I’m going to ask a question right at the top of this essay: how many of you have had family pieces — the things you grew up with and perhaps loved, or maybe didn’t but were still touched by — go astray after their owner died? And you find yourself in a quandary: do you ask about their whereabouts, or do you just let it go?

I have been accused of being sentimental, and I agree: I am. So was my father. He was an easy crier; so am I.

We were all fond of saying that he cried at supermarket openings; so do I. Myriad therapists explained this to both of us: my father, who died in 2002 after a car accident, lived much of his life with unresolved trauma stemming from a temporary abandonment by his mother in the mid-1920s (she ultimately came back and although she was a doting mother, she was made a pariah, and nobody ever bothered asking why she left in the first place), and also from intergenerational trauma (his grandmother was murdered by Nazis in Ukraine in 1942). I grew up in an acrimonious household, the only child of two people who intensely disliked each other and each other’s families. I lived with and survived physical, emotional, and sexual abuse that resulted in my wearing a kind of invisible chainmail until it grew too heavy to shlep around, like Marley’s chains; when I began taking it off, piece by piece, it clattered to the ground and exposed my sorrow-filled, wine-drenched heart to the sun and grew spotty patches of peace in its place. The same thing happened to my father, but only after he divorced my mother, and was able to express his despair openly and without fear of unkindness or reprisal, and he began to heal himself and find a love that would last for the rest of his life.

But the resultant sentimentality: it also brought with it an attachment to things that had belonged to people I loved who made me feel safe, and in some cases, to people I didn’t even know very well. My maternal grandmother’s locket; my father’s silver ID bracelet, bought for him by his parents when he left for the Navy during World War II. A pencil sketch of a child and her caregiver bought in Paris by my aunt in the 1960s; my father’s childhood leather looseleaf binder from 1930; his collection of 1950s jazz vinyl; the four Hirschfields he bought as a bachelor and that hung in my childhood living room. Shortly after he died, my stepmother gave me a book belonging to my father when he was in single digits and in sleepaway camp; it was called Mystery and Adventure Stories for Boys and is inscribed on the inside front cover by my paternal grandmother: Dear Seymour, Let me know when your [sic] finished and then I’ll send you another book. Love, Mother + Dad

Over the years, I’ve become fond of and partial to things that had once been beloved by others: I prefer older, vintage guitars to new; inscribed leather-bound books of poetry to new; chipped, pre-owned Le Creuset cookware; wooden spoons warped with time that belonged to my wife’s Aunt Millie (who I knew and adored). But somehow, with time, I’ve come to understand that so much has gone — disappeared into thin air, like it never existed — that I only realize it when I think to look for it, for specific occasions: my cantor grandfather’s multi-volume collection of Shakespeare, published in Yiddish. His six silver kiddish cups that I used to count in his Brooklyn bookcase when I was a child, each one inscribed with words that I couldn’t understand in a language that I couldn’t read, bequeathed to him by various organizations for his leadership and spiritual guidance. He died in 1976, and had my father inherited them from him (you’d think he might have inherited at least one or two of them if they were split between his ownership and my aunt’s), they would have been passed down to me, because I have no siblings.

But no; they’re gone. Were they sold in an estate sale? Given to my cousins? No idea.

I used to know someone who was The Disseminator of Things in her family: she decided who got The Things, and why. When her grandmother died — despite the fact that her own grief-stricken mother was still alive, along with her uncle — she entered her late grandmother’s house, packed up all the various heirlooms that had come over from Ireland going as far back as the 1880s, and doled them out to family members as she saw fit. If she liked this person more than that person, the former would get A Thing, and the latter — if she somehow felt that they didn’t deserve it in her estimation — nothing. Even if something had been earmarked for someone specific — noted in, say, a will, or a letter, or even a verbal promise — and she got to it first and she herself didn’t want it (and neither did her grown children), she would donate it somewhere important (a museum; a library) and have the family name proudly emblazoned on a plaque next to it, and, if it was particularly valuable, reap the benefits of a tax deduction.

I lived with abuse that resulted in my wearing a kind of invisible chainmail until it grew too heavy to shlep around, like Marley’s chains; when I began taking it off, piece by piece, it clattered to the ground and exposed my sorrow-filled, wine-drenched heart to the sun and grew spotty patches of peace in its place.

Some years ago, when my wife and I began to cobble together semblances of our own holidays — Susan was raised as a devout Catholic but neither of us is remotely formally religious — I spent an entire month looking for one of my grandfather’s kiddush cups to place on our Passover table. I had grown up spending every Passover at my aunt’s house and then my cousin’s, but after my father died, and after an emotionally violent estrangement, I was suddenly on my own. I chose to focus on the holiday as being representative of what freedom truly means for everyone of every faith, along with the concept of welcoming strangers to one’s table. So I searched for one of the kiddush cups; I called my stepmother, and she had none and could not recall seeing them after my grandmother died in 1990 and her apartment was emptied. I had lived in that apartment for almost two years, until 1992, and I don’t recall seeing them. Not one of them. Someone, somewhere along the line, had made the decision to take them; even though I was one of three grandchildren, it never occurred to anyone to ask me whether I wanted one as a way of remembering and celebrating the memory of my grandfather, who I had loved deeply.

Do the Things of One’s Ancestors possess such a level of importance as to represent history and love and the actual fact of one’s being and breath?

Eventually, I stopped looking, and just put a small French water glass on our Passover table, and prayed that no one would knock it over while reaching for the horseradish. Years later, during our annual trip to Maine, Susan and I stumbled upon a beautiful kiddush cup in an antique store specializing in silver; it bore the inscription 1924 Budapest. My maternal great grandparents both came to America from Budapest in the 1870s, and so I took it as a sign; we brought it home, and it has sat on our Passover table ever since. We imagine its history and wonder whether or not the family members of its owner ever think about it, and where it eventually wound up. I would be happy to talk to them, and if they asked for it back, I’d polish it well, and send it on its way.

What does it mean to be invisible in the eyes of The Disseminators? To not be important enough to receive The Things of One’s Ancestors, to be made to not exist, to never have existed at all, like the Jimmy Stewart character in It’s A Wonderful Life? To be removed from family slide shows and snipped out of photo albums? To be by-passed as though one is simply a specter, a flimsy figment of wobbly memory? Do Things — the Things of One’s Ancestors — possess such a level of importance as to represent history and love and the actual fact of one’s being and breath? Do they represent The Matriarchs and The Patriarchs, and what it means to be a part of family history?

Argue it away, but: they do. This is why when immigrants flee — war, starvation, or simply for a better future — they take with them the most important Things with the knowledge that they will be passed down, and the tribe, as it says in the Passover Haggadah, will survive.

Recipe

Tarte Tatin Matzo Brei

I generally prefer savory matzo brei made with caramelized onions and a lot of black pepper, but this version came from my late aunt, who made it a tradition to serve it to her grandchildren whenever they came for a visit. It became an edible family heirloom, passed down from generation to generation, not unlike the other Things of Our Ancestors.

Serves 4, in a perfect world

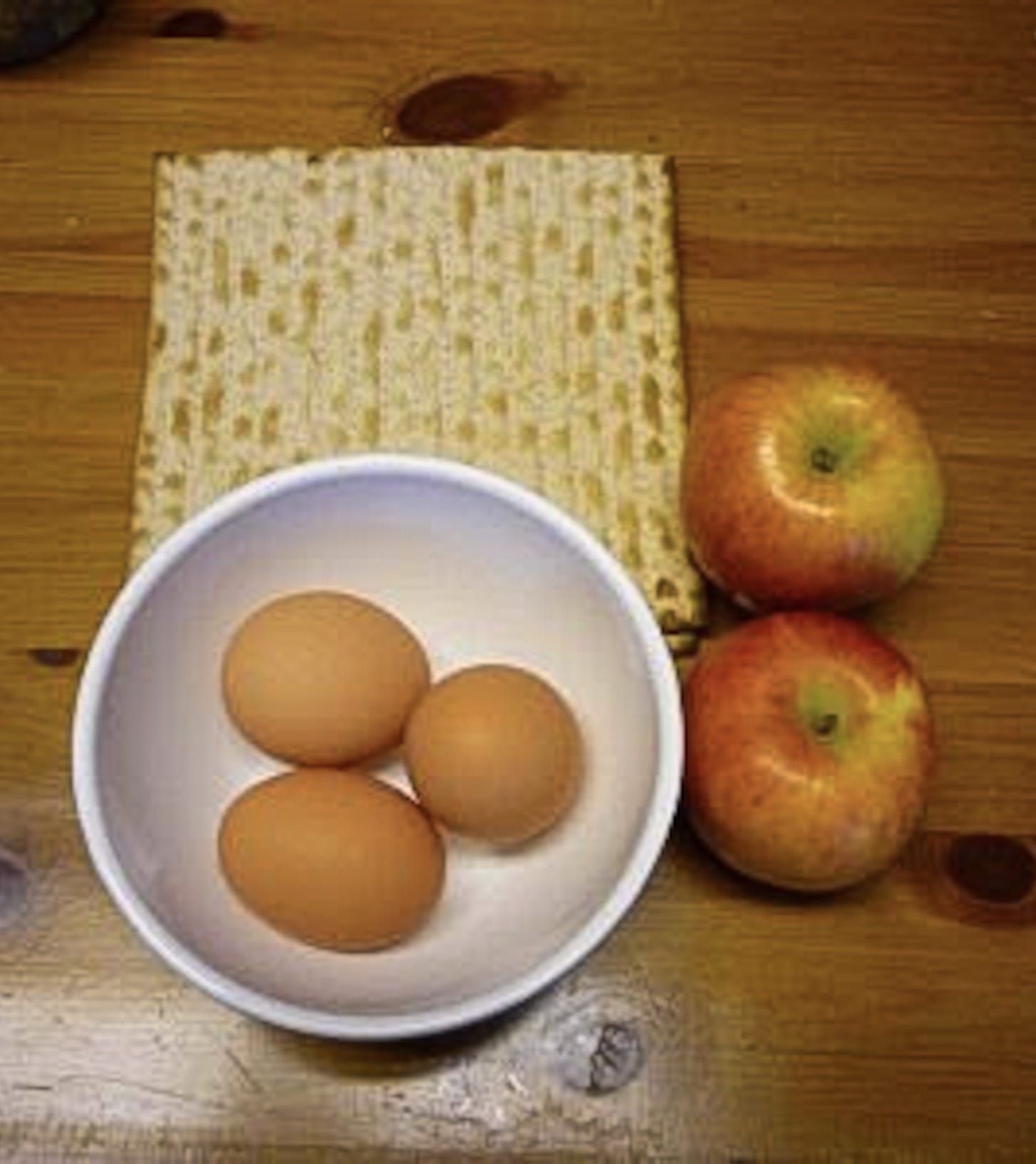

6 matzo boards

4 large eggs, beaten

2 Tablespoons unsalted butter

2 large apples, peeled, cored, and sliced thin

3 Tablespoons sugar

1 Teaspoons cinnamon

Note: if you are kosher, or keeping kosher for Passover, replace the butter with olive oil or non-dairy plant-based butter.

1. In a large bowl, crumble the matzo boards into the beaten eggs. Set aside.

2. In a large, stickproof skillet set over medium heat, melt the butter. When it begins to foam, add the apples to the pan, reduce heat to medium, and cook for 5 to 8 minutes, until they begin to soften. Sprinkle in the sugar and cinnamon, and continue to cook until the apples begin to caramelize.

3. Pour the matzo and egg mixture directly over the apples, and using a wooden spoon, distribute evenly. Cook for 5 minutes, until the egg mixture begins to pull away from the sides of the pan. Cover and continue to cook for another 8 minutes.

4. Remove the cover, and give the pan a few good shakes. Carefully place a large dinner plate or round platter over the skillet and invert its contents onto the plate; slide the brei back into the pan, apple-side up. Cover, and continue to cook for another 8 minutes.

Slice into wedges and serve directly out of the pan, with warm maple syrup.

I'm in the antique jewelry business- talismanic stuff. A story to share- A woman came into the shop with a very long, (maybe 4 feet), heavy 18k yellow gold chain. She wanted my shop to cut it and make 6 or 7 bracelets out of it. She shared that the chain had been sewn into the hem of the dress her great grandmother wore when emigrating to the US from Greece as a young widow with 3 small children. The chain was meant as insurance, a way to bribe people along the way as needed to insure safe passage. It remained intact, and my client had inherited this entire chain. To truly honor the family matriarch, this woman had enough jewelry made from the chain to give a piece of it to every one of her Yaya's female descendants. THAT'S how to do it!

I remember going to the 26th street flea market and looking at a seemingly untouched drawer full of little things, which reminded me of what someone might find when any of us die. A few years ago,after my mother’s death and the sad necessity of selling out funky but cool family home of 55 years,I had to be pretty ,well, practical, going back to a 600 sq. Foot walkup.I kept some things,and whenever they get touched,they bring back memories….but less is more. Someone is going to empty out My apartment some day.