I would like to be one of those people who can haul herself up by the bootstraps and do the things that need doing with a minimum of sentimentality.

But I am my father’s daughter through and through, and we used to say that he cried at supermarket openings. That said, I went through a long period of stoicism born of a sheer reluctance to not give my mother the benefit of seeing me undone because, on the one hand, she liked to use it against me; she’d often laugh at my sadness and tell me to snap the fuck out of it, even when I was in single digits. On the other hand, vulnerability in the face of a narcissist never ends well because it has to be about them and only them. So for years, I dealt with my wobbles alone until I met Susan, another Cancerian, and then all bets were off and I became my father.

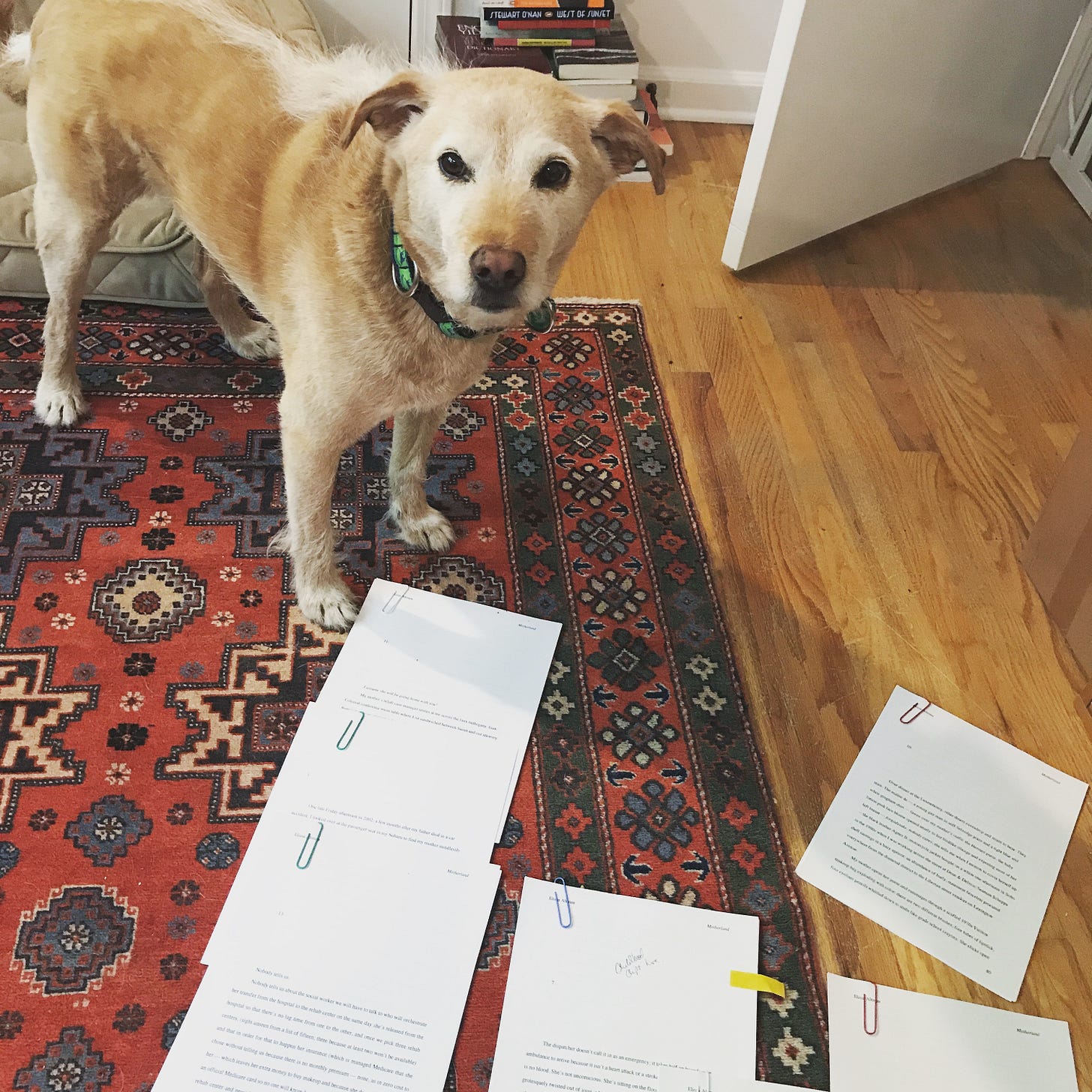

I remember reading somewhere that dog ownership is a contract with heartbreak. This is true; we know this going in. But I take issue with the word ownership; I don’t think of animals as possessions, and I never have. They’re not like a lamp, or a washing machine, or a car (although I know some people who would also qualify ownership of mid-eighties Volvos as a contract with heartbreak). When you bring a puppy into your life, it’s impossible to look ahead fourteen years. If you bring an older dog into your life, you can see the end zone staring you both in the face, and you know what you’re in for, but you do it anyway. We did the latter in 2009 when we adopted a seven-year-old, 106-pound yellow Labrador mix — a backyard breeder — from a gruesome high-kill situation in Paragould, Arkansas. It took a village to save her life and get her to us, and she was, soon enough, a full-fledged, opposable-thumbless member of our household who slipped into our routines like a hand in a glove. Not the least bit neurotic or destructive, in the first month she was with us she ate three remote controls in succession; six months later, we came home from work to find an unopened bottle of Navarro Pinot Noir and the cordless phone on her bed. We stood there, looking at her; she looked back, wagging. Despite her size, we could take Addie anywhere, and we did; she was that lovely.

He was scruffy and small, sort of a cross between an Irish terrier and a heeler, and in a short video sent to us by his foster mom, he, at two months old, appears to be attempting to hump a Dachshund, which says everything about him.

She also clearly needed the company of another dog, and having been bred twice a year from the time she was six months old, we knew that she loved puppies. The woman who fostered Addie for a month before sending her up to us discovered two pups dumped in a ditch near her Memphis home, scooped them up, got them vetted, and into a local foster. And then she called us one day to say she’d found a puppy for Addie, and was sending him north on a transport. He was scruffy and small, sort of a cross between an Irish terrier and a heeler, and in a short video sent to us by his foster mom, he, at two months old, appears to be attempting to hump a Dachshund, which says everything about him.

Just like that, we were a two-dog home, and when Pete arrived at three months old, we were faced with the anti-Addie: he didn’t smile or wag. A few months of living with her, though, and he was collecting cat toys from around the house and piling them up on her very tolerant Labrador head while waiting for us to make dinner. He was her foil; she was George Burns to his Gracie Allen. One night, after driving eight hours from Virginia back to our home, I left a breathtakingly expensive, unwrapped and salted Label Rouge chicken procured from a Virginia farm on our kitchen island, and went into the bedroom to change. When I came back into the kitchen, the chicken was gone, and so were the dogs. Being far too heavy to haul herself up to counter level, Addie had somehow communicated to Pete that it was his job to get the chicken and deposit it on the living room dog bed, where I found them standing side by side, their backs to me, licking the chicken and wagging. They knew that they were never going to get in trouble with us and that the odd bit of mischief was our reminder that they were actually dogs, and to put our chickens away.

It was evident that Pete was a very different kind of dog, and it was only after we lost Addie right before her fifteenth birthday that he came into his own. Like us, he grieved her loss fiercely and didn’t eat for two weeks. We worried for him, but he knew what to do: metabolize the fact that she was gone for however long it took, and then ease himself back into a different kind of life without her. We tried, repeatedly, to bring other dogs into the mix, but Pete was destined to be a solo dog, king of his castle, Grand Poobah, leader of the pack, and so popular in our neighborhood that people we didn’t know would walk past us every morning and say Hello Pete as though they’d already been introduced.

It’s not about tricks and blue ribbons and agility courses; it’s about the unspoken, quiet routines of living.

Despite his particular fondness for children — especially the unsocked feet of tiny babies — he could also be a total grump, as any terrier/herder can. He never snapped at or bit a soul, and never growled, but his side-eye was peerless. He was so smart that it frustrated him to not be able to speak in our language (at least this is what we believe), which led to a lot of loud and vigorous frustration barking. This only got louder as he got older and began to lose his hearing, which we think must have infuriated him; that aural first line of defense was so powerful in him that he could hear a pin drop in the next house. He barked when my phone pinged; he barked when the doorbell rang in a movie; he barked at the Amazon guy, the oil deliverer, the neighbors, and my mother, who he absolutely adored and who adored him right back.

A few years ago, I was a guest on John Bartlett’s wonderful podcast, Dog Save the People, and we talked about my mother and her lifelong love of dogs — at eighty-nine, she will cross a wide Manhattan avenue against oncoming traffic to say hello to a two-hundred-pound Newfoundland — and how, despite our acrimonious relationship and our emotional estrangement, it took Pete to get me to understand what it means to truly find compassion in my heart for her at the worst possible moments: he loved her purely and without condition or judgment.

About eighteen months ago, Pete began to cough. One vet thought that perhaps he had sudden allergies and an upper respiratory infection that wouldn’t break, and gave him a course of steroids, anti-inflammatories, and antibiotics. Almost simultaneously, he began to sundown: we were in Maine, in a cottage he knew and loved when he started to cry and whimper every night. Now completely deaf, he was panicking; he could no longer hear us, and he was crawling out of his skin. We became his human thundershirt, wrapping ourselves around him tightly every night until he calmed down. His hind legs began to give way, suddenly, and it took three more vets until a specialist told us what was happening: Pete did not have allergies. He had laryngeal paralysis, which went hand in hand with the degeneration of nerves in his hindquarters. He began to drag one of his back feet. (And then, if the planets lined up, he would run from the back of the house to the front like he was a baby again as if to say See, I can still do it, and then he would take a nap.) He tripped when he walked and was in such arthritic pain in his front legs — even medicated — that he cried while standing up, and he cried while sitting down. The cats would not leave his side as he coughed all night, every night, and struggled to breathe. All of us — cats, dog, humans — were awake for almost two weeks straight, as what was happening came into focus.

This is the part of the story where I grasp for words; some things are just ineffable. How does one write about something that cannot be codified, or organized? I think here of the words of Gail Caldwell, writing in Let’s Take the Long Way Home about her beloved Samoyed, Clementine:

Old dogs can be a regal sight. Their exuberance settles over the years into a seasoned nobility, their routines become as locked into yours as the quietest and kindest of marriages.

And this is it, isn’t it: the quiet. The negative space, in and of itself, tells the story of a relationship between two mammals who do not share a common language but are utterly devoted to each other. It’s the talking to a neighbor while your dog sits patiently at your side until he decides it’s time to get moving again, and he gently pokes at your dangling hand with his cold nose, and you both know what that means. It’s not about tricks and blue ribbons and agility courses; it’s about the unspoken, quiet routines of living, the assurance that food will be in the bowl and the kid will get off the schoolbus, and when you take out the cornflower blue harness, there will be a hike involved, even if it’s a short one. It’s about the magic in the mundane. There will be a bed (maybe yours) and the leather chair that he was never supposed to sit on but instantly claimed as his own, and the understanding that you will not own a single stick of furniture in the course of your lifetime that you will not share with your dog.

Last week, after two terrible nights, we made the decision for Pete, and I thank God that we live in a community where there is a vet who specializes in this, and — who ever knew there was such a thing — is also a chaplain. Because when you live for fourteen years with a creature who understands your every move and mood, who has devoted his life to watching over his home and its inhabitants, and who has reciprocated your profound love and respect for him, there should not ever be stainless steel tables and bright lights involved, if at all possible. Pete left this world in a quiet, gentle breath, surrounded by the people who loved him most, and his cats, and his things, and all the smells he knew. That he was chewing on his favorite dried cod chips to the last was a gift.

We walk around the silent, echoing house now; the cats are clinging to us. We’ve left the dog bowls out along with his beds, and small tufts of blond fur cling to the toys that we can’t bring ourselves to put away. We both swear that we’ve heard him in the night, tipping into the bathroom where we kept an extra bowl of water for him. We wake up thinking about our morning schedules and our early meetings and which one of us will take him for his first walk. And then we realize that he’s not here — that he lives in our hearts and our history now, the last connection to an earlier part of our lives together from back before the days of AARP cards and Medicare choices, of pandemics and retirement accounts and my being a caregiver, when we were, all of us, still young enough to race up Bald Mountain together in Maine.

I’ve come to accept the roles of sorrow and joy in my life — how connected they are, how one is simply the B side to the other. So yes, having a dog in your life is a contract with heartbreak. When I think of Pete, I think of the stolen chicken, and of him piling up cat toys on the head of his Labrador sister. I also think of the end days: the gasping, the sleepless nights, the legs that wouldn’t work anymore. And as hard as it was, it was our job to ease him out of this world with the knowledge that he was not alone, and that he was so very much loved and adored. I am my father’s daughter, and I have wept buckets over the last few days.

Many of you read my shorter posts about Pete and sent us kind messages; I read every one of them, and we are both intensely grateful for them. A few people wrote to say He was just a dog. And here I turn to Mary Oliver, writing about her Percy:

Emerson, I am trying to live, as you said we must, the examined life. But there are days I wish there was less in my head to examine, not to speak of the busy heart. How would it be to be Percy, I wonder, not thinking, not weighing anything, just running forward.

In memory of Petey Turner-Altman 2010-2024

Oh Elissa--this post destroyed me. I lost my soul-dog in 2018--and I do think she sent me Roxane shortly thereafter. I hope Pete is watching over you and Susan and the kitties and I am sending you so much love and as much comfort as I can.

Knowing that Petey lived his life with you is a comfort. I understand the silence. Communicating with Dublin is an honor. How does he know I have become old enough to lean on him to guide me safely down the stairs? I hope you both find solace walking by the sea. I am glad you are crying. It is your body learning how to live without Pete. We share your grief.