in your life - and mine

I love this peek into your youth. Reading (rather devouring!) Motherland again last winter left me hungry for more, more, more.