Perfectionism is a mean, frozen form of idealism, while messes are the artist’s true friend. - Anne Lamott

I admit to being the world’s worst artist. Or at least just hideously bad.

I started early: as a child, I was always drawing outside the lines in the coloring books my grandmother bought me. My people (and dogs and cats) were stick figures; now, in my fifties, they still are. I try, very hard, to make them charming and whimsical and artistically idiosyncratic, like Maira Kalman’s characters or Roz Chast’s, but in truth, they’re flat and boring and I can’t bear to look at them.

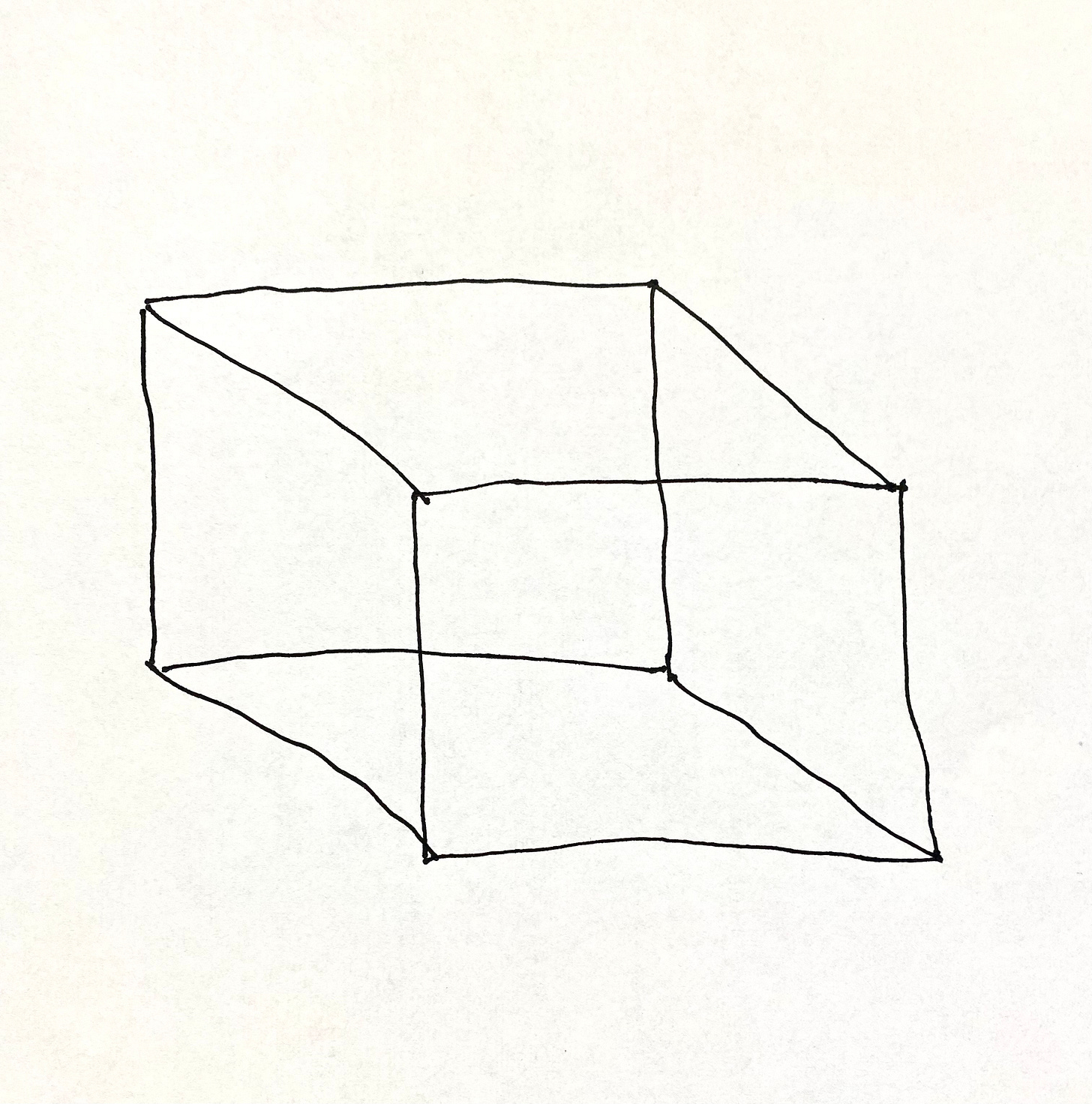

The only thing I can draw is a perfect, three-dimensional box. I have been drawing this perfect, three-dimensional box since I was nine years old, when my cousin Nina — a brilliant painter and charcoal artist — sat me down during a family dinner and said May I show you how to draw something? I loved, and still love her, and she took out a fine black felt tip pen, and drew a perfect box on a cocktail napkin.

Now you, she said, handing me the pen and turning the napkin over.

It was like magic, and I was astonished.

Perfect! she said, and I was thrilled.

I have been drawing it ever since: I drew it in my school notebooks, in my high school loose leaf binder, in my college notebooks, on legal pads at my editorial job when I got bored, on napkins during bad blind dates, waiting to be selected for jury duty, waiting at the DMV, waiting in a hospital gown for an MRI. It’s my go-to, my crutch, my security blanket. Also, it’s a box, and boxes by their nature keep things neat and tidy and contained, instead of a mess, like the bleeding watercolors I try to paint every year when we go to Maine on vacation.

Some years ago, Susan and I invited a friend and his two young kids to visit us while we were in a rental cottage in the swampy part of Maine that no one ever talks about, but whose emblem should be the black fly. He was going through a divorce, and so we thought we’d spend time together going to the beach and getting ourselves badly beaten at Monopoly by the younger kid, who, at the age of six, appeared to have all the makings of a real estate shark. Simon, like Susan, is a book designer, and an incredible illustrator and painter, so one early evening over cocktails and cheese curls, I asked him to teach me how to make some remedial watercolor paintings. I’d brought a quaint little set of paints with me, and some special watercolor paper, and together, the five of us – me, Susan, Simon, and Simon’s two kids – set ourselves up on the screened-in porch amidst the fly carcasses and the mosquitos as the sun was just beginning to dip, and Simon gave us a rudimentary lesson.

The kids produced paintings that were decidedly kid-like, but it didn’t matter. Simon proclaimed them excellent starts, and the kids, now bored, went into the cottage to read. Susan painted a vibrantly colored landscape, and Simon’s little painting was suitable for framing. My painting was disastrous -- like Mark Rothko on bad ayahuasca – because I had no sense of how watercolors work: they bleed, they flow, they’re completely uncontrollable and unpredictable unless you’re either a master, or your comfortable with surprise.

Wow, said Simon, looking at my painting. That’s so interesting –

Simon is a Quaker, and very well-mannered. And patient.

That’s great for a start, said Susan, looking over my shoulder.

And then we went into the cottage and made dinner.

I decided, right then and there, that it was over for me; I was embarrassed. I was ashamed. I’d never pick up a paintbrush again if I couldn’t make something that wasn’t good. I would never be one of those tall, spindly women who sets up her ancient easel on a bluff over the pounding Atlantic, wearing a straw hat and Chapstick and threadbare khakis. I was giving up on the spot because not only wasn’t my painting perfect; it was terrible.

There is no room for skill-building, for learning, for riding a bike with training wheels and experiencing that moment of sheer delight when they’re removed.

That was the first time I’d ever picked up a paintbrush, and – five years later – I am hooked — addicted — to painting shitty watercolors of my favorite place on earth: Maine. I show them to no one else but my wife, and rarely then, because they are messy, and I was taught: messes are the sign of a confused, distracted, undisciplined mind. Messes are the sign of a secret mental illness, an unraveling of thought, a psychosocial disorder. One imagines hoarders: The Collyer Brothers.

Nobody likes messes.

But the problem with this idea – with the sense that everything that every human produces in whatever form it comes needs to be out-of-the-gate perfect be it a loaf of sourdough bread or a watercolor painting or a popsicle stick box or a piano concerto – is that it means there is no room for skill-building, for learning, for riding a bike with training wheels and experiencing that moment of sheer delight when they’re removed. It leaves no place for accomplishment, and no sense of the joy that comes with it, whether it’s toilet training a toddler, or crafting an essay or writing a novel or driving a golf ball long and straight after hitting fifty slices in a row. The problems of perfectionism run roughshod over our lives everywhere from the boardroom to the bedroom (forgive me for saying, but if you can’t laugh in the bedroom, you’re screwed, or at least sunk) in the most public and private of ways. So what do you do? You draw the box — the thing that keeps things tidy and contained and predictable. Ho hum.

This is where the joy is, where the skill-building is, where the soul and spirit of work live, where the art and beauty are. This is the opposite of perfectionism.

We live in a world of instant expertise. I remember a few years ago being in the city one day and popping into the New York Road Runner’s Center — these are the people who run (literally and figuratively) the New York City Marathon every year. I’m no runner — actually, I am; just a shitty one. I run like I paint — but I have been a supporter of the Marathon since the eighties, and I wanted to see what the center was all about. I walked in and bopped around the little shop where one can buy NYRR tee shirts and jackets, and there it was: a jacket that was emblazoned across its back with the word FINISHER. There were NYRR tee shirts plastered with the word COACH from shoulder to shoulder. I was incensed. I know a lot of people who run the New York City Marathon (and the Boston, and the LA, and the Chicago, and the Berlin) and here’s the thing about running 26.2 miles: you have to be obsessed or crazy or both. It is other-worldly challenging. People die doing this. But any non-running schlub like me can walk into the NYRR Center, plunk down their credit card, and walk out with a jacket that makes everyone think they’ve finished one of the hardest races in the world that involves months of grueling training and the probable loss of one’s toenails, even though they might be winded dragging their garbage can out to the street every Wednesday morning.

You get what I’m saying.

Where is the sense of accomplishment? Where is the quiet bit of joy you feel when you run an extra mile on the treadmill and suddenly, you understand what runners love about it? It doesn’t exist when you buy instant expertise and perfection. As a teacher of writing, I often have to explain to my students why rejection is part of the process — after three, soon-to-be-four books, I could wallpaper my studio with the rejection letters I’ve gotten, some of them written by unpaid college interns who got the summer job through a connection — and it often unravels them. They’ve written something great that they’re proud of (and should be), and yet: it’s not right for The New Yorker or The Paris Review or goddammit not even a small, hip literary review that is calling for submissions. And I get to tell them: keep going, keep building, keep moving forward. Your work will never be done. As a particularly wise longtime student/friend of mine is fond of saying: remember the line in the Bhagavad Gita about not being attached to the results of your work. It’s the work itself. It’s the journey. I try and remind myself of this when my little watercolor paintings end up looking like the Rorschach tests of Ted Bundy, and I go back to drawing my perfect little boxes.

But the process is where the joy is, where the skill-building is, where the soul and spirit of work live, where the art-making comes from. This is the opposite of perfectionism, of instant expertise, and you can’t buy it, and you should never be able to.

[RECIPE]

Laurie Colwin’s Bloomer Loaf

Years ago, when I moved into my tiny studio apartment on East 57th Street, I decided that it was time to learn how to make bread. I had a tiny twenty-four inch stove which, when you opened its door, hit the edge of the kitchen table; if you opened the door to the tiny eighteen-inch dishwasher, you couldn’t get to the stove; if you opened the refrigerator door, you couldn’t get to the sink. And yet: it was my tiny kitchen and it was the early nineties, homemade bread was becoming very much a thing, and I decided that it was time for me to learn how to do it, even though earlier attempts had resulted in thick, un-risen frisbees of baked dough that were probably like the hardtack eaten by soldiers on the fields of Gettysburg.

I went out and bought every bread book I could find: The Tassajara Bread Book, Bernard Clayton’s Breads, The Book of Bread by Judith and Evan Jones. And I failed at pretty much everything I tried. Then I made Laurie Colwin’s bloomer loaf, which she adapted from Elizabeth David’s English Bread and Yeast Cookery. Laurie was decidedly blase about the instructions, which reassured me. I made it over and over, until I realized: I was actually making myself loaves of bread. And while they were not Poilane-perfect, they were good, and that was fine with me.

A bloomer loaf is a wonderful bread to learn on. It’s extremely forgiving and not at all cranky, it can sit for short or longer periods of time (much like me, in meditation) and is therefore ideal for busy lay schedules. The result is a baton-shaped loaf, slashed diagonally across its top. It makes wonderful toast — rub a hot slice of Bloomer bread with a raw clove of garlic and drizzle it with olive oil and pinch of flakey salt — and will fill your kitchen with mouthwatering aromas.

Makes 1 loaf

1-1/2 cups unbleached white flour, plus more for dusting

1-1/2 cups stone ground whole wheat flour

¾ cup whole wheat flour

1 tablespoon corn meal

1 teaspoon sea salt

1/2 teaspoon dry yeast

1-1/2 cups warm water (or 1-1/2 cups milk, or a combination of the two)

In a large bowl, mix together the flours, corn meal, and salt, and set aside.

Mix the yeast into the liquid, and let rest for five minutes, until it begins to bloom.

Make a well in the center of the flours, and pour in the liquid, blending it well. The dough should begin to come together, and should be neither overly sticky nor dry; if it is too sticky, sprinkle in a little additional flour, a teaspoon at a time.

Turn the dough out onto a floured cutting board, and knead it well for eight minutes, pushing and pulling it, folding the ends over each other, turning it ninety degrees, and repeating. Roll it in flour, place it in a warm bowl, cover it lightly with a clean linen kitchen table, put it aside, and let it rest and rise for a few hours.

Turn it out onto a floured board, punch the dough down, knead it for another five minutes, shape it into a baton (or a baguette), slash the top with four diagonal cuts, brush with a little water, and let it rest again for ten minutes.

While the dough is resting, preheat your oven to 450 degrees F. Place the dough on a lightly oiled baking sheet or a pizza stone, and bake for half an hour. Reduce the heat to 425 degrees F and continue to bake for another twenty minutes. The finished bread should have a hollow thunking sound when tapped on its bottom.

Let the loaf cool on a rack, before serving with softened sweet butter, and a small bowl of flakey sea salt.

Love this, Elissa

What a wonderful essay. I too learned to draw that box and also a horse head that is perfect every time. (I could show you!) I was bedeviled by perception for a long time, too. Everything you say is true and learning the hard way is often the only way.;)