Ask yourselves this: if you are over fifty, what are the markers that divide your life into befores and afters? Divorce? Illness? Unemployment? The discovery of infidelity? Sudden destitution? Catastrophic fire?

What are your pivot points? When did everything change?

I mark my middle-aged adult life this way:

Before T***p took office in 2017 but after the 2016 election. Before I went out on book tour for my second book. Before I came home from the tour and dropped my bags. Before my mother called me that night to say the two words that every one of us who still has an older parent will, at some point, hear: I fell. And before everything — literally everything — changed: time, energy, patience, money.

It is not unusual for eldercare to become the very moment when one’s adult life jumps the guardrails.

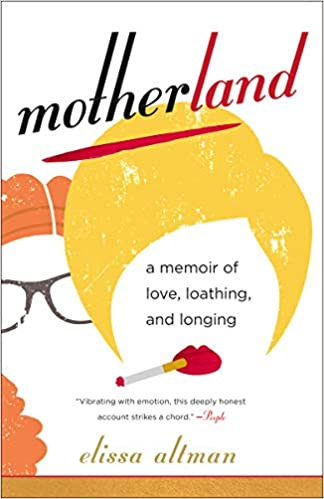

And after? After the election. After my second book came out. After I got home from book tour. And after I suddenly became the caregiver for a parent from whom I was emotionally and spiritually if not physically estranged for the majority of my adulthood. This story — the caregiving-for-the-estranged-mother story — was the foundation of my third book, Motherland which, I gather, made a lot of people (mostly women) very uncomfortable because it asked the question: how do I go about caring for someone who is at the source of my trauma and my existential grief?

It is not unusual for eldercare to become the very moment when one’s adult life jumps the guardrails. Everything goes from being reasonably ordered and predictable — plans, income, schedule, one’s own health and the health of one’s spouse (and children grown and not) — to unpredictable in a flash. Most of us have heard of The Sandwich Generation, which is what happens when you have kids still at home who depend upon you for everything, and elderly parents who also depend upon you for everything. This is not hypothetical or conjectural; it is highly likely that you, if you still have kids at home and elderly parents in need, are a member of The Sandwich Generation. If you don’t have kids (at home or at all), you will be primally inclined to devote most of your energy, time, and money to keeping your elder safe, happy, clean, fed, and healthy. If you are married or partnered, and your partner is an absolute angel, as mine is, your relationship will still bear the burden of the stress of eldercare. If you are single, or a woman, you will be expected to do it all, and you will likely try to, sometimes against your own better judgment. Although I’m not single, I have no siblings to share in my mother’s care so I do it all as only children inevitably do, and I’m always on call, except for when my (angel of a) wife helps me. Which is a lot. And I have maternal cousins who spring into action when I need them, and for whom I’m profoundly grateful.

When the situations come, they come quickly: eight months ago, recognizing that my mother was falling and no longer walking safely — she lives alone in Manhattan — I requested an assessment from the city so that she could get a few more personal aide hours. The intermediary believed that she could be assessed via Zoom, and denied the request for more hours because my mother, in her opinion, seemed perfectly fine on Zoom, where they could not see her walk, or try (and fail) to get up from a sitting position. Then my mother fell twice after that. Then I demanded an in-person assessment, and the third-party assessor was so shocked when she saw my mother attempt to walk that she was approved for the hours I’d requested, and a few more.

On average, I spend approximately four hours a day, seven days a week, on my mother’s basic needs — food deliveries, pharmacy refills and deliveries, doctor’s appointments, dental appointments, apartment repairs, phonecalls asking me the same questions that need answering, forgetting how to use her cellphone, reminding her about her cane, fighting with her about her walker — and another hour or two a day, five days a week, dealing with the bureaucratic nightmare that is managed eldercare in New York City: care managers who don’t answer their phones or return emergency calls, managed eldercare organizations who routinely lose paperwork (powers of attorney, healthcare proxies, statements containing financial information), time-sensitive documents that never arrive, managed eldercare organizations who input incorrect information into their systems, often on purpose (the info is never input to benefit the patient, but in a manner that will automatically deny care), care managers who make executive decisions regarding the number of hours their patients can have an aide in their home. My cell phone rings constantly — when I’m walking the dog, or going grocery shopping, or sitting in my own doctor’s office, or in a work meeting. I spend between four and six hours a day managing my mother’s care, and also managing the care managers when they get things wrong, which is always. Again, I have no children, but if I did — and many if not most eldercare givers do — add to the eldercare numbers the hours spent focusing on childcare. And then tell me why women in their forties, fifties, and sixties often look so exhausted. (I just met an eldercare giver who was in her mid-seventies and caring for her hundred-year-old mother, so we can add seventies to those ages, above.)

Because my mother is not eligible for assisted living, these are the cards we have been dealt. And while assisted living is still no guarantee of safety— my oldest friend’s mother fell in her assisted living apartment in Maine — living in one might have helped my mother when she lost consciousness while on the phone with me last Sunday night and banged her head, hard, on the way down. Respect for elders being what it is, the icing on the cake came when the receptionist for the radiology center where she was having a CT scan yesterday insisted that my mother, who can barely walk lest she fall, stand up and “walk” over to her desk so that she could give my mother an admittance bracelet emblazoned with the words FALL RISK. (A note to this fine individual if she happens to be reading this: the next time an elderly fall-risk patient shows up in your office, YOU get up and walk over to her, and affix the FALL RISK bracelet.)

Over the last ten years, the question of self-care has come up again and again, because those words — self-care — live in the viscera of our culture. What are you doing to take care of yourself?

When my mother had the catastrophic accident that changed her life, she was eighty years old; I was fifty-two. It was nearly a decade ago. During the days after her fall in which she exploded her ankle and required two surgeries, seventy-five screws, and two plates, we learned that my mother kept her important papers in a large plastic furrier shopping bag in her bedroom, including bank statements from the Reagan administration. We learned that she had acquired the very worst possible insurance — Medicare Advantage with a $0 premium — and that they covered nothing, not even for an eighty-year-old woman; they even attempted to not cover her surgical anesthesia because, they said, Everyone knows that old people don’t feel pain. Her hospital copay was $181,000, and her rehab threw her out before she could put weight on her feet (she broke her foot as well as her ankle). By sheer luck, a wonderful private personal aide who had worked for an old friend’s ailing father was available; she moved in with my mother for ten months, at a breathtaking cost that totaled well into the six figures and was not covered by Medicare. I am in the vast, vast minority of people who, faced with eldercare, had to somehow find a way to afford this, nearly bankrupting myself in the process. According to the Center for Elders and the Courts, the population of Americans over the age of sixty-five will have doubled by 2030, meaning that number combined with the cost of healthcare will result in millions of underinsured, uncovered seniors facing certain destitution.

Over the last ten years, the question of my own self-care has come up again and again, because those words — self-care — live in the viscera of our culture. What are you doing to take care of yourself? When can you rest? Are you eating well? Are you moving your body? Are you getting enough sleep? Can you take a break?

Here’s the truth: breaks, for many of us, come in very tiny bites. When my mother calls fourteen times in one day because she’s lonely or bored or isolated, I cannot say to her I’m sorry, I’m taking a break from you. (Although if she’s being abusive, I do.) Nor can I ignore her calls because, now that she is a high fall risk, any number of those calls might be to tell me that she’s fallen. What am I doing to take care of myself? Trying to get as much sleep as I can. I used to shut my phone off — both cell and landline (I keep the landline just for her use) — because my mother’s circadian rhythm is so screwed up that she confuses dawn and dusk, and has done since I was five, so she will call me all hours of the night just to chat; I don’t shut my phone off anymore because it is too great a risk. Am I eating well? Sometimes. Susan will often take over dinner responsibilities, and make us meals that are light, vegetable-forward, healthy, and delicious. Am I moving my body? Yes. From my bed to my office to my bed to my office. My body needs more movement, and my brain, which has begun to resemble a wind-up cymbal-playing monkey, has to be quieted.

I write this neither for pity nor advice, because the American healthcare system combined with the way we treat the elderly is very, very broken. But I do want those of you who are facing eldercare or who are in the throes of it to understand: you are not alone. Not by a long shot.

My body needs more movement, and my brain, which has begun to resemble a wind-up cymbal-playing monkey, has to be quieted.

This morning, the word CAIM arrived in one of my social media feeds. The definition: a sacred space where one can feel safe, grounded, and shielded from external harm or negativity. I imagine myself in this place, and I have a number of them in my life: a hiking trail on the upper ledge of Mt Tamalpais in Marin, the meditation room at the Cliffs of Moher in County Clare, the Backs in Cambridge behind Kings College Chapel, the Quaker Meeting I’ve recently attended near my home. If there is anything that will keep me safe at times like this, it is the sacred, and that which grounds me.

Recently, my friend Katherine May wrote about anxiety and groundedness. She said

I am often asked how I stay hopeful as the world steadily darkens. The answer is that I don’t think about hope at all. Hope is none of my concern. It is not what’s needed for us to survive, and we should not wait for hope in order to do what is necessary. I’ll take groundedness over hope any day, a sense of connection to the land beneath my feet, to the life that grows from it, to the people who walk it.

Groundedness is the opposite of anxiety, an anchor to our floating.

I’m grateful for her words, for the way they anchor me, no matter what my eldercare continues to look like in the coming months.

It is one thing to care for a parent who lovingly raised you as a child. It is another situation to spend years of your life caring for a parent who did not. Can we talk about the reason that the daughter is so often the one on whom this falls? Can we also talk about the resentment that is sometimes inevitable when you are caring for a parent for what feels like the last remaining good years of your own life? And the expectation from society that you will do so, without complaint— even in the face, sometimes, of abuse. How dare you be selfish! How dare you have needs! How dare you stand up for yourself! Your mother needs you! I did not talk to my mother for three months in her 93rd year, and she also died six months after that. It was right and needed at the time. Such a complicated scenario in so many ways. Sending you compassion, grace, understanding, and kindness. I see you.

There is an old African saying:

You cannot walk where there is no ground.

Such a simple truth.