I did not grow up with a Christmas cookie tradition, which was fine — I didn’t long for one; I had, and have, no sweet tooth.

We are Entenmann’s people for the most part, and even then, I’d almost always rather have a slice of pizza or a grilled cheese sandwich or even a little whitefish salad on a toasted sesame bagel from Tal’s. I come from a family whose men are known to hoard Mallomars during Mallomar season (September through March). And in the days of Mrs. Herbst Bakery in Manhattan, we would often double park on weekend nights, waiting for the bakers to take apple strudel out of the oven. What few Christmas cookies I ate were gingerbread, and procured from JayDee Bakery on Queens Boulevard in Forest Hills; I ate the frosting and the little silver balls, and gave the cookie to my grandmother. Actual Christmas cookies were alien to me and my experience until I met my wife almost a quarter of a century ago and moved in with her after a year of weekend trips back and forth from Manhattan to northern Connecticut. And I understand that they are a thing, and that people get very serious and even a little uptight about them, and now I understand why.

I remember years back, when Susan’s mother Helen was still with us, and her many siblings (who ranged from 80-100), nieces, nephews, and assorted other relatives would come to her house for Christmas, for a meal that Susan and I would cook: usually a whole fillet, always mashed potatoes, always green beans. The run up to dinner would be inevitably soused, for all of us: the older folks were hardcore vodka drinkers and by glass number three were fighting in a way that only family members can fight. There was a cousin who the rest of the family fooled by pouring Welch’s grape juice into a wine glass and mixing it with a tiny shot of vodka so he’d get some semblance of a buzz without being aware that he was not drinking Carlo Rossi. Inebriation is inebriation, and the Gods of Excess don’t know the difference between Two Buck Chuck and Petrus, and so we were frankly neither better, nor different: Susan and I kept the good wine — the Romanée-Conti and the Saint-Émilion — on a basement shelf behind the crockpot so that it wouldn’t be mistaken as a mixer for the Popov.

These pecan balls are like the Spanish Fly of Christmas cookies.

After the arguing and the plate-passing and the risk of Auntie Et removing her teeth had passed, the cookies would come out: there were the simple ones I recognized (sugar, thumbprint, glacé cherry) and the more complicated ones I did not. And sitting on Helen’s tiny round kitchen table below the plastic wall clock and the palm cross from the previous Easter were two cookbooks of the type assembled over time, in installments: there was one lone volume from a Women’s Day series, probably dating to the early Sixties or late Fifties, back in the day when all food photography turned out orange; and a massive collection of short cooking pamphlets (meats, appetizers, snacks and sandwiches, cakes, etc) of the kind a credit union might give you for opening a new account, or in exchange for a few sheets of S&H green stamps. And between the covers of these books: absolute baking gold.

When Helen died a few days short of her 95th birthday in 2014, we made sure we brought home the cookbooks with us.

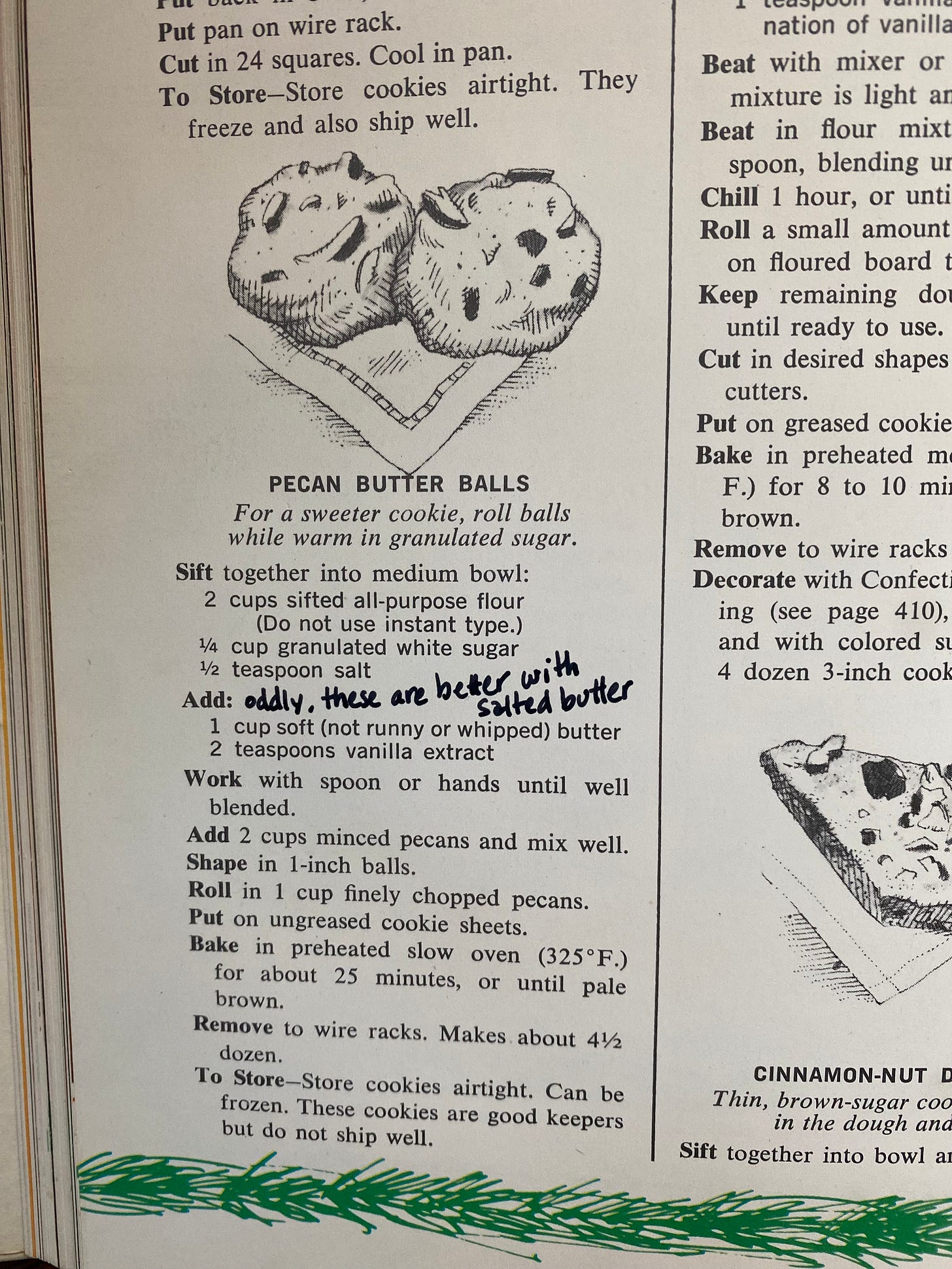

But this is the thing: nobody needs more cookie recipes. Most of them are family favorites; for example, my friend, the brilliant food writer and editor Susie Middleton, just wrote about her mother’s molasses crinkles. When the holidays arrive, Susan — who is an extraordinary baker: she’s a book designer by profession and measures things for a living, so all of her balls and biscuits end up being exactly the same size, whereas I could easily make one espresso truffle the size of a golfball and another the size of a grapefruit in the same batch — hauls out these cookbooks, I know that Helen’s pecan balls will be forthcoming. And when they are in the process of being baked, I can’t be in the house. I can’t work, can’t think straight, can’t focus on anything when the cloud of warm pecan, butter, sugar, and salt wafts down the hallway.

Because: these pecan balls are like the Spanish Fly of Christmas cookies. Strange things can happen when one nibbles on these cookies. The key here is that they are not overly sweet, and they are best made with salted butter, which provides a great counterpoint if you choose to roll the balls in granulated sugar (which you don’t have to do). We’ve never frozen them — they just don’t last that long in our house — and, as the recipe indicates, they don’t travel well because they’re given to easy crumbling. As in: they fall apart in your mouth. If your Christmas holiday includes a planned seduction (assuming you’ve got the energy, after the wrapping and the visiting and the cooking), this is the cookie for you.

When Helen Turner made these pecan balls, they were the only things that got her siblings and extended family to stop fighting. They are the only baked good that I look forward to, ever. I suppose Susan could make them all year long, but, like Mallomars, they are seasonal, and they need to stay that way.

Because some things are just that special.

Yum! I used to make these, but rolled them in powdered sugar. I always warned people not to inhale before opening their mouths to bite into the cookie, but there would always be the reckless soul who refused to listen and then coughed for an hour. I like the idea of the granulated sugar -- making today!

Omg, such a great memory. My mother made these cookies, called them Pecan Dainties, and always had a pecan half on the top. (She flattened the dough balls a bit first.) My Aunt Julie also made them, but rolled them in powdered sugar and called them snowballs. (That was too sweet for me.). I think that version are also known as Mexican wedding cookies. I may have to make them for our Christmas brunch for orphans on Monday.