I used to believe that a failed garden was the first sign of trouble.

Domestic concerns; boredom; disinterest; bodies that have changed; a long relationship on the fritz. In the early autumn of recent years, I couldn’t even set foot beyond the gates without worry; the raspberry vines from beyond the far fence that separates our property from our neighbor’s cascaded into our perennial bed, choking everything in their way: chocolate astilbe, lovage, peony stalks. Summer squash — Striato di Italia and Zucchini Romanesco — grew to the size of watermelons because we’d either forgotten to eat them, or forgot them entirely. Every year, our chard overruns its box; our lemon balm takes over everything it can. This year, the chard was eaten by rabbits days after the starts were planted. The two farthest boxes are caving in on themselves, filled with weeds, the Douglas fir boards now splitting and rotting. They’ve lasted twelve years — we built them ourselves back when I was editorial director at Rodale Books: a good run.

When we left for Maine two Septembers ago, the beans we’ve grown annually for almost twenty years were healthy and lush and vigorously climbing their tuteur. We’ve always let them dry on the vine; we harvest and shell them, and save them for winter soups and stews. Last year, Susan wrapped the bottom half of the tuteur in row coverings just to keep the deer from eating the leaves and vines while we were away on our annual trip. We forgot to do it this year, and when we got home, all we had left was the vaguest evidence of life: vines stripped of their color, a few stray leaves browning in spots, and enough beans to make two pots of soup. Cropping up everywhere: poison ivy and poison oak so robust that my neighbor had to take a course of prednisone thanks to the patch that quietly crawled beneath the pavement between our property and appeared in her yard.

We first built our garden a decade ago, after a violent storm destroyed a family of five trees adjacent to our house, leaving them so weak that one hurricane — one good gust of wind — could send them crashing into our roof. We hired an arborist to come out and look, and tell us what we needed to do.

I only realize this now: that grief seeps into one’s pores and it stays there for good; it sets up shop and puts up wallpaper and it doesn’t leave, and you come to understand that it is simply a part of your DNA.

Nothing to be saved, he said, and the next day, his crew returned with him and took down all five trees and I cried over a cup of tea.

When they were done, Susan and I had a massive, flat, mostly sun-splashed space alongside the house where one had never before existed. One night, we took some graph paper and drew up plans for a huge garden roughly thirty feet long by fifteen feet wide, containing six eight by three-foot vegetable boxes, two Adirondack chairs, and a perennial bed on the inside of the far picket fence, which went around the inside perimeter of the space. We hired a friend’s contractor husband to build the fence and put down pea gravel mulch (a bad idea, the pea gravel mulch), we built the boxes ourselves and filled them with garden soil and compost. A month or so later, we began to plant.

That was the summer of 2012 — six months before my first book came out and rendered me tribeless, and four months before the shooting in my town that would change everything I thought I knew about safety and children and the value of life, even as some people claimed it never happened. I only realize this now, looking back from the vantage point of having survived abandonment at the age of forty-nine by people I had always been told loved me, and having lived through the thing that happens when strangers taunt the grief-stricken with cries of fakery, even as they lowered their children’s caskets into the ground, and our local St Rose of Lima held funerals every single day for weeks. I only realize this now: that grief seeps into one’s pores and it stays there for good; it sets up shop and puts up wallpaper and it doesn’t leave, and you come to understand that it is now a part of your DNA, your genetic makeup, like the color of your eyes or the texture of your hair. It has altered who you are at the most fundamental level.

But gardening is a contract with hope.

So we built, and we planted: over the course of a decade, we grew carrots and chard, beans that Marcella Hazan identified for us as baby borlottis, garlic, pinto potatoes, Robeson tomatoes, Lacinato kale, cabbage, Little Gem lettuces, Buttercrunch, Rouge d’Hiver, French breakfast radishes, Progress #9 peas, Yellow beans, Eight Ball summer squash, Red Kuri, Musquee de Provence pumpkin. We’re completely organic so we have fought blight; we have fought pests. One day early on, I looked out at the beans and saw something shaped like a brown furry bowling ball with legs, eating the leaves: I turned away for a minute or two to clean my glasses, looked back out, and there was nothing left of the bush. I might be imagining it, but I feel like it flipped me the bird: Fuck you, it said. You humans think you can control everything.

But gardening is a contract with hope, as I wrote in Motherland. And so with every year, we planted more beans, more radishes, more lettuce, more squash; sometimes it was a terrible year, and sometimes it wasn’t. The family that had stepped away from me grew more and more distant, like figures shrinking in a rear view mirror; most of the first responders in our town left. Covid killed colleagues and the parents of friends; I had a Covid stroke. My aunt died at 102. Susan developed very serious skin cancer. I became the last living Altman in our line. I lost beloved friends to misunderstanding and bitterness. I got older; Susan got older. Our garden boxes began to disintegrate. Poison ivy took over and thrived.

All we have left are tomatoes, which have been pulled back from the brink of fungal doom.

This year has been a very different sort of New England summer: it’s been soggy and damp, very hot, and impossible to be outside for long periods of time. The vegetable garden this year was supposed to be entirely my responsibility, and the native perennials in front of the house, Susan’s. Early on, I decided that we really only needed four working boxes as opposed to six, and I let two of them go; they bore masses of wild foxglove, and the lemon balm that crept out of the boxes and choked the chamomile and the carpet thyme. Our hollyhocks never came back, and the chocolate astilbe in the corner of the perennial bed was again taken over by raspberries. For the first time in twenty years, we neglected to plant the baby borlottis or the yellow beans. I planted three different kinds of lettuce, and a large family of bunnies immediately ate them all. Our zucchini succumbed to squash vine borer and a vigorous eight-foot climbing plant was dead within a few hours. Our cucumbers failed. All we have left now, at the end of July, are tomatoes, which have been pulled back from the brink of fungal doom with Susan’s regular spraying (she, who was only supposed to deal with the perennials took care of the vegetables too when I found myself so depressed that I couldn’t drag myself in through the garden gates).

Not only did the warm, wet weather play host to all manner of crawling creatures that did not respond to (organic) spraying; it appeared the soil in which everything was attempting to grow was dead. I had amended it with rich compost and let it rest before planting anything, but it was not enough. The soil needs to be dug out, mixed again with more compost, and planted over with cover crop. And with the first turn of my shovel next March, I will hope to see hundreds of worms as evidence of life. But this year, there were none.

We have finally come to grips with the fact that a dying garden is no longer a reflection on us and our various failures, but rather, the passage of time and the change in environment. We want and need a smaller growing space. We are now only interested in planting what we know will grow and flourish. I just need a small plot, big enough to grow food for us, and to share with our neighbors. I will not reap to the edges of my field, nor will I glean what falls. I will put on elbow-length gloves and cut off the bottoms of black plastic contractor bags and slip my arms into them, and pull out the poison ivy wherever I find it: by its roots and its leaves and the vines that strangle my trees and my flowers. It will return year after year, and I will pull it out, year after year, wherever it shows up.

And when the autumn arrives and the garden looks like hell, I’ll cover it up until the next season, and try again.

Devonshire Honey Cake

(adapted from BBC Good Food)

Susan, who is of mostly British lineage, found this recipe at BBC Good Food while we were up in Maine last year. I had never heard of a British honey cake; my family’s older recipes usually have in the neighborhood of twenty ingredients, some of them unfathomable. This cake is now our standard; it manages to be flavorful but not terribly sweet (my late grandmother’s could make your teeth fling themselves out of your head like Chiclets). My grandmother ate her honey cake with a cup of strong tea, as do I.

Note: We always measure baking ingredients using a scale, so there was no need to translate grams to ounces. I did, however, change the gas mark and pan size directions.

Makes 12 slices

250g clear honey, plus about 2 tbsp extra to glaze

225g unsalted butter

100g dark muscovado sugar

3 large eggs, beaten

300g self-raising flour

Preheat the oven to 325 degrees F. Line an 8 inch springform cake pan with parchment, and butter it. Cut the butter into pieces and drop into a medium pan with the honey and sugar. Melt slowly over a low heat. When the mixture looks quite liquid, increase the heat under the pan and boil for about one minute. Leave to cool for 15-20 minutes, to prevent the eggs cooking when they are mixed in.

Beat the eggs into the melted honey mixture using a wooden spoon. Sift the flour into a large bowl and pour in the egg and honey mixture, beating until you have a smooth, quite runny batter.

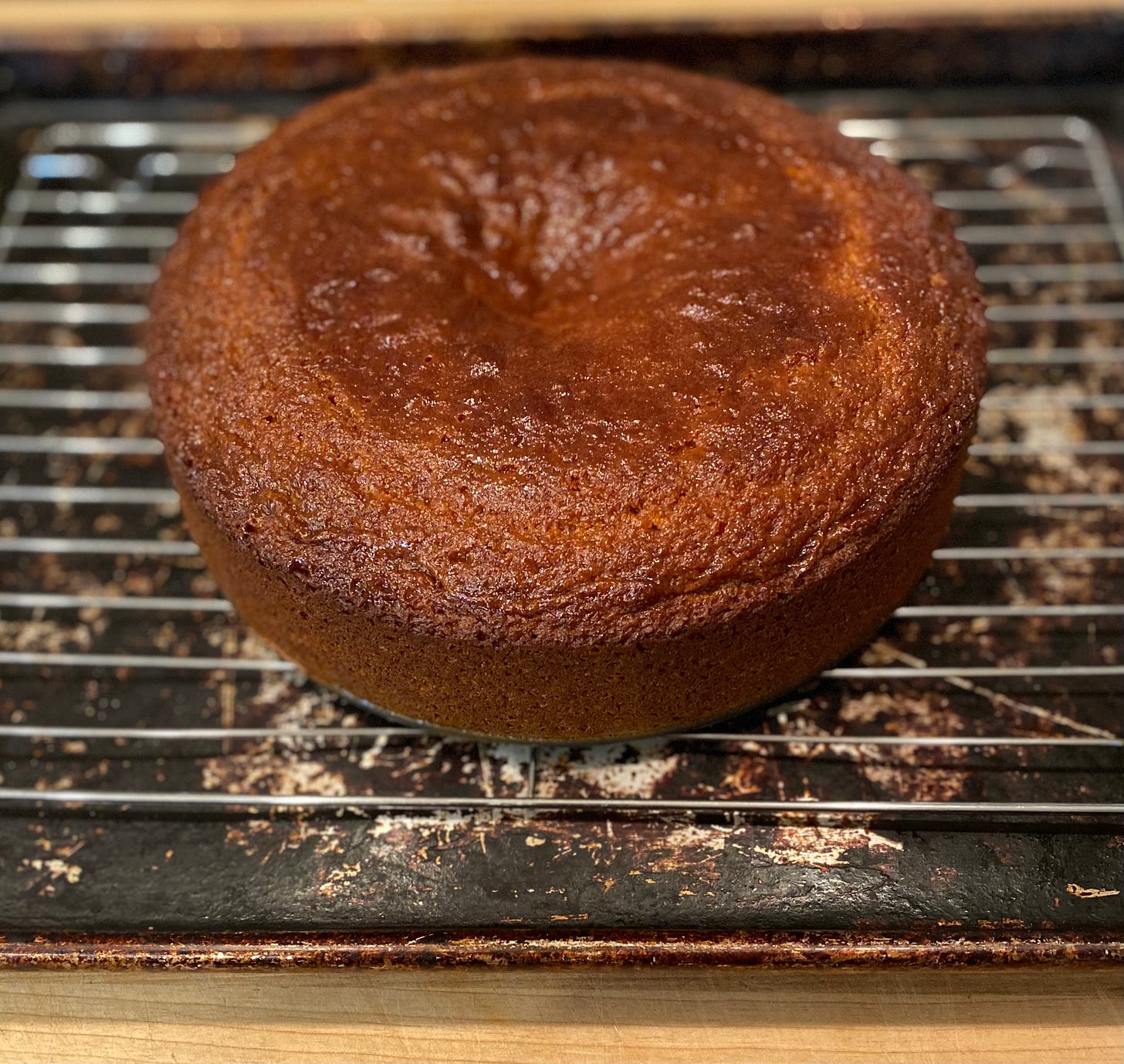

Pour the mixture into the tin and bake for 50 minutes-1 hour until the cake is well-risen, golden brown and springs back when pressed. A skewer pushed into the centre of the cake should come out clean.

Turn the cake out on a wire rack. Warm 2 tbsp honey in a small pan and brush over the top of the cake to give a sticky glaze, then leave to cool. Keeps for 4-5 days wrapped, in an airtight tin.

An earlier version of this essay was published in 2023.

Elissa, I just found and subscribed to your substack last week. Seeing this post in my inbox today, I momentarily forgot who, what, when, and how it came about, and then I remembered and read on. I am so moved by this piece, thank you. On another side of hope, I moved this year and found myself without any green space to grow and garden, and in a basement unit, without meaningful amounts of sunlight, for myself or my plants. I was feeling so lost and all my beautiful cherished houseplants started to die, I found myself stepping outside onto my patio only to be eye-level with nothing but grey gravel and shoes. In early spring with a dream to see green things, I bought planter boxes and nasturtium, pansies, lemon thyme, basil, and two brightly coloured potted flowers. I tended to them fervently inside, with the 5 plant-saving grow lights I purchased when my plants started to turn. As I look outside now, I see six little boxes of lush green foliage, herbs, pollinator friendly flowers, and market carrots growing alongside marigolds. When there is the need and the will to see life grow and bloom, it will always find a way. Thank you for your words.

I feel such relief reading this Elissa! Our veggie gardens in the PNW have also dwindled this year, a combination of an unseasonably chilly spring, ravenous birds and overly zealous composting that stunted and yellowed all my starts. And now I’m down with Covid 12 days and counting and anything that does look harvestable is tossed to the hens because canned chicken soup is about all my energy can muster. Allowing the cycles to exist instead of asserting our illusory control is such a good way to be. I so appreciate the reminder and can breathe a bit more deeply after reading. 🙏