a plate falls, a glass breaks, and suddenly, your grandmother is gone again.

Questions on Love, Memory, and the Corruption of Time

This morning, while going through my mother’s monthly bills, I made the discovery that she spent $400 on makeup over the last two weeks.

(I instantly shut down her emergencies-only credit card and called her store of choice to put them on high alert; they were incredibly helpful.) Apart from the fact that she is pretty much housebound these days (except to visit me, which requires two of us to get her in and out of the car and up the two steps into our house, or to go to a medical appointment) and receiving Medicaid, there are not a lot of reasons why my mother, who is eighty-nine, would need to spend $400 on makeup, which is an easy number to hit if you’re buying the high-end stuff from, say, Saks, or Bloomingdales, or Harvey Nichols.

My mother and I have been black belt emotional cage fighters since I learned to say No at age eleven, but I’ve lately been trying to pick my battles with her for the sake of my own health and sanity. I don’t want her last months/however-long to be filled with enmity and want, and I also just don’t have the energy anymore either (and if I did, it should go to my wife and my marriage and my health, and not some ancient thicket of psychic brambles straight out of a Grimm’s fairy tale).

Four-hundred bucks = a lot of makeup. I’m not going to quibble about her buying the odd $30 lipstick, although it admittedly rankles me because we support her and have been doing so for ages, and as a writer and designer, this is not ever easy for us. I sometimes wonder: if we’d had children and had to support those children as one does, how would she have responded? If she was having a bad day, would she have lashed out because: less for her? How would it manifest? Would it show up in subversive ways, always planned ten steps ahead of me?

I say this not to raise eyebrows or to garner pity, and if anyone says Oh but she’s been so good to you, I’ll delete it instantly because it is very, very complicated. We’ve had good moments over the course of my lifetime — they come in spurts — but mostly not: a lot of unpleasantness that, once absorbed by me, I managed to metabolize into humor. She never expected to have a baby, and was pregnant with me for six months before it even occurred to her that that’s why she couldn’t get her rings off or why her period had stopped. What we have had is this crazy whirlpool of codependent michigas that has defined us and who we are together and separately since the very beginning, like Debbie and Carrie: I left for sleepaway camp in 1972, and she instantly came down with anxiety-related shingles. (Postcards from a 9-year-old homesick Elissa read I AM HAVING FUN HOW ARE THE SHINGELS WHAT ARE THE SHINGELS.) She was apoplectic over some ridiculous infraction when I was a freshman in college four hours away, and on a Saturday night, she called every room on my (enormous) dormitory floor, somehow figuring out that each room was one phone number up from the neighboring one, looking for me so that she could give me hell. I used to wonder if I’d been imagining this all along because time has a habit of skewing accuracy, so I recently asked my college best friend, now a grandmother, if she remembered it, and she said Oh yeah…I remember that night. When she said that, it was like having a bucket of C-PTSD slop flung at me: yes, here is the shit that you went through. Don’t forget that you went through it and that you survived it. But make no mistake: it was real.

Must we carry someone else’s troubles and traumas through our own lives, where they further embed themselves in our DNA, until we work really hard — therapy for some; ayahuasca for others — to free ourselves of them?

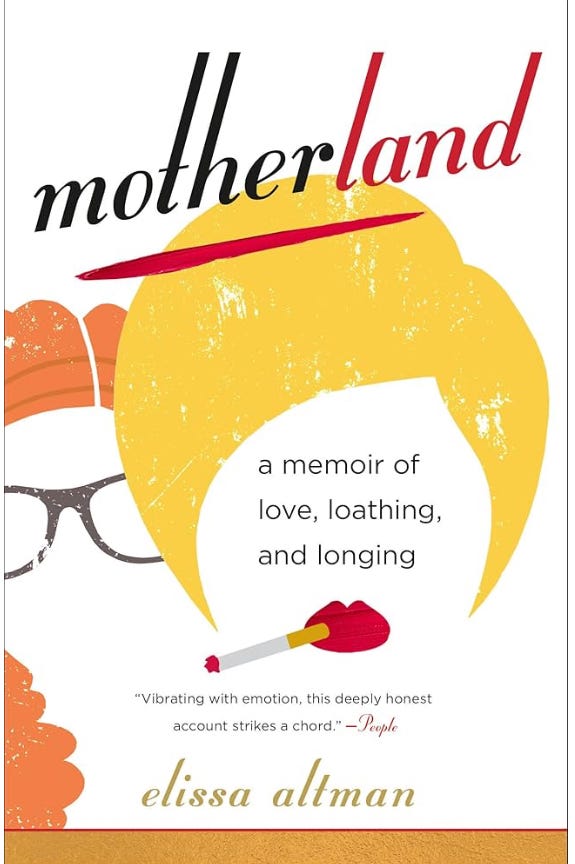

Although I wrote a book about us in 2019, there’s a lot that I don’t remember clearly anymore, because my brain is running interference for my heart. The body is funny that way: various bits and pieces will step in if they think one’s grief is too great, or one’s trauma too complex, and they’ll shut down the works until a later date, when it proverbially bites you in the ass. Which is why, I suspect, I’ve been able to get through the last few months relatively intact: I can actually feel my body slip into neutral gear, like water that is 93.5 and incapable of being felt by human skin. If I am going to manage my mother’s affairs for the duration, it seems that I can only do it if I go into emotional lockdown, devoid of rage and resentment, of anticipatory grief and the tentacles of our enmeshed history. Apart from the last two weeks, when I’d spent 90 hours dealing with the horror show that is New York’s managed Medicaid system and ended up exhausted and face down in my keyboard, sobbing, there’s been nothing. Just: nothing.

How are you, my neighbor asks when I’m out for a walk with Fergus. Fine. I say. Come for a barbecue. Tra-la.

Just: nothing. Like after I had the Covid stroke in 2020 and discovered that any spiritual connection I once had was suddenly gone. It was not like I was in spiritual crisis because I didn’t believe in anything anymore; it was just gone, as though I were staring into a black hole. (I have since learned that this is actually a neurological thing.)

You’re such a good daughter, my mother’s physician’s PA said to me when I brought my mother in for an appointment last week so that they could see for themselves her current condition, and they were horrified.

Naw—I said, rolling my eyes. I have to do this. I have to make sure she’s alright.

And I do. I feel morally obligated in the way that you are morally obligated to grab a two-year-old as they run into oncoming traffic. Also, I know her stories, and her stories are my stories because they’ve defined so much of our life together. We’re like the human version of the intersection on a Venn Diagram. There was the time she was singing on the Galen Drake Show and a chimp stuck his hand down the front of her dress on live television and the right-wing sponsors thought she planned it (still stupid after all these years) and threatened to pull their support — I heard this tale constantly, first as a child, and then as an adult. There was the time she went to The Concord Hotel with a girlfriend in 1960 before she met my father, and took up with Dick Shawn for the weekend. There was the afternoon when, she tells me, she was making out (her words) with Bernie Wayne in his Brill Building office when Paul Vance burst through the doors and sang them a (cringey) song he’d just written for Bryan Hyland: Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini. There are the plates that had been given to my grandmother as a wedding present in 1933, and the one that my mother dropped when I was home from college on a visit, and how she felt like my grandmother died all over again when it shattered into pieces at her feet. Object-as-memory.

I don’t have much of her left, my mother said, cleaning up the shards from the kitchen floor. These were her favorites.

If I am going to manage my mother’s affairs for the duration, I can only do it if I go into emotional lockdown, devoid of rage and resentment, of anticipatory grief and the tentacles of our history.

A corruption of time: it circles backwards and forwards and overlaps. When her stories are no longer being told, where will her history go? Will it vaporize? We, in flesh and blood, are made up of our stories — we are the storytelling species — so when we lose their source, is it up to us who are left behind to continue telling them? Does another person’s past become our present?

Must we carry someone else’s troubles and traumas through our own lives so that they further embed themselves in our DNA, until we work really hard — therapy for some; ayahuasca for others — to free ourselves of them? Can we ever get rid of them? Is there guilt or shame involved in even wanting to get rid of them? Or should we just carry them into our own futures with some degree of grace until they shrink in size, like an object in a rear-view mirror that slowly disappears with distance? (These are all rhetorical, but important to think about.)

I am a memoirist and a teacher of memoir; that is my work. I make my living by combing through the tangles of memory the way I once combed through the knots in a little girl’s long hair back when I was a camp counselor. We write, to quote Dani Shapiro quoting Jayne Anne Phillips, to keep sorrow from being meaningless. Memory inhabits and informs me; it enables me to make sense of what has been a complicated and sometimes fraught life that, according to at least one shrink, I had no business surviving. But I did, and so I wonder — as I think about my mother in her last days with her stories and her $400 makeup orders and the men and Zippy the Chimp sticking his hand down her dress while wearing a blue snowsuit on live Eisenhower-era television — is this where grace comes in? Is grace the thing that happens when we pick up the shards? Grace as undefinable, curious, infuriating, instructive, destructive, transcendent, heartbreaking, heart-saving?

Maybe. All I do know for sure is this: Claudia Rankine was right when she said You can’t put the past behind you. It’s buried in you; it’s turned your flesh into its own cupboard.

Upcoming events:

8/7/25 - East End Books, Provincetown: reading, q&a, signing

9/16/25 - Zibby’s Bookshop, Santa Monica: in conversation with Annabeth Gish, q&a, signing

9/18/25 - Book Passage, Corte Madera: reading, q&a, signing

Workshops:

8/4-8/8/2025 - Castle Hill/Truro Center for the Arts: Permission to Write the Story You Must Tell (WAITLIST available)

Spring 2026: Kripalu: Permission: The New Memoirist and the Courage to Create - stay tuned for final dates and sign-up

It's puzzling why we feel indebted to family, even when we don't like them. My 27 year old and I discussed this topic just last week. He, is an only child and felt he would not take care of a family member who was not kind or helpful. He's a very clear boundary on this subject and is a logical thinker (physics major). I have two siblings 5 and 9 years older and I told him that I would help them unconditionally. That's what family does if you were raised to believe you should. I was. My brother was always just one step ahead of living on the street. I was sure I would have to care for him in his old age, it worried me plenty when I was young. I never had a large income and lived in an 800 sq. ft house. How would it even work? In the end he passed away early and now I could only wish I had him to burden me. It helps that he was such a kind smart, person but clearly with some mental illness. My sister and I have a strenuous relationship. I will help her too if she needs it but being so different I would not support her with the same joy. We all have so much to sort out. Stay afloat and stay well. All the best!

So much to identify with here - I must get a copy of Permission.