I wrote last week about the tenth anniversary edition of my first memoir, Poor Man’s Feast, coming this year (I actually am going into the studio tomorrow in New York to record it) with a new introduction. Some of the things I talked about: who owns the right to tell a story? Is a secret really a secret if the writing parties don’t actually know it’s a secret? How much is the memoirist responsible for?

Shame is permission’s plasma.

In the first few pages of my upcoming book, On Permission, I talk about the toll the work of memoir can take on us physically, emotionally, spiritually. After Vivian Gornick’s memoir about her relationship with her mother, Fierce Attachments, was published, the author took to her bed. According to Mary Karr, Carolyn See famously collapsed with severe viral meningitis two hours after finishing the first draft of her memoir, Dreaming. See claimed it was her brain’s way of saying You’ve been looking where you shouldn’t. Honor Moore’s family vilified her to the New Yorker when the magazine published her essay about her father, Episcopal Bishop Paul Moore of New York City, and his bisexuality. Suzanne Lessard was sliced out of the Stanford White family --- he was her grandfather --- after she published The Architect of Desire, in which she revealed the sexual abuse perpetrated by her father not only on the author, but on her siblings as well. Filmmaker and novelist Ruth Ozeki writes in her stunning short memoir The Face: A Time Code about wanting to be good as a child, and knowing that being good meant being reserved and private. When Ozeki shows her Japanese parents her autobiographical documentary film Halving the Bones, she openly questions the reliability of memory and truth. Ozeki’s father asks her outright to never make a film about him; she gives him her word. She also changes her surname --- Ozeki is not her real last name --- to prevent family embarrassment, but to keep writing. Ozeki is not my father’s face nor my mother’s face….she says. Ozeki is my face, the face I chose, a nominal face that keeps them safe from me, and me safe from them.

To wait for permission to tell one’s story --- especially if one is a woman --- is to wait forever.

Writers are driven to tell their truths, and I speak here of moral value and the weight of judgement: if an author’s life is directly touched by a particular action or person, it is their story to tell. When memoirists move from silence into speech, they make new life and growth possible both for themselves and their readers. To wait for permission to tell one’s story --- especially if one is a woman --- is to wait forever.

Three years after Poor Man’s Feast (the memoir) was published, I wrote the following essay for Krista Tippett’s On Being blog, to unpack issues of permission, story ownership, creative ownership, and shame: shame is permission’s plasma. My excision from a large swath of my family when Poor Man’s Feast came out bore this essay, and the book that is coming from Godine in 2024. It has been my life’s greatest, most horrific heartbreak, and one that I never could have dreamt that I would experience. And yet: I had to tell my story.

My following essay was originally published at On Being:

Interviewer: You mentioned getting permission to write. Who gave it to you?

Morrison: No one. What I needed permission to do was succeed at it.

In a Fall 1993 Paris Review “The Art of Fiction” interview, Elissa Schappell spoke with Toni Morrison about the writing life. Morrison talked about writing while holding down a full-time job as an editor, writing with small children in the house, writing as a woman, writing as a woman of color, writing about controlling one’s own characters (and not), writing about sex (“It’s just not sexy enough”). Morrison talked also about the weapons of the weak: nagging, poison, gossip. And about permission to write, and permission to succeed at it.

I read those words and had a sticky, squirmy reaction: I felt the way I do when I stand back and witness the horror of someone else’s undoing. It’s a tight kink in the stomach; a hard walnut in the throat. We’ve all been there, haven’t we? We’ve seen the speaker who loses the words. The young actor who blanks out on stage. The musician who forgets the chords. The writer — the food writer, science writer, the academic, the novelist — blocked by fear. We wince. Who are they to even try? some whisper as we watch them tumble from their place.

When it comes our time, we become that person, naked on the stage: doubtful, panicky, assured by the nagging, the poison, the gossipy gremlin chatter over our shoulders, promising that we too, will most certainly, most definitely fail.

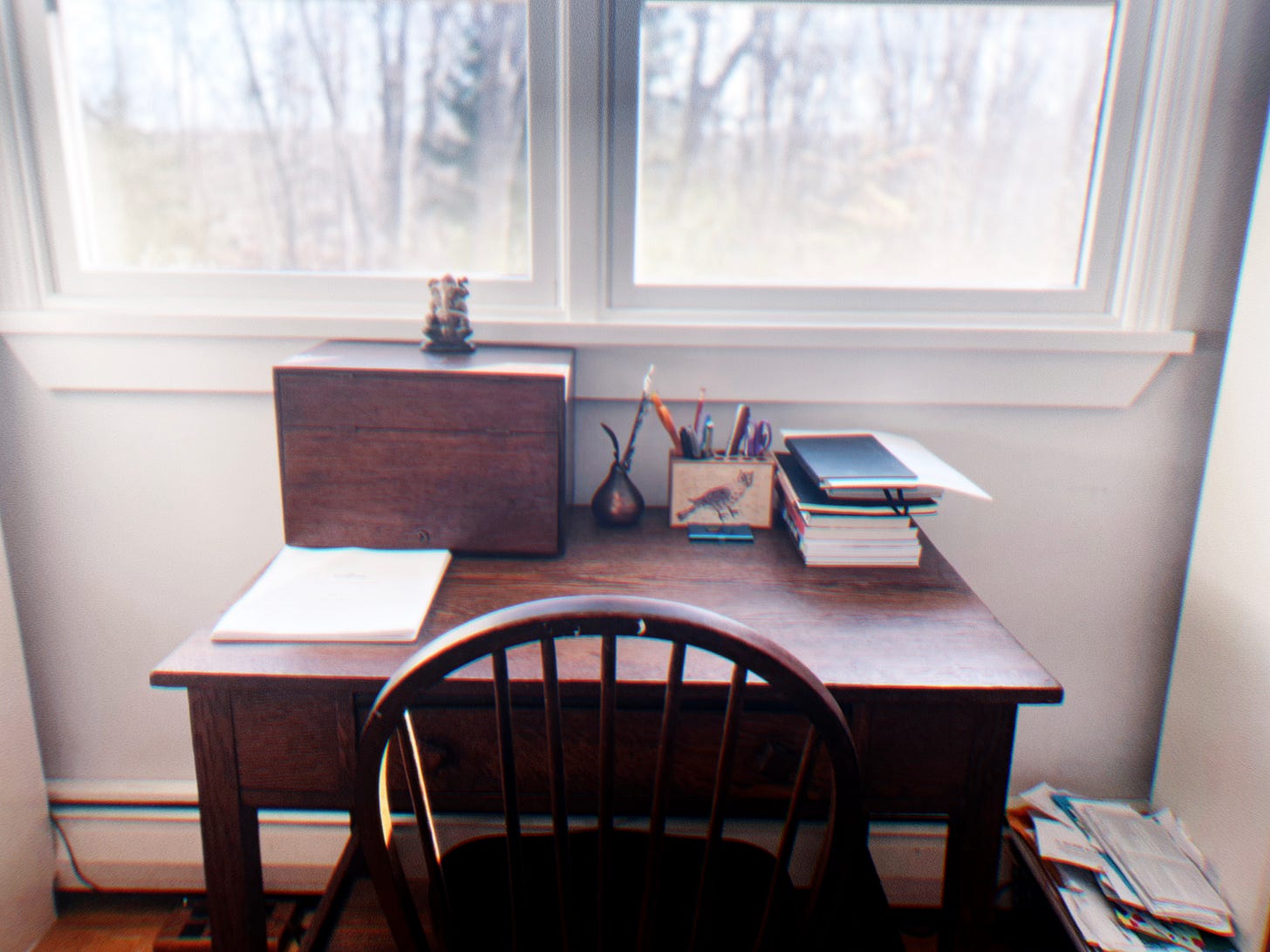

I have spent the last eighteen months writing a memoir. For a long while, I worked as a cookbook editor. I wrote on the train in longhand scribbles, at night in my pajamas, during lunch breaks, on the weekend, until it became clear to me that it I had to step away from one job or the other. After much hand-wringing, the decision was made: I relinquished my position tearfully. I loved it and was good at it — I had long ago been given permission to succeed at being an editor — and went home to my office and closed the door, and wrote.

When other forces say, no, that story is not yours, they have not only killed it and its place in your soul; they have killed you.

I did what all the books and my writing teachers say you’re supposed to do: I put my ass in my chair every morning at 8:30, and apart from doing yoga a few times a week, walking the dogs, and making myself endless cups of tea, I didn’t move. Some days the work flowed like a river. Some days I stared at the page — each word I managed to eke out was like squeezing the back end of an elephant through the eye of a needle — and wept. Alone. And I asked myself the same thing I asked while I was writing my first memoir.

Do I have the permission to succeed at this? Who am I to tell my stories?

“Who are you to not tell them?” a writer friend said to me. This writer friend — author of novels, memoirs, a short story collection — tells me that it is ownership, the acceptance of the fact that our stories make us who we are, that is the most complicated and treacherous part of what we do. When that ownership is withheld, we cannot succeed. When other forces say, no, that story is not yours, they have not only killed it and its place in your soul; they have killed you.

There are plenty of hurdles in the writing process: distraction, diligence, envy, arrogance, dedication, time, space, money, nagging, poison, gossip. There is the seductive conceit that lures you, like an animal into a trap, towards the belief that your work is spectacular, whatever that means, long before your work is actually done. There’s the quicksand of self-doubt so immobilizing that you can’t climb out of it, and the more you struggle, the deeper you get sucked in. Writing is balance. Mrs. Ramsay was right: A light here requires a shadow there.

The hurdles can make you think you’re better-or-worse-than. They can shut you down, prop you up, alter your course, tack your sails. They can result in moments of bliss and terror, calm and panic, hubris and humility, pomposity, paranoia, and paralysis. Often within moments of each other.

These obstacles may hinder permission to write, but they don’t withhold permission to succeed at it. The rickety, splintering plank connecting the two, as quavery as a rope bridge over a gorge, is reserved strictly for shame.

“You don’t think shame,” says Janna Malamud Smith. “You feel covered in its viscose grime. The great hand immerses you whenever you are told you are, or believe yourself to be, violating a basic communal code.”

To flout shame — to poke it in the eye — is to invite abandonment.

Truth: A well-known food writer tells me that no matter what she writes — her blog, her cookbooks, her endless articles — she is filled with paralyzing shame. “My mother,” she tells me, her eyes filling with tears, “is the family cook. I was supposed to be the lawyer.” When she won her first cookbook award, her mother asked, Who do you think you are? Every time the writer sets pen to paper, she is overcome with guilt and anguish. Every recipe is poisoned with the pang of resentment. “I will never be a success,” she says to me. “It would kill her.”

Truth: An artist in her fifties has devoted her life to creating bright, colorful pencil drawings. It’s a nice hobby, her elderly parents say, but your sister is the real artist. Why didn’t you become a teacher the way we hoped? Forever mired in disappointment — hers, theirs — her images are the same ones she drew when she was eleven, stuck in time and place, like their creator, longing for approval, waiting for permission.

Truth: A writer tells the story of something that happened to her late father almost a century earlier. The story, one of abandonment, is inherently cloaked in shame. Haunted by this myth, which feels almost Greek, this writer and her worldview have been molded and shaped by it since she was a child; it forever transforms her sense of safety and self. She writes her story and is expelled by her family, who has kept it a secret for nearly a hundred years. Who do you think you are to write about this? they say.

Malamud Smith writes:

“Shame is a group survival reflex in which the individual is an afterthought. Shame’s first goal is to have you confirm to group expectations. Art-making is a profound way people deal with shame. One way art transforms [it] is by replacing helplessness with agency.”

Like Morrison, we look beyond ourselves for the permission to succeed. This external yearning for that which is granted by someone or something else, something outside ourselves, is instilled in us from infancy and metabolized like mother’s milk. May I, can I, should I. To disregard it is to step into thicket and thorn. To flout shame, to poke it in the eye, is to invite abandonment. As writers and artists, we depend upon the external to feed us after our solitary days at work. To violate that compact feels like sure death. In truth, it is life.

Quiet the noise around you; soften its pitch. Our deepest stories are our best teachers. Let the weapons of the weak — the poison, the nagging, the gossip — burn themselves to ash. Cast them to the wind. Take back the permission to succeed, to tell your story.

Make it yours.

Elissa Altman, 2016

I can't wait for On Permission. That book is going to mean to much to so many people, and I know I'm one of them. Thank you.

Truth! Much needed permission here. Thank you.