Take my hand quick and tell me,

What have you in your heart.

-A.E. Housman, A Shropshire Lad (XXXII)When I first began this newsletter a few years ago, I was committed to writing about sustenance in all its forms.

My background is in food — I was a food writer for many years, won a James Beard Award in 2012 for narrative work, briefly attended cooking school in the late 1980s, and worked in the book department at the (tiny, narrow) original Dean & Deluca down in Soho, where my regular clients ran the gamut from Jean Michel Basquiat and Eric Fischl to Isabella Rossellini, Joel Grey, and Edna Lewis. After being offered a job as sous chef at a long-defunct Chelsea restaurant called Eze — one of the few at that time that was chef-owned by a woman — and learning what my hours would be, I searched my heart for why, exactly, I wanted to be in this business. I was a good cook, but completely disinterested in gastro-pyrotechnics. I truly loved culinary anthropology — why, for example, is Toulousian cassoulet different from Castelnaudrian, and how much of an impact did the ancient dish, cholent, have on them, or they on it and, eventually, pre-colonial baked beans. I loved knowing how to make a ballotine, and I could probably still do it if I needed to. And I loved knowing why Bandols are so high in alcohol, and when to match a Piemontese red with fish. But, and this is key, I’d rather make a tarragon-stuffed roast chicken on a Saturday night and eat it with my fingers in front of the fireplace, sitting next to my wife with the dog at our feet. This is not in any way romantic or cliché. It is an understanding of what sustenance is (at least to me), what it means, why it is a fundamental part of the human condition, and why we especially need it now.

When you remove the element of human reason from the equation, you also remove any possibility of truth and empathy. You return to the existence of a flat earth and flat heads, of bleeding with leeches and witch trials.

I remember hearing my father tell a story of driving home one night from work. It was 1989, and he was living in easternmost Brooklyn and working two hours away on Long Island, which required a very long and sometimes dangerous commute-by-car on the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. He was sixty-six, having had two quadruple bypasses and two abdominal surgeries to repair a massive hole in his small intestine; at nineteen, he had been a night fighter pilot in World War 2; as a three-year-old, he had been abandoned for a few years by his mother; he had been engaged five times to women his family wouldn’t approve of; he married a bombshell who had been on television and their marriage collapsed sixteen years later in a conflagration of cruelty and infidelity; he was, for twenty-one years, creative director at a famous Manhattan advertising agency; a decade later, he experienced personal bankruptcy after which my mother left him; he lived with clinical depression; against all odds, he found the love of his life when he was fifty-nine. She happened to be a trauma therapist.

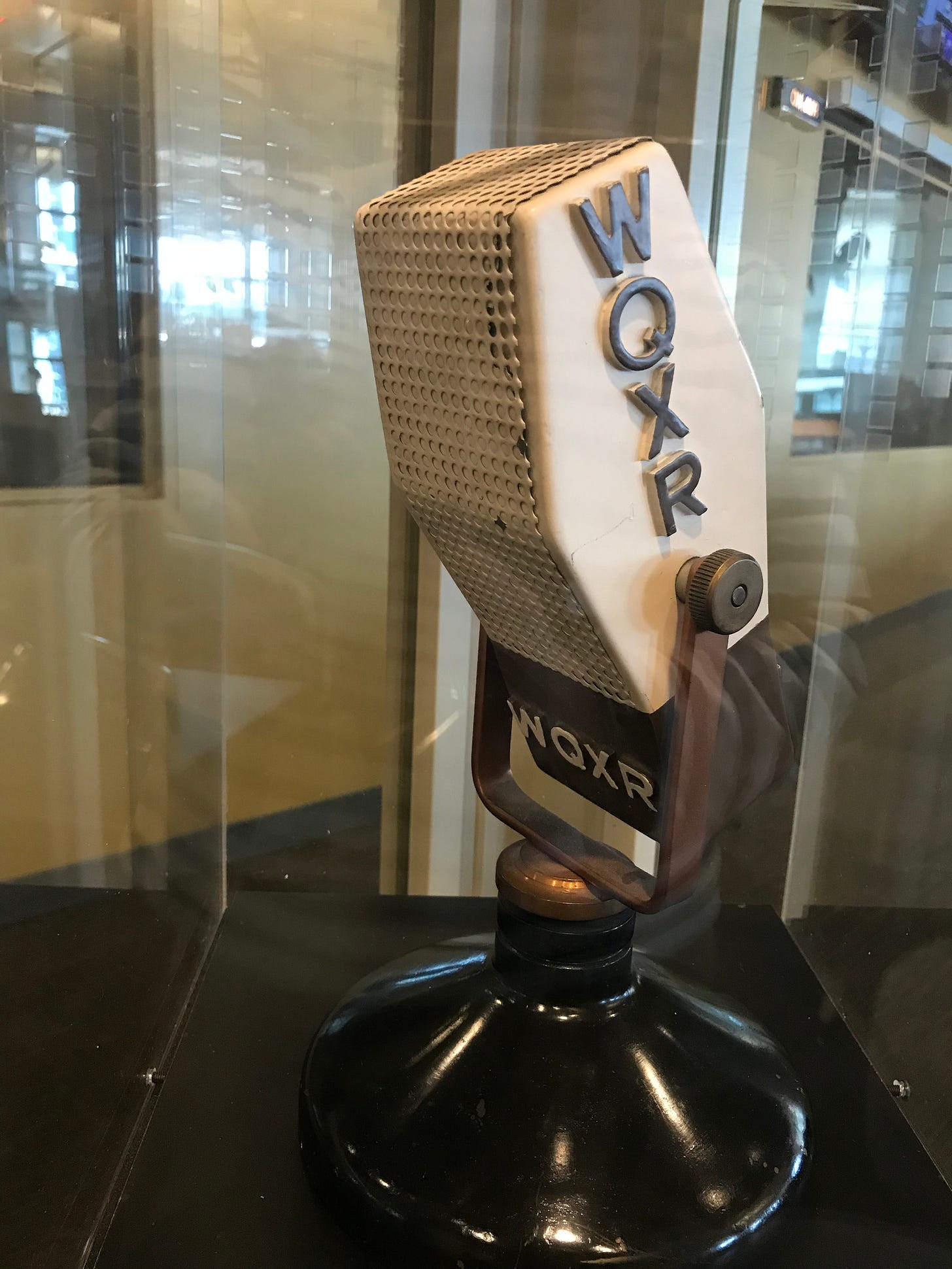

On that night, though, driving home from work in the rain, this big, broad, complicated life receding in his rearview mirror, my father pulled over onto the shoulder, applied the parking brake, and tuned in WQXR. He listened to Vladimir Horowitz play Chopin’s Etude in C-sharp minor; Horowitz had died a day earlier. My father told me this: he rested his head on the steering wheel of his Toyota to listen. He was constitutionally and viscerally exhausted, and he wept like a baby for everything that had once ever been, everything that he had lived through and seen, and the thousand big and little ways his heart had broken over the years and the thousand ways in which it had been knitted back together with the music of a stranger who, born in 1903 in Kyiv, Ukraine, provided the sustenance my father needed to put one foot in front of the other, and keep moving forward. Left foot; right foot, as my friend Anne says.

You end up with creatures, just creatures, who harm for sport, and who think — because it sometimes makes them laugh — that it’s just fine. And that it’s entertainment.

So when I think of sustenance, I think of good roast chickens in front of a fireplace. But I also think of the music that heals our quivering hearts in an ineffably personal manner. I think of the walks to the sea that my friends take in the frigid dead of an English winter; I think of the scores who saved the animals during the California wildfires. I think of Ukrainian soldier, Taras Stolyar, in uniform, playing his bandura with Sting singing Shape of My Heart.

This is sustenance. This is what it is, and this is what it does: it sustains us like air and water so that we can schlep ourselves forward through life, facing every manner of hell and tragedy while maintaining our humanity and knowing, at the most unthinkable moments, that there is beauty and grace to be found. And I say without a shred of hyperbole or drama: those two things — beauty and grace — are life.

Sustenance feeds us, body and soul, at moments of profound, systemic, national grief the likes of which many of us are experiencing for the first time in our lives.

I have been reading, everywhere, short little snippets about self-care during the times we are in. I’ve written here about how our one mistake in trying to unravel what is happening in front of our eyes is believing, somehow, that those at the controls can be reasoned with, and that one can appeal to their sense of human decency. But this is not the case, and this is where it all goes off the rails. It is very hard to fathom this because when you remove the element of human reason from the equation, you also remove any possibility of truth and empathy. You return to the existence of a flat earth and flat heads, of bleeding with leeches and witch trials. You remove those things that separate us from the rest of the animal kingdom, like opposable thumbs, and big, advanced, evolving brains that can somehow marry science and faith in the same whisper. You end up with creatures, just creatures, who harm for sport, and who think — because it sometimes makes them laugh — that it’s just fine. And that it’s entertainment.

I am trying, right now, to delineate between self-care and sustenance. I desperately (for example) need a pedicure; everything from my ankles down looks like I’ve been marching through the trenches, and, like my dad, all of my stress and anxiety goes as a rule straight to my feet. I need a massage because I’m spending too much time sitting at the computer every day, my neck seems to have disappeared, and my head appears to now be directly attached to my shoulders, like Ed Sullivan. A few months ago, in response to my level of stress, my hair started to fall out in clumps again, the way it did when I was twenty-two and living with my mother, who was abusive every hour of every day I was living under her roof; I need regular acupuncture to help restore blood flow and reduce my anxiety level. I need to wake up earlier every morning and take the dog-walking job off Susan’s hands, but my body is asking for rest so I’m trying to give it what it needs while also trying to be a decent spouse. The problem is: Susan’s body is likely asking for the same thing.

These things, I think, fall into the category of self-care, but they are different from sustenance, which feeds us, body and soul, at moments of profound, systemic, national grief the likes of which many of us are experiencing for the first time in our lives. Some of us are so young that we never heard The Stories, nor do we know the dangers. I have a dear friend who survived the Guatemalan Civil War, and who has devoted her life to feeding people, to her family, and to her profound Catholic faith; this is her sustenance. I have a neighbor whose mother was chased on foot by the Nazis for four years, and who, visiting Connecticut, panicked whenever there was a thunderstorm; she lived into her nineties and devoted her life to the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren I’m certain she thought she’d never live to see, and to standing in her Bronx kitchen and making kreplach as fast as her family could eat them; this was her sustenance. My mother-in-law, the tenth child of a subsistence farmer, lived with paralyzing agoraphobia; her sustenance was standing in her garden nine months out of a New England year, with her hands in the soil. I had a father who lived with a debilitating fear of abandonment and clinical depression; he devoted his life to storytelling, reading, his family, and Vladimir Horowitz playing Chopin; that was his sustenance.

Sustenenance comes in all forms and shapes, and there are people out there who write about it far better than I do; there is Maira Kalman and the honey cake in times of utter doom that she often speaks of. There is Anne Lamott and her gifts of grace — the women at her church who helped raise her little boy when she had absolutely nothing. As I tell my writing students: begin with the mundane. Honey cake and church ladies and Vladimir Horowitz are nothing to roll one’s eyes over. They are where sustenance lives.

So you might ask yourself, whether you are in the States and are at risk of losing the social security that you have paid into your entire life along with the roof over your head (like my mother, and my wife, and ultimately, me) or the Medicaid that, if you are below a very low income threshold, pays for the personal medical aides who get you from your bed to the bathroom (like my mother), or in Maine, where your state’s lifeblood will be snatched out of your coffers because your governor had the guts to say No, You don’t get to do this to my people, or in England, where a short 1700 mile trip east will take you straight to Kyiv: how will you sustain yourself. How will you feed your heart.

Because: you have to feed your heart

This writing, your personhood and gift are sustenance. I mean it. I was pulled through an emotional knothole today, and I just settled on the couch to read this and I wept at its truth and beauty. Which I’ve been needing to do for weeks. Thank you for feeding my heart today. I really didn't have it in me to even shop for it.

As several have said, thank YOU for offering sustenance. I cried while listening to the Ukranian soldier and Sting making music and reading your words. I'm with you in the pleasures of what we jokingly call around here "fingering a chicken" together - I'd choose that any day over fancy food. Thank you for uplifting the essential soul need for sustenance and for tuning to what that is for each of us. I'm listening now to that last Sting song you posted and tears are brimming as I type, while a pot of clam chowder (with all the butter, bacon, and cream, fortunately or unfortunately) is simmering on the stove. I'm reminded of Mark Nepo's iconic line, "I am sad and everything is beautiful." That feels like the most honest ground we can stand on these days. Thank you for your sustenance. It matters.