A few weeks ago, I took possession of a beautiful, massive bookcase that was being sold by my friend, author Kerri Arsenault. Sitting in the hallway of her airy Revolutionary War-era Colonial in Connecticut, the bookcase looked fairly diminutive, even at eighty inches wide and sixty inches high. The truth of its size became apparent when Susan and I enlisted our neighbors, Steve and Melissa, to help us get it down our narrow hallway and into my office. The obvious: wood does not bend, unless you’re a luthier. Another set of hands was called, along with his nail-gun and pry bar with which he could remove the molding from around my office door, the door itself, and the door across the hall. Once the bookcase was in (stark white against Farrow & Ball Hague Blue walls; very nice), everyone left, and I was faced with an enormous number of books to organize and put away, along with journals dating back to 1976, and a red leather desk diary from 1991. At the time I used the diary, I was living in Brooklyn in my late paternal grandmother’s apartment, which my father assured me our family owned in perpetuity, New York City real estate rules of renter’s inheritance being what they were, and still are.

I’ve written about this apartment for years in essays and my books, because it took on the role of a primary character — a family member — in our lives, but also because it revealed the underside of my father and aunt’s relationship with grief: the day I moved in in late 1990, toting my red leather desk diary with me, I found all of my grandmother’s things exactly where they were when she died, as though she’d just gone out to run an errand. This was my first lesson in grief unharnessed and unprocessed: that it can be successfully ignored, at least for a while. It can also be inadvertently (or intentionally) foisted onto the shoulders of someone else to deal with, in the name of fear, impropriety, or shame. This was common during the post-Holocaust years—a kind of genetic coding, when survivors and the kin of survivors, generation after generation, put one foot in front of the other by never looking back at the horrors and trauma their families and culture had endured. But at a certain point, all of that forward movement, and all the ignoring and foisting onto someone else began to reveal hairline cracks in the veneer. In my family, unresolved grief resulted in perfectionism and, in the case of my father, a subtle rage buried beneath layers of extraordinary humor. That was my takeaway: if I was funny, all that grief both inherited and original would simply vaporize.

But it was ultimately a setup: I moved into the apartment where my father and aunt had been children in the early 1930s and 1940s, and where my grandmother had lived alone for fifteen years after my grandfather died in 1976, before she herself died there. My father and aunt could not cope with the loss of my grandmother at ninety-three, so they left all of her stuff where it sat, enshrined, as though she might return any minute; I didn’t know this until I tried to unpack my own things the evening I moved in, and had no place to put them. There’s another story here: my grandmother had left her children when they were very young, and they briefly wound up in an orphanage until she returned, so getting rid of her things was something they were neither willing nor planning to do; that would be left to someone else—a family outlier; it would anoint this particular person the problem — the needy one, the one who asked for too much, who required her grandmother’s things be removed to make room for her.

My father and aunt finally did remove my grandmother’s things under duress; they were not at all happy about it, and it was a big deal because no one ever made requests like this of senior family members. As a result, my father and I didn’t speak for almost three years. Still, I only unpacked my suitcase; my books remained in boxes piled up in the living room the entire time I lived there. The only book that didn’t stay packed, that sat on the desk I used in my father’s childhood bedroom, was my red leather desk diary from 1991. When I finally left eighteen months later, I carried it from my grandmother’s apartment in Brooklyn to my new apartment in Manhattan, to my first home in Connecticut, and then to this one, where I have now lived for twenty years.

This was my first lesson in grief unharnessed and unprocessed: that it can be successfully ignored, at least for a while.

I never opened it until last weekend, when I began to reorganize my office to accommodate my new bookcase. I went through it page by page: it was filled with nothing but appointments — work lunches with New Yorker advertising reps, assignment due dates, squash dates, therapy appointments, family birthdays, vacations. I flipped to the last page where a few stray Rolodex cards were stuck into the back flap of the datebook, along with a sealed business envelope addressed to “John” and “Jane” Doe at my grandmother’s apartment.

At first, I didn’t remember receiving the letter, even though it came from a lawyer’s office. I couldn't recall why I had stuffed it unopened into my datebook so many years ago, and then promptly forgot about it. I left it on my desk, and went on organizing my bookshelves. And then it came back to me, and that old familiar queasiness — the memory of instability, of What Ifs, of being told a fable by a man in deep denial who wanted to protect both of us from the problems of fact, and in doing so spun a tale that was not only untrue but that endangered me — returned.

I was “Jane Doe.” I was a name attached to a body with no discernible identity of her own beyond a fraying tether to her family’s unresolved grief.

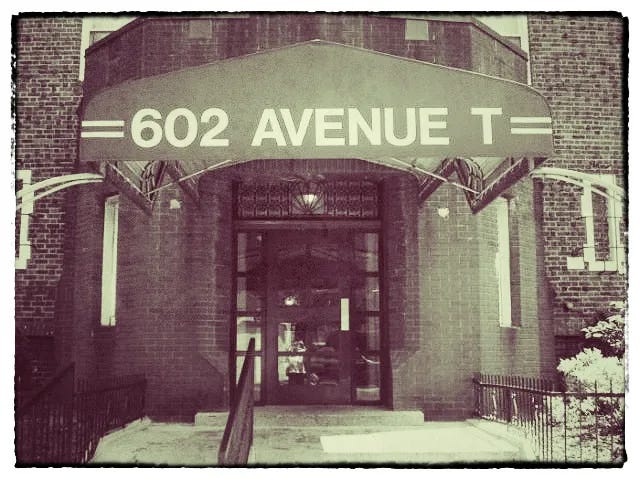

We own it in perpetuity, my father had said about our apartment at 602 Avenue T, but this was magical thinking. I had no reason not to believe him, until I began to see the same beat-up gray Chrysler Cordoba parked outside the building every morning, waiting for me to emerge. I was being followed by a private investigator; he was also following my father, who had moved in with his girlfriend in another, distant part of Brooklyn. Lawyers’ letters began to arrive at the apartment, shoved under my door at three in the morning, followed by frantic doorbell ringing. The letters were addressed to “John” and “Jane” Doe, and my father always instructed me to not open them; I could never understand why. Finally, after months of this, I did: the letters were demands to vacate and turn the apartment over to the landlord, who claimed that my father was in default of the third lease renewal dating to 1942, which made clear that we had to live in the apartment together for a full year before he could turn it over to me under New York State law. Until then, the landlord said that I was living in the space illegally. My father was furious not at the landlord’s demand or my harassment at the hands of a private investigator, but because, at twenty-eight, I had not obeyed him. I had opened one of the letters and discovered the truth that was being hidden from me and could no longer be ignored or fairytaled away.

I was at a turning point in my life. Raised in a traditional home where no one even dated outside our faith much less got involved with someone of the same sex, I had just left a secret relationship with a woman. I was between jobs. I was drinking massive quantities of cheap rotgut white wine every single night. I was alone: because the apartment was so far from Manhattan, I couldn’t see friends for dinner unless I wanted to sleep on someone’s couch, or stay with my mother. Dating was out of the question. Moving into the apartment gave me a place to live, but also made it possible for my father to keep it in the family: I was a single square peg meant for a single square hole. Back then, I moved through life like a pinball in a pinball machine, responding to external stimuli but never — not once — doing anything that might remotely be reflective of my own needs, my own safety, my own future, or any sort of self-actualization, because I had no self.

I was “Jane Doe.” I was a name attached to a body with no discernible identity of her own beyond a fraying tether to her family’s unresolved grief.

A few months before I left the Brooklyn apartment, my father and I were hauled into housing court for a third time, and I asked him, point blank, on the way there: did we own it, or did we not. He pulled the car over to the curb on Schermerhorn Street, and didn’t answer my question, but revealed to me his expectation: that I would live in the apartment, marry, raise a family there, and pass it on to my children, just as he was doing. There would be an Altman in that apartment, he said, forever. The fact that it was a rental and owned by a landlord, and the fact that we were being dragged into court under the threat of eviction, was irrelevant: the yoke of history was on my shoulders. I would be the tipping point. I had a choice: I would leave to take care of my own life, or I would fight the system as Jane Doe and keep the apartment in the family into the future.

In the spring of 1992, my mother and I together bought a studio apartment in east Midtown Manhattan, a seven minute walk from my office. The real estate market had bottomed out, the place was incredibly inexpensive, and it was an all-cash investment for us and a safe place for me to live. The night I moved into my new apartment in the city, I slept for eighteen hours: there was no threat of letters being stuffed under the door, or an investigator following me to and from the subway every day, or the doorbell ringing at three in the morning. I was no longer “Jane Doe.” I had my life back. But before I left my grandparents’ apartment, I had also stuffed the last letter we received into my datebook, and never opened it until last week, like it was a note buried in a time capsule.

Thirty-three years later, I am sixty years old, and together with my wife for almost twenty-five years. We have lived in our home for twenty of those years, and yet, I have an ever-present, persistent, always-there fear of losing the roof over our heads, of being harassed to get out by someone who doesn’t even know us. Over the years, I have driven my wife past 602 Avenue T, and have obsessively searched real estate listings for pictures of what the apartment looks like now, with its inevitable granite countertops and stainless steel appliances. I wonder if they’ve straightened out that annoying dip in the linoleum kitchen floor, and whether or not you can still sit on the floor beneath the breakfast room window, your back to the Coney Island parachute drop, toss a squash ball to the far end of the room, and have it roll back to you while you pour yourself another glass of cheap white wine, one cat on your left and one on your right, thinking about where you’ll all go when the boom comes down and the doorbell rings and they evict you in the middle of the night because they don’t give a shit whether Altmans were the first tenants there at the tail end of the Depression, or what your name is, or even if you have one: you’re Jane Doe.

I wrote in Motherland that safety and security are a myth; trouble can come from anywhere. It can come in the form of illness or addiction; it can come in the form of a middle-of-the-night letter delivery, or an attack; it can come as a father’s profound love for his daughter plaited together with a trauma so bone deep that it informs his every breath. There is no avoiding trouble in this life, no way no how, and when I remember the lost family home I fled as a nameless “Jane Doe” who torched her father’s dreams of continuity, I think of my wife who sits at her work desk as I write this, the mess of a garden, the barking dog, and the grocery list waiting for my attention, and the lines from the end of Mary Oliver’s Walking Home from Oak-Head:

Wherever else I live -

in music, in words,

in the fires of the heart,

I abide just as deeply

in this nameless, indivisible place,

this world,

which is falling apart now,

which is white and wild,

which is faithful beyond all our expressions of faith,

our deepest prayers.

Don't worry, sooner or later I'll be home.

Red-cheeked from the roused wind,

I'll stand in the doorway

stamping my boots and slapping my hands,

my shoulders

covered with stars.

Wow this is a powerful family drama — Dani Shapiro’s Family Secrets Podcast worthy. Since my former mother-in-law lives on Avenue Y, and since I’m also the granddaughter of a Holocaust escapee, and since your telling is so visual, I really experienced this story vividly.

Just wow!