My maternal grandfather was a taciturn man, and such a dead ringer for James Joyce in his later years that people used to stop him on the streets of Williamsburg Brooklyn and ask for his autograph.

He was not a man naturally prone to joy: he didn’t know his father well, had a brother with mental illness that made him a danger to his family and community, married a woman who was a lesbian, had a longtime romantic entanglement with the Mother Superior of a local parish that he supported financially until the day he died, kept a flock of homing pigeons on his roof, and suffered from body-quaking Parkinson’s — the family illness — much of the last days of his life. He died when I was very young but I remember him distinctly and specifically for his kindness to me; he came home from Brooklyn to Queens only on Friday nights and I waited for him with my mother and grandmother in a little park across the street from our apartment, and not far from our subway stop. And before he had to go back to Brooklyn on Saturday to reopen the furniture store he owned on Grand Street, I would make him laugh — head-tossing-howling-until-tears-rolled-down-his-face laughing— by singing this drinking song for him, the first song I ever learned, taught to me by my former Naval aviator father:

Drunk last night, drunk the night before; I’m gonna get drunk tonight like I never got drunk before, cause when I’m drunk I’m as happy as can be, cause I am a member of the Souse Family ….

Nothing, my father would tell me years later, made your Grandpa Phil laugh harder than hearing you sing The Souse Family.

I was three years old.

Right around the same time, I discovered — I don’t know how this happened, or when, or why — that I liked the taste of beer. It wasn’t the end result that I wanted; it was the fact that I just didn’t like sweet-tasting juices, or milk, or water: I liked (and still like) the flavor of bitter, which is probably odd for a young child. And when my parents and I were driving home to Queens from New Jersey one Sunday afternoon, I apparently kvetched and screamed and cried from the backseat of my father’s Barracuda until he stopped, bought a six pack of Schlitz, popped one for me, I drank maybe three gulps of it, and he threw the rest of it away at the Vince Lombardi Rest Stop. I have the vaguest memory of him carrying me into our apartment building, thrown over his shoulder like a sack of potatoes. When I told a therapist this story a few years ago, she said So that was your first blackout, and I said Oh for God’s sake no it wasn’t, and I still believe I was right. Because we were Jews, and we were taught that Jews don’t drink.

There’s a long time in me between knowing and telling, wrote Grace Paley.

But when I sang the song for my grandfather, it elicited a response that delighted me: I had the power to make my grandfather laugh. This man — he had had a very hard life and still managed to devote it to keeping his family safe, and to philanthropy (during the war, he paid for the parochial school education of two young Italian boys who had been orphaned by the war and brought to the United States by the St. Vincent Society, to which the aforementioned Mother Superior was connected) — never laughed, but he enjoyed hearing his only grandchild sing a completely ridiculous Navy drinking song, and it gave him joy. And somewhere in the core of my being, a tiny nugget of truth started to beat on its own like a heart: having inherited my father’s sense of humor — he was a truly hilarious man who also lived with clinical depression, as do I; humor and sorrow share the same DNA — I discovered the fact that alcohol, in any permutation be it actual or in the lines of a drinking song, made me funny, and my funny had the power to make other people laugh.

My father taught this old Navy drinking song far and wide: a few years ago, having found a friend of my stepmother’s who I hadn’t seen in more than two decades, she told me that one of her last memories of my dad before his accident was teaching her two year old daughter how to sing The Souse Family. She — the woman who told me this — is a therapist, as was my stepmother, and still, it was funny, mostly because it’s completely ridiculous; it’s surreal and nonsensical and even a little Lynchian, and just as weird as giving a screaming kid a Schlitz because they love the taste of bitter. It’s like the video of that little kid whose mother asks them to say the words DUMP TRUCK and it comes out DUMB FUCK over and over again. It’s funny precisely because no child that age knows what DUMB FUCK means in the way that no toddler knows why singing a drinking song will make her grandfather laugh until he cries.

There’s a long time in me between knowing and telling, wrote Grace Paley.

I read this quote to my students all the time; I want them to understand that part of the writing process involves rumination and the knowing that precedes the telling. The fact that we have to grok the truth about something at the most visceral of levels before we’re able to make sense of it on the page, even if the process of creation itself is an unfolding and a revealing that happens like the unfurling of a lotus. I’ve been spending a lot of time — five years? ten years? — thinking about the roots of alcohol in my life, and have been warned against writing about it until I’m safely on the other side of the knotted relationship, with some contiguous time under my belt. Last week, I spent four days in a recording studio in Manhattan, taping the audio book for my second memoir, Treyf, which came out in 2015. There’s a fair amount of sex in it (for me; I generally don’t write about sex because I believe that it is for the most part ineffable, requiring negative space and narrative restraint which in turn results in no small amount of heat; less is almost always more) and there’s a lot of alcohol in it. I hadn’t read Treyf since its publication, and I was stunned to see booze everywhere just as it was in Motherland; the book is about growing up in an assimilated family in the sixties and seventies in New York, and there was, in fact, booze absolutely everywhere almost all the time. It made one cultured and erudite, accepted and normal, and, in some circumstances, gutted by shame. And, in my case, it also made me funny from the earliest possible days, long before I knew what it was, or was even drinking it.

A few years ago, I came upon a 1981 photo of myself with some high school friends on our way to a graduation party in Fishkill, New York. I remember the day well; I can even tell you that the long-sleeved orange tee shirt I was wearing came from a surf shop in Vero Beach, Florida, where my father and I had been a few months earlier during spring break. I was wearing Adidas white and red-striped soccer shorts, and leather Nikes. There is evident relief in the photo: we all knew where we were going to college. Graduation was a few days away. We all sit together in this photo, our futures ahead of us, plastic cups held aloft; I am certain that what is in my cup is not Fresca. We were all mostly good kids, Arista members and theater geeks and tennis players — none of us had gotten into much trouble in high school — but in no other photo of me taken at that time am I as happy, obviously laughing, and fitting right in, which is something I rarely did unless there was not-Fresca involved.

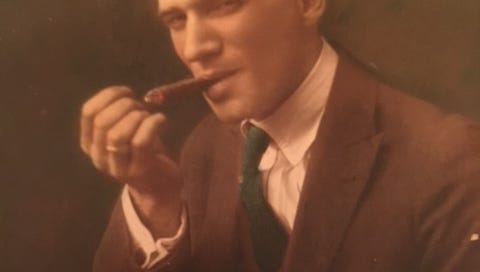

Recently, my mother told me that her father, the man to whom I sang The Souse Family, never drank, except medicinally. He suffered from terrible thyroid disease and was very thin for most of his life, and was always freezing; in the mornings before he left for work and my mother went to school, my grandmother poured him a shot of whiskey, which he drank with his coffee. My grandmother was a teetotaler, but she was a woman of her time, born in 1901, and she honestly believed this would stimulate my grandfather’s appetite, and also keep him warm; it did neither, and when he died in the late nineteen sixties, he was skin and bones, an orange-sized adenocarcinoma lodged in his left lung from seventy years of smoking anything he could light up: Camel Unfiltereds, Lucky Strikes, cheap cigars, a pipe. But drink? Beyond the thimble-full of whiskey, never.

The last time I saw him, my father told me to sing him The Souse Family, and I did, and Grandpa Phil threw his head back and laughed hard, his eyes closed, tears streaming down his face. I was a baby, and the song meant nothing to me except for its ability to make my beloved grandfather laugh until his sides ached and he reached into his back pocket for his handkerchief; it would be years before I’d understand the truth, and that it actually wasn’t funny at all. Not even a little.

Ooh, I have a picture like that one of you and your friends. And my uncle gave me beer at 10; my mother gave me bourbon and percocet at 13 for menstrual cramps. I didn't have a drinking song like that, but I sure did feel better with a drink in my hand. Yeah, none of it is funny but it is the truth. Knowing and telling. I'm sure that reading back through Treyf brought lots of knowing. It's true that there is space between knowing and telling. But sometimes telling helps with the knowing, maybe helps with the process of getting to the other side.

I will never tire of you peeling back the layers on your family. Ever interesting and nuanced and filled with devotion and story and love. In your words, it's all beautiful--even the hard parts.