It is true what they say: very often, writers write the books that they themselves need to read.

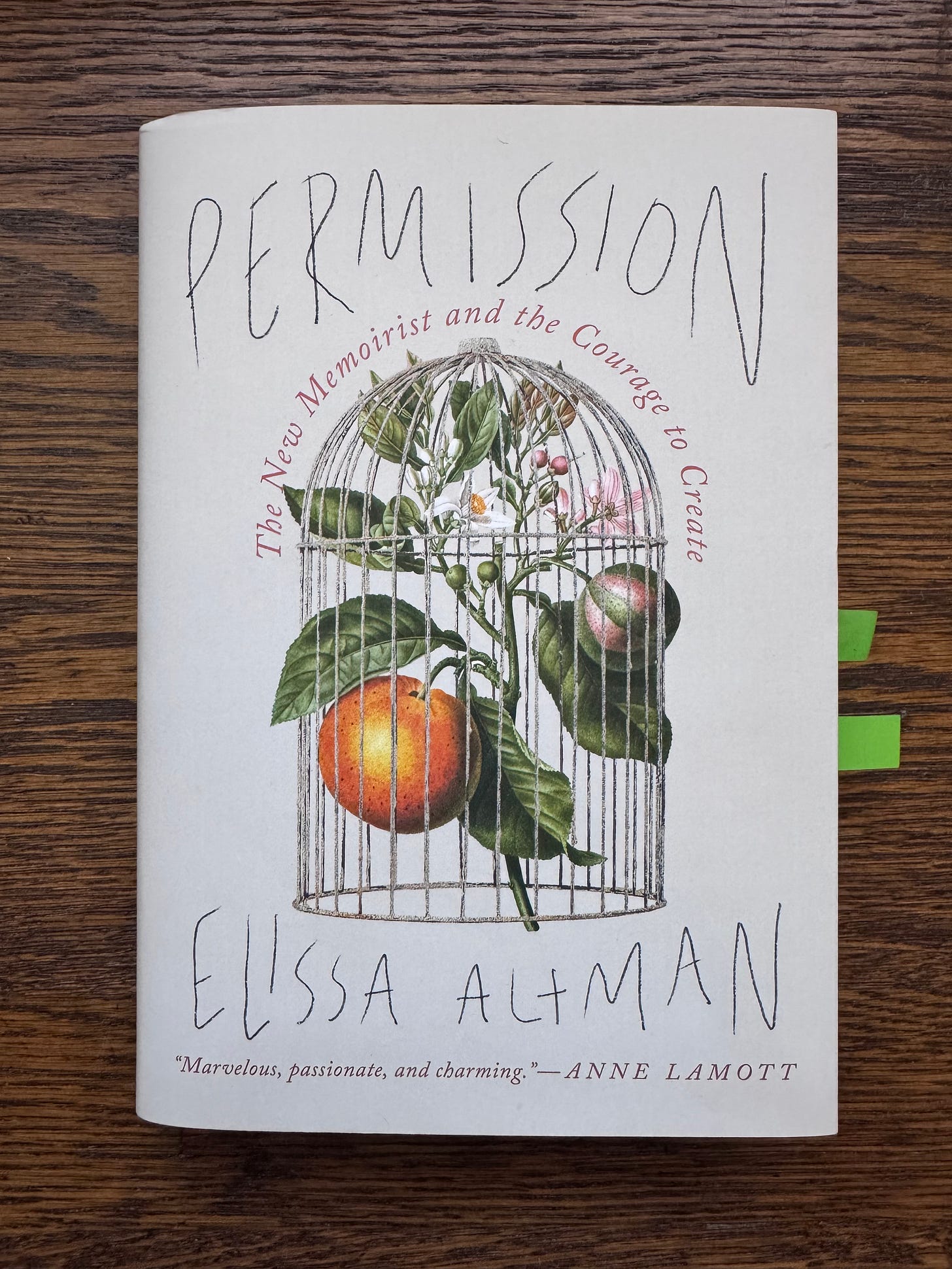

For years, I kept a towering stack by my bedside — all books about creativity and intergenerational trauma and what it means to try and move forward despite all of the voices both loud and small screaming that art-making in the face of grief is an impossibility because one does not yet have clarity of vision and perspective afforded by the passage of time. In fact: art-making in the face of grief is indeed an impossibility, but also an absolute necessity. Artists write, paint, compose, bake, photograph, or knit their way through paralyzing sorrow, and we have done so since the beginning of time; we are, as Robert Macfarlane says, the art-making species. But I did not know this when I sat down to write Permission; all I knew was that my life had changed profoundly, and my loss had dropped me into quicksand that I could not climb out of without slogging through it to get to the other side. Call it what you will: Odyssean, a Hero’s Journey, a Voyage, a Monomyth.

A sunny spring day. I remember what we were eating (sushi, at Blue Ribbon in New York), what I was wearing (the usual: striped Breton, black blazer, jeans, boots), what my dining companion was wearing (black jeans, a blousy silk beige top). I remember coming up out of the subway at the Time Warner Center, making my way through the lunchtime crowds to the restaurant, and finding my lunch date sitting in a booth, their back to the door. I remember that their phone buzzed constantly during the meal and that they answered it every time. I remember their face when they told me I’d never write again, after which they blithely sipped their diet Coke through a striped straw. I remember going to the restroom to be ill. I remember that I never heard from them again after that, not even when, a week later, both People Magazine and Oprah Magazine featured Motherland, my memoir, which had just come out. After that lunch, writing the proposal for my next book — the one I so very much wanted and needed to write — took me years because I heard their voice careening around the inside of my head assuring me that I was no longer the writer I was, and am, and always will be, as though a hot wire had been snipped neatly in two. This person, who shall go nameless, had attempted to take away the thing at the core of what I hoped would be my next book: they tried to take from me my own permission to create a book about permission to create.

Your writing days are done, they had said. And the funny thing — the thing that I only realize now, in hindsight — is that it was an echo of why I was needing to write Permission in the first place: because I had to investigate the idea of story ownership, who gets to claim it and why, after my own experience of once losing people I loved because I inadvertently told a family secret in my first book. This nameless person, over plates of onigiri and unagi in the shadow of the Time Warner Center, told me: You’ll never write again. Find another line of work. And then their phone buzzed again, and they took another call. I went home and got blisteringly drunk. I stared at the walls of my office for a week. And then I went back to writing the proposal. Because it was the book that I had to write in the way that I needed air to breathe, and I knew it with every fiber of my being. It didn’t matter that I wasn’t young enough or pretty enough or previously successful enough or socially popular enough; I couldn’t not write it. The first professional hurdle — someone in the book business telling me to look for another job because I didn’t fit the uniform; they weren’t giving me permission to write this book — had been cleared.

I first came to the subject of permission in 2016, when an essay I’d written appeared on the blog connected to Krista Tippett’s (lifesaving) radio project, On Being. Susan and I were attending my cousin Sarah’s wedding in Vermont when I received a notification that the piece would be published as is, and that it was coming out soon. My stomach plunged. I realized something that now seems obvious: I was making a first foray into publicly talking about a witheringly traumatic event that had happened to me three years earlier, in 2013, that turned my life upside down and nearly destroyed it. Everything that could have bubbled to the surface did: chronic illness, alcohol abuse, suicidal ideation, clinical depression so bad that I spent entire weeks in bed. And still: my first instinct was to reach out and ask permission to publish the On Being essay from the person who had been responsible for trying to take it away. I was considering asking permission to write about permission from the person who had, three years earlier, sought to punish and silence me for revealing an ancient family secret. I never did ask, but I acknowledged the presence of the impulse to do so, and this was the first step in my healing: the understanding of what psychological control does, and the way it can be wielded to make the victim carry the burden, take the blame, and feel the shame.

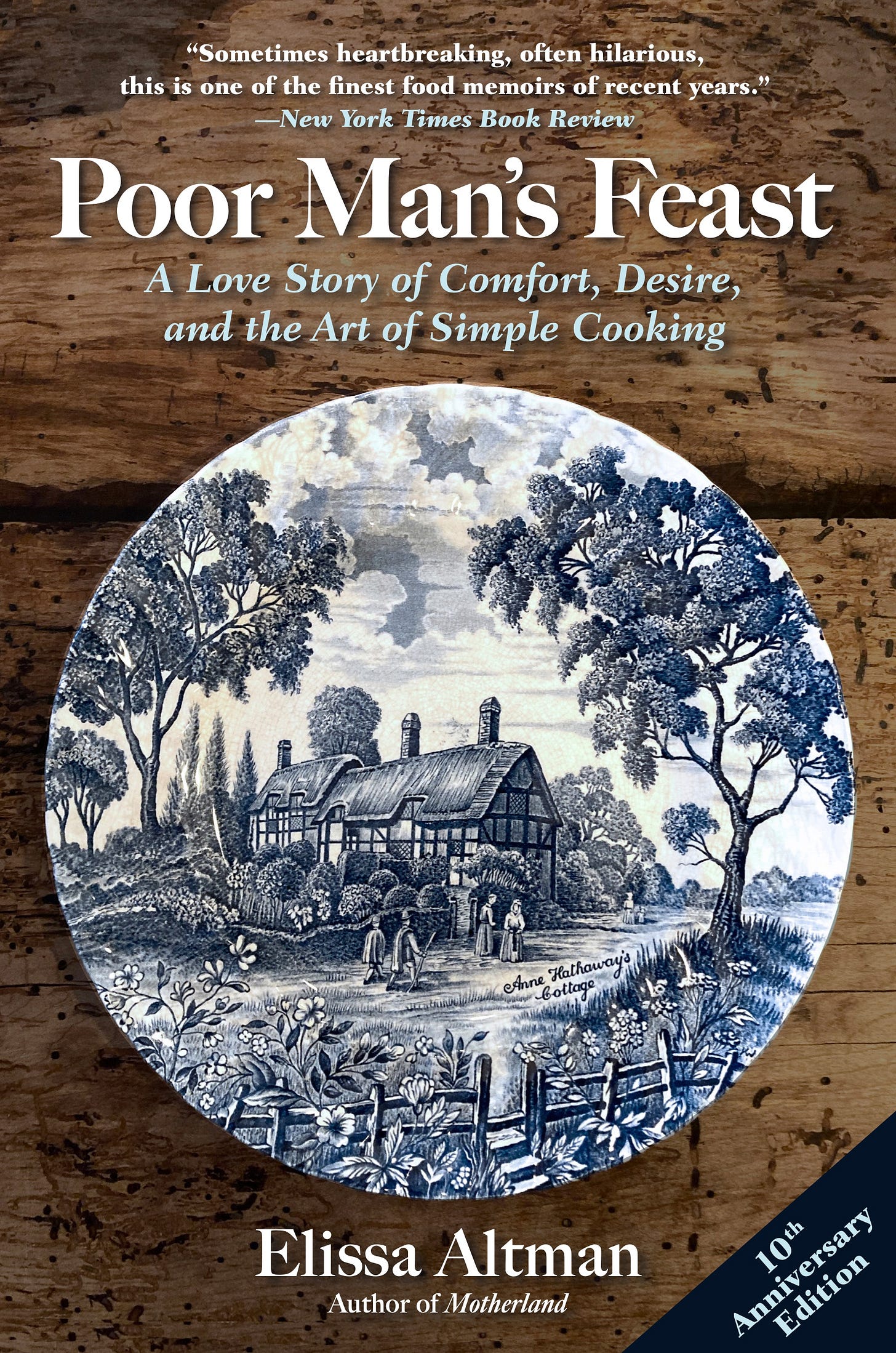

In 2013, I wrote the book upon which this Substack and the narrative blog that preceded it are based. Poor Man’s Feast was a simple story of two women — one rural, one urban — finding love in their thirties and forties, and deciding to spend the rest of their lives together. Coiled around this story was the question of sustenance — gustatory, emotional, physical, spiritual — and why it was a driving force in my life and the life of my father, to whom I was extremely close despite a deeply complicated relationship. His bottomless search for sustenance resulted in a chronic yearning for safety and security; he lived his life needing to feed his broken heart, and he passed along this yearning to me. In an eight-line paragraph towards the end of the book, I get to the why this need was so powerful in his life: when my father was a three-year-old boy, his mother left him, his older sister, and his father for three years. This resulted in both a lifelong, insatiable hunger for safety and a stultifying terror of abandonment, which he also passed along to me. He metabolized the story of his mother’s leaving by telling it to me, like a myth, every day of my life from the time I was old enough to understand words. What I didn’t know was that his sister never told her family, and instead created a life devoted to protecting them from the ugliness of life; her world was about beauty and perfection. In my home, however, it was dinnertime conversation, appropriate or not. The book came out, and half the family was blindsided; one relative to whom I had been extremely close led the charge, and I have been estranged from most of them ever since. The family narrative could not be controlled; the intergenerational story of abandonment begat more abandonment.

This was the first step in my healing: the understanding of what psychological control does, and the way it can be wielded to make the victim carry the burden, take the blame, and feel the shame.

Three years later, my essay came out.

Over the next decade, the story of abandonment and secret-keeping invaded my life; it took over mealtime conversation, and crept into every mundane moment of the day. Susan and I talked about it while walking on the beach in Maine; we talked about it in the car; we talked about it in bed. At the suggestion of one of my early writing teachers, Charlie D’Ambrosio, I read Ostracism: The Power of Silence, by Kipling Williams. Janna Malamud Smith’s An Absorbing Errand: How Artists and Craftsmen Make Their Way to Mastery became my bible, especially her words on shame, and how shame is used against individuals to control them during the creative process, and beyond:

You don’t think shame. You feel covered in its viscose grime. The great hand immerses you whenever you are told you are, or believe yourself to be, violating a basic communal code….Shame [is] a group survival reflex in which the individual is an afterthought. Shame’s first goal is to have you conform to group expectations . . . One way art transforms shame is by replacing helplessness with agency.

I began to ask questions both creative and ethical: in the telling of a story, when is a secret not a secret? Who owns the permission — the right — to tell a story that directly affects them, if it also touches the lives of other people? Similarly, who owns the permission to hide a story and then demands that others hide it as well? If a creative doesn’t know that a particular family story has been hidden for most of a century, what responsibility do they bear in keeping the secret or telling it, even inadvertently, and even though most parties involved are long dead? What is at stake? What are the risks? How can one determine their intent and motivation in writing something that may overturn the applecart but also set it ablaze?

So I wrote the proposal for Permission, which was meant to be a craft book; I had been teaching for most of a decade by that point, and permission, I learned, was the elephant in the room for writers at every level, from National Book Award-winners to those who had only ever written a paragraph before succumbing to shame-based creative paralysis and terror. The book sold to a wonderful small literary publisher, Godine. After months of writing in circles, I realized that I could not write the book without also providing context; I had to tell the story of what happened to me when Poor Man’s Feast came out in 2013, how I had had my heart and my life broken, and how I came to realize that the foundation I thought was beneath my feet all of my life in fact wasn’t. It was based on my playing a role that I hadn’t even known I had been given, and when I stepped out of line, that foundation was pulled out from under me. Because ancient shames have a half-life, like plutonium; they cling to us silently and invisibly, and they don’t leave until we face them.

I was at a writer’s residency in Corsicana, Texas when I realized that Permission was not going to be the craft book I’d been contracted to write; it was going to be one part craft, and one part memoir, because it had to be. I called my editor, the brilliant Joshua Bodwell, who said the words that I’d never heard spoken by any other editor: Let the book be what it needs to be. I wrote my way through it, weaving together questions of art-making and ethics, secret-keeping and intergenerational trauma, and what it means when the Truth enlightens and brings a writer to a place of transcendence, but also destroys everything in its wake. When I got to the end of the manuscript, I was not the same person I’d been a decade earlier: I was a different kind of teacher, a different kind of writer, and possessed of the knowledge that, as Mrs. Ramsay said, A light here requires a shadow there.

It’s taken me this long — twelve years — to step over the threshold that was once inhabited and controlled by the kind of shame that devastates art-makers of every stripe. I needed Permission in 2013, when my family life lay in ruins; I needed to read the story of how someone had the unthinkable happen after their inadvertent revealing of an ancient secret, how they swam through the toxic sludge of biblical ostracism, clinging to the plank of reason, and made it to the other shore gasping for air but alive, and yearning to make order out of chaos.

Since the publication of Permission, I have been in several remarkable conversations regarding story ownership, intergenerational trauma, the roots of Permission, and what it means to heal from devastating loss. Here are some recent favorites:

Daring to Tell with Michelle Redo

Maybe there is something terribly wrong with me, but I know stories much worse than a mother leaving for three years and then coming back. I certainly understand how the children must have felt, but Jesus Christ. Many many worse things have happened to kids. You didn't leave your children. All you did was reveal something you didn't know was kept hidden. Holy shit. As for the side of your fmily that abandoned you? Maybe that is good riddance. I'm so sorry you suffered, were made to suffer for this. I am glad you have put this to bed with your new book.

A good writer tells the stories she needs to tell. A great writer tells those stories because we need them. You are a great writer, Elissa.