Anyone who has written a memoir, or kept a journal, or both, likely knows this Joan Didion quote from Slouching Towards Bethlehem:

“...I think we are well-advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind's door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, whno betrayed them, who is going to make amends. We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were.”

As a writer of (mostly) memoir, I dig deep with my shit-stained psychic shovel, entering the weird and darkened alleys and closets, bedrooms and barrooms of my past, whether I want to or not. The other day, I found myself writing about a bar in the East Village called Phebe’s, which, some years ago, served very cheap beer and had ladies’ room stalls with no doors. (Not appreciated.) I also recently wrote about the last man I dated, back in the nineties — actually, we didn’t even really date — and the combustive consummation of a years-long office flirtation; it was very nice and that’s all it was, and I’m happy that he is my last boy-memory, because he’s a lovely man. I saw him a few years later when he showed up at the NYU squash courts where I was playing competitively. I was wearing a blue bandana wrapped around my head and he said I looked like Jackie Chan; I laughed and introduced him to my new girlfriend, who was watching me play.

Every once in a while, I think of an evening in 1987 at a cavernous restaurant called Canastels on Park Avenue South; I was with my mother and Buddy, my stepfather, with whom I was still living on the Upper West Side. I was wearing an extremely short (for me) mini-skirt and a purple short-sleeved sweater with massive shoulder pads, gray hose, and gray flats which were embellished with silver studs. I went to the ladies’ room, dodging a crowd of very tall women snorting lines of coke as far from the wall-hung bathroom hand dryer as possible (obviously; remember this scene in Annie Hall, even if you hate WA), came out, and two guys, financial types, who had been standing at the bar drinking Long Island Ice Teas, stopped me and asked if I wanted to go on a date with them. I said no thank you, and then pointed to my mother and Buddy, who was dabbing a spot of grease from an overcooked veal chop that had dripped onto his Hermès tie. The guys seemed deflated, like I’d said Oh sorry, can’t, Mommy is waiting for me. Which was actually true.

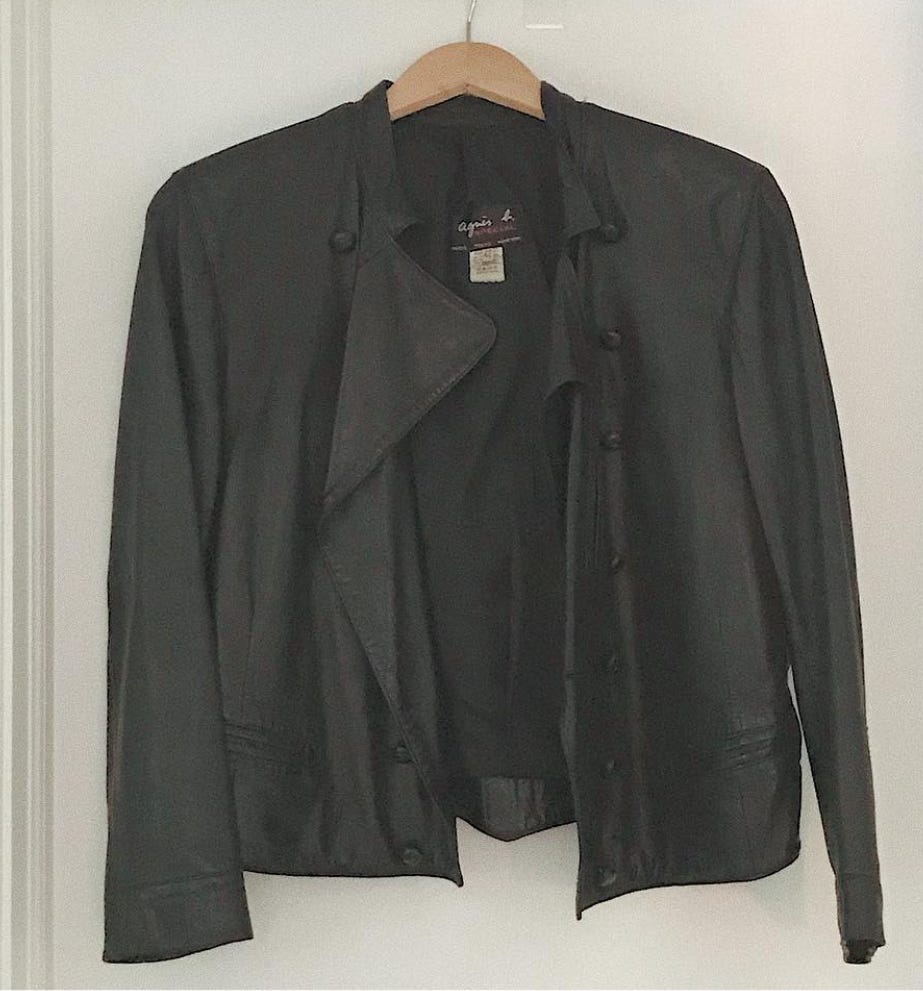

When I think about who I was at that time, it confuses me; I don’t know who I am now in relation to the person I was back then. There’s a disconnect, a gap; it’s as though someone snipped the line linking two different people. I see photos and they don’t compute. I do know that I was, very definitely, a clothes horse, whereas I am writing this while wearing the usual Breton shirt and sweatpants that I’m in on most days, and which are just this side of pajamas. Back then, my mother and Buddy were in the fashion world — he produced fur coats (I know) for Perry Ellis and Ralph Lauren and Louie Feraud — and I was absolutely attuned, sartorially, to what was happening around me; I was trained by my parents to be, from an early age. Eventually, after I moved out of their apartment and into a tiny walkup with a tiny roommate on the Upper East Side, I began spending a lot of time in the modern dance community, going at least three nights a week to City Center, or DTW, or the top floor of Westbeth, which was home to the Merce Cunningham Dance Company; I took to wearing black — a lot of black — and my hair was huge. When I went to work for Dean & Deluca in 1988, it was conveniently located across the street from agnès b. where, on a whim, my mother showed up one afternoon and bought me a staggeringly expensive leather jacket that I still have to this day, and cannot possibly part with: it has followed me to my late grandmother’s apartment in Brooklyn, my studio apartment on East 57th Street next door to Le Colonial; my wife’s little cape in Litchfield County, Connecticut; and here, where I write this, in Newtown, Connecticut. We pray that our last house will be in Maine (if the world doesn’t end before that), and if we can manage to pull it off between exorbitant real estate prices and my elderly mother, I will bring the agnès b. jacket with me, assuming I don’t move to Maine in an urn. The jacket will be forty years old by then, confirming that the only thing my mother and I have in common is that we get rid of nothing.

And this is a danger, isn’t it: my mother’s closets are filled with dresses from Morgane LeFay, which date back to the late eighties, along with outfits designed for her by Alik Singer, who had partnered with Buddy making furs. One day, I was sitting in their showroom on West 30th Street, and Alik showed up with a bunch of his patterns that had been rendered in lightweight cotton duck (which would then be used as the basis for his fur designs), and my mother took one of them — it had been marked up with wax crayon and various stitching here and there — and put it on, and Alik made her a suit based on it. It is still living in the recesses of her bedroom closet, along with a Perfecto motorcycle jacket that she stole from me in the early nineties, and boots and shoes that she hasn’t worn in almost a decade. She won’t get rid of them because they are an intrinsic part of who she once was, each thing marking a specific place and time in her life that she can recall vividly, even though she sometimes can’t tell day from night anymore. All that I have left from that period is my little agnès b. leather jacket, assorted mix tapes of Duran Duran given to me by my ex, and photos of a size 2 person with big hair and rubber gasket bracelets, who, if you squint, sort of resembles me.

The writing of memoir requires an ability to reach through the filters of time and be able to touch, hear, and see that person who resembles us and who was unaware, then, of who she might become. It’s a given that we’ll only get some of it right, because the passage of time and experience colors what we remember; it couldn’t not, and as Mary Karr says, memoir is the work of memory, not history. I have a synesthetic memory, like many memoirists, which means (for me) that I see the past in snapshots, in a synaptic tangle of the tactile and the olfactory; when I hear Hungry Like the Wolf on an eighties playlist, I smell the Tatiana perfume that my ex wore. When I re-organize my closet every year or so and take down the not one, but three Louis Vuitton bags that date from 1985, 1986, and 1988, the nubby coated canvas leaves the taste of cheap Soave Bolla in my mouth. The feel of my mother’s peach broadloom, now faded to white, that leads from her front door to the den where I lived for two years, conjures up the sound of David Dinkins’ voice on a small Sony Trinitron television, commenting on Robert Chambers’ murder of Jennifer Levin in Central Park, and a few years later, the creature who currently occupies the white house calling for the execution of The Central Park Five, for a crime they did not commit.

The writing of memoir requires an ability to reach through the filters of time and be able to touch, hear, and see that person who resembles us and who was unaware, then, of who she might become.

Who we once were transcends all the trappings of trend and place — they are only clues — although last night Susan and I were talking about our men’s overcoat phase in the eighties, which we lived through separately. Looking back, mine — a very large and long gray Herringbone Harris tweed single-breasted balmacaan, with its sleeves rolled up four or five times — was representative of the times themselves: there was money everywhere, and drugs in every bathroom, massive shoulder pads and massive hair, restaurants serving inedible vertical food on shiny black chargers the size of steering wheels, preppies slumming in Alphabet City, art and music and AIDS killing off an entire generation including so many of my friends in the food, fashion, and dance communities. I had moved from a slim French leather jacket to what was effectively a tweed tent, and a place to hide when the world turned ugly. My coat swallowed me up as though I was Jonah inside the whale; it was disproportionately voluminous and so heavy that I dragged it through my days like Marley’s chains. The world swirled around me — I didn’t like drugs, hated the noise and sharp elbows of the Limelight and Dancetaria, was disgusted by the politics of the time, and discovered that I liked women, a lot — and I wanted to disappear. And I did, both in my coat and in ways that were far less healthy than, for example, taking a a few days off. When I am overwhelmed, I know who that person in the overcoat was, and how she existed on a cocktail of fear.

Almost forty years ago, I didn’t know who I’d be now; I couldn’t possibly fathom it. How can we know these things? In those pictures, I’m almost always wearing (for me) a lot of makeup; these days, I can’t even get my lipstick to stay on for more than ten minutes. (Someone, please tell me.) In one photo, I’m wearing what appears to be a gold brocade double-breasted custom-tailored suit that looks like curtains torn from the windows of a Borscht Belt hotel dining room. I remember the texture of the fabric and how the shoulder pads made me look like Dick Butkus. But there’s nothing else: no memory of having bought that outfit, or why, or where I was going that night. If I had to write about how I came to own it, I couldn’t; I draw a blank. There is the memory of the feeling, though, and that still exists when I look at it: I’m unsmiling and glassy-eyed and looking vaguely like I’d swallowed a handful of quaaludes. I’m numb, wondering where I’d end up and with whom if I survived, and feeling like a live, anesthetized prop.

Some clothes are utilitarian, writes Charlie Porter in What Artists Wear. Some are sentimental. Some have to do with the community to which a person belongs, or wants to belong. My clothes — the gold brocade suit; the purple sweater with the shoulder pads; the Harris tweed overcoat — were not really any of those things, and when I write about them, I do so as though they were costumes dressing up a different persona. A me-not-me, who was looking for a way to anchor myself in a wild, unhinged time and place, hungry like the wolf, and flailing around like a toddler on ice skates.

The only thing, oddly, that tethered me was my little French leather jacket, perfect in its simplicity, which is infused with the story of who I was back then: the New Yorker, the size 2 food professional, the modern dance groupie, the caterer, the still-straight-gay-girl desperately trying to ignore the truth. Fashion is the armor to survive the reality of everyday life, said Bill Cunningham, and he was right. I’m sixty-one now, and as my life changes, so does the armor and the need to drag it like my overcoat through my days. But as I write this, wearing gray Glerup slippers and my Breton shirt and my sweatpants in the middle of the day, my leather jacket hanging in the guest room closet of the Connecticut house where I’ve lived with my wife for more than twenty years, I now understand why I can’t possibly get rid of it.

I keep bird feathers on my dresser top and old ideas in my closet. Our imagined selves never really leave us. At 72 I dress like an 8 year old at summer camp.

Thank you. I'm a memoirist/historian and love all things fashion--eh, rather, style. I now have the world's tiniest closet and love it. I can still remember my past through clothes--they are our armour and liberation, a way of "trying on selves." And yes, of remembering our selves.