the notebook on my desk

On Journals, Perfectionism, and Creative Clarity

Claire Messud writes by hand on graph paper.

Dani Shapiro once told me that she begins new work longhand because early drafts should not look like finished, polished manuscripts. And Lydia Davis writes every story in a notebook because there, nothing has to be “permanent or good.”

And yes: “You can’t write well — you can’t do anything well — if you feel cornered.”

True.

I was a stutterer as a child, a survivor of well-intentioned perfectionism. I struggled to get the words just right; it was expected in my home, and if I couldn’t unravel what I was trying to say on the watches of the people around me, I was often interrupted and the conversation was over. (Oddly, I still tend to attract chronic interrupters in my life, some kind-hearted, some not.) I took early to the practice of keeping a notebook because it was the place where I was able to complete a thought in whatever circuitous route I needed and had to. I also wrote stories and created lists and made feeble attempts at horrendous metric poetry. Whatever I was doing in my notebook was my own business: I used it to explain the world around me, and to make sense of it.

To make sense of myself.

Notebooks are the viscera and the DNA of art-making; they are proof of life and human frailty behind our dodgy attempts at perfection.

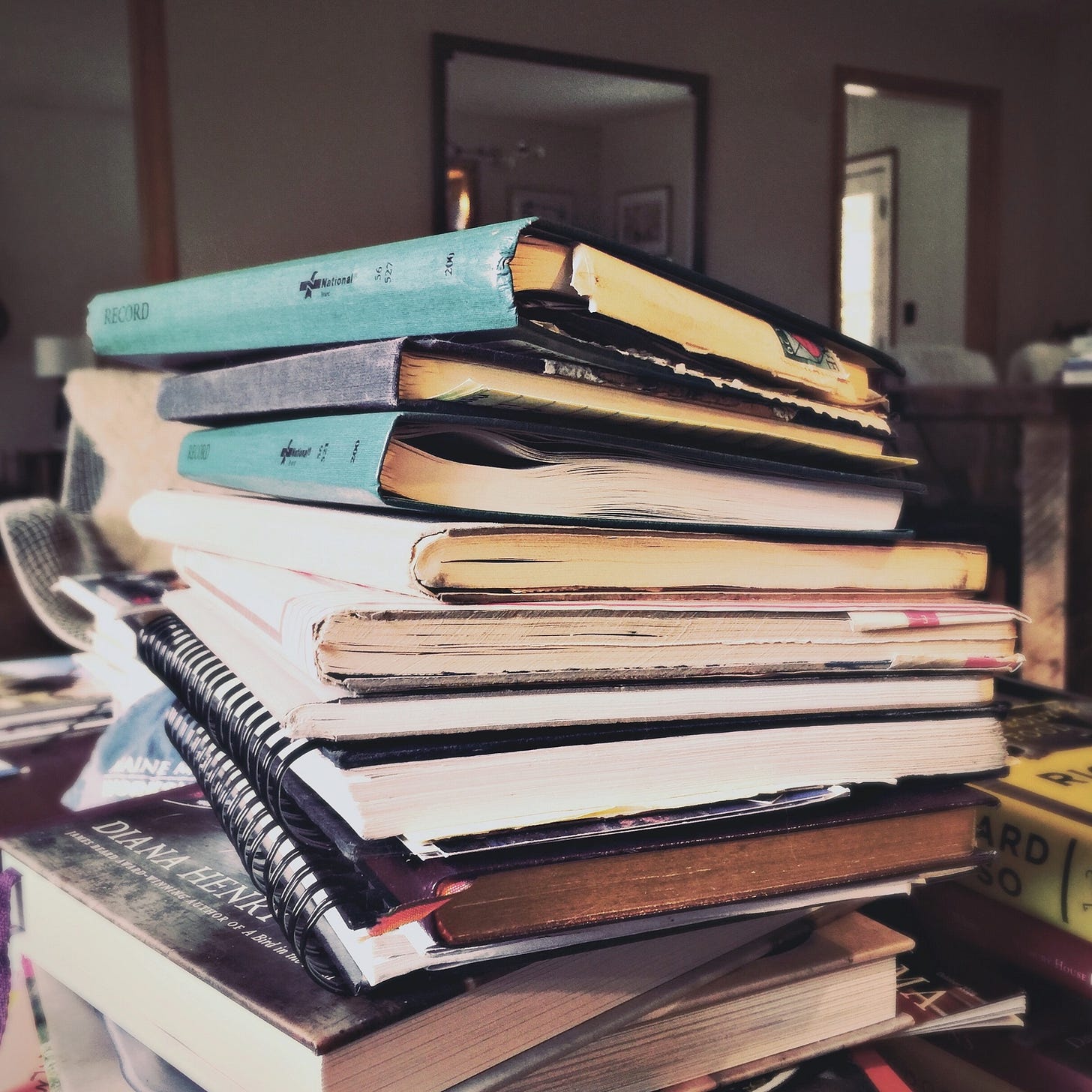

Eventually, the black and white hardcover notebooks of my 1970s childhood turned into better quality gray-covered lab notebooks. When I went away to college, I bought a stack of faux leather-bound notebooks at the old Harvard Coop, and wrote in those (one of them is still my kitchen notebook, stuffed since the early nineties with clipped recipes and notes about dinners I cooked for friends in my Manhattan studio apartment back in the nineties). Years later, Moleskines began to spawn around the office where I write and edit full-time now, in the home I share with my wife of twenty-three years.

The most important notebook of them all --- my father’s childhood three-ring binder, pebbled black leather, given to him by his beloved sister when he was a grade school student in the early 1930s --- sits on my desk at all times; I write notes for all of my books in it, in the earliest stages of the process. When the books are published, I clip together the notebook pages and store them together with the manuscript. This is neither posterity nor affectation: it just reflects my interest in the process — how I got from point A to B, what was going on in my life at the time I was writing, and how it affected my work, my voice, my day-to-day, my hope. The pages are interspersed with marginalia: lists, recipes, music I’m listening to, poetry. I have many artist friends who keep the same kind of notebook, be they painters, photographers, or singer-songwriters.

Perhaps this is a fetish understood only by writers and doodlers alike, that we would ascribe such importance to the container for early work in a manner that is as important to us as the finished work itself. An author friend once told me that the novelist Ruth Ozeki introduced her to the concept of keeping a process journal while she’s writing her books. I was mystified. Aren’t all notebooks process journals? Isn’t this why some of us are as compelled by the journals of everyone from Virginia Woolf and DaVinci to Annie Truitt, and Annie Dillard as we are by their actual art? Notebooks contain the stories behind the stories, even when they hold not a shred of evidence to be found in the end result. Notebooks are the viscera and the DNA of art-making; they are proof of life and human frailty behind our dodgy attempts at perfection —- that nasty, gnarly thing that Anne Lamott calls the voice of the oppressor.

Perhaps this is a fetish understood only by writers and doodlers alike, that we would ascribe such importance to the container for early work in a manner that is as important to us as the finished work itself.

Recently, I made the decision to make notebook-keeping a required component of my workshops and classes, as a kind of creative anchor, a tether that keeps one honest but also disconnected from the vagaries of the often hyper-competitive writing world. I used to know someone whose writing sharply mirrored whatever and whoever she was reading at the time: if a person in her life was having quantifiable success writing like Raymond Carver, she would try and write the same way not necessarily because she was creatively compelled to, but because her art-making was fueled by a competitive urge, an envious streak. It’s a common occurrence among makers of art, and anyone who says it is not isn’t telling the truth; our humanity comes with all sorts of hiccups and blips and quirks. It only becomes a problem when the competition and envy override one’s creative authenticity, which gets eclipsed by the weird, crave-y need to take what someone else has; it results in a lazy shadow of the other person’s work, and an emotional and practical disconnect from one’s own. Keeping a notebook disrupts this compulsion, and the competitive urge to write like anyone but oneself. It is, instead, a place to practice, to experiment, to fiddle, to excavate the truths that drive the words, with no one looking over our shoulder.

Although I ask my students to keep a working notebook, it is entirely their choice whether or not to share what they’ve created, and, if they do, to not share it with any specificity. Meaning: it is human nature to want to take a peek between the private covers, which is why exhibitions displaying journals and artist’s notebook are so very popular. (My favorite was Of Green Leaf, Bird, and Flower — a show displaying the journals of naturalists, which ran at the Yale Center for British Art some years ago.) But in the case of my students, I want to understand not what they are thinking, but how they are thinking, and how their behind-the-scenes might be informing their on-the-page process, or not.

As I come into the end zone on the writing of On Permission, I’ve looked closely at how permission-to-create touches every part of our lives be we working artists or not, and how every creative fear that we have might be diffused — or at least clarified — in the pages of a notebook. And this is why any of us makes art: to clarify our lives, to make sense of them, to understand the world around us and our place in it.

I am 65. I have kept notebooks and journals since January of 1971, when I was 13, when my very young teacher in his very first job in education, told us all to get notebooks and, "write. Just, write." He said not to worry about outlines, structure or spelling. He would check to see that we were doing this semester-long assignment, but we could get an A by just doing it, and any rewards we could reap were entirely up to us. I have been reaping the rewards of that first assignment for 52 years. Keeping journals gave me joy, an island of sanity in a world full of upheaval, and eventually a profession. I have crates and crates of notebooks and have new ideas all the time for more notebooks. Currently I have three going: My day-to-day journal, a meditation insight journal, a writing idea notebook. Often I don't even go back to read them, but they help me in the moment. Keeping notebooks is a process that is meaningful, perhaps, only to me, and when I die I imagine my burdened children can have one hell of a bonfire with all of them!

I just love this so much. I'm working on returning to note-taking and handwriting, practices that buoyed me as a child and got taken over by the efficiency of typing. I sometimes wonder what I lost when I replaced the art of writing in a notebook with the tendency to go toward Scrivener or my computer instead; slowly finding my way back. Thank you for sharing.