We know this: the act of cooking is physically, emotionally, and spiritually sustaining.

We know that food is a metaphor for peace, history, family, comfort, stability, instability, nurturing. At its most fundamental, it’s fuel. We — whether we walk on two legs or four or more— eat to live. For humans, the entire process —- the shopping or harvesting, chopping, boiling, peeling, poaching —- can be meditational and soothing, or it can be utterly discombobulating. It can tell a story of place and time and family; it can tell a story of war. It can be focusing and calming, or it can be dangerous. Let your attention wander while you have a sharp knife in your hand, and you will have a sharp knife in your hand. Once, when I was catering my first New York City luncheon for a well-known art collector and patron, I finished slicing a side of smoked salmon and drew the special, foot-long knife across the towel I was holding, missed, and sliced my hand to the bone; I wasn’t paying attention. For me, though, the danger part is usually irrelevant, because when I am undone —- distracted, furious, anxious, shaky, unsure, fearful, paralyzed with worry —- I have zero interest in food. Not cooking it; not eating it; not feeding it to anyone else.

When the bottom is pulled out from under me, I can’t, and don’t, and won’t sustain myself.

The fact that it was recently Christmas allowed me to compartmentalize world events for a little while, and focus on the Neal’s Yard Stilton in my cheese-keeper, and the spot prawns and ham in my fridge. But since then, I have completely lost my appetite (beyond the norovirus I managed to come down with over the weekend). This is a thing with me: when I am upset, I don’t eat. When the bottom is pulled out from under me, I can’t, and don’t, and won’t sustain myself. When I’m so unmoored that I feel like I’m living on one of those amusement park rides that spins forward and forward and then backward and then tilts as centrifugal force plasters everyone to its insides while the floor literally drops out until the riders are physically ill: I don’t want to look at food. When my father dropped me off at college for the start of my freshman year at Boston University, I did the opposite of gain the Freshman 15: I lost so much weight during my first month at school that my jeans hung off me like a burlap sack. I hadn’t even noticed that I wasn’t eating until my dormitory neighbor and closest friend, concerned that I might be unwell when I stopped having the energy to get out of bed in the morning, dragged me to meals with her, three times a day.

Over the years, and because of the toe-dipping I have done into various twelve-step programs of different stripes and methods, I have become well-acquainted with the acronym HALT. My hands shake when I’m HUNGRY or ANGRY or LONELY or TIRED. I crawl out of my skin. Everything is too loud and too bright, and I feel as though I am unsafe. I try and identify HALT long before it happens, and although H is for HUNGRY, HALT hunger doesn’t actually hit me as hunger, per se, but as a sort of dizzying lightheadedness associated with anxiety, fear, fury, or the kind of quiet panic that is the precursor to fight/flight/freeze. It’s not a stomach-rumbling hunger, but an existential one, and if you give it a little push —- the merest nudge —- it lists over into full-bore self-loathing and terror, and this is when I stop cooking and eating. Because, if I am as awful as I think I am, as everyone else tells me I am, as undeserving of the rights that are due me as a taxpaying citizen (of a modern democracy that my father and uncle fought against the Nazis for) are under siege, why bother to care for myself. I mean, really. What’s the point?

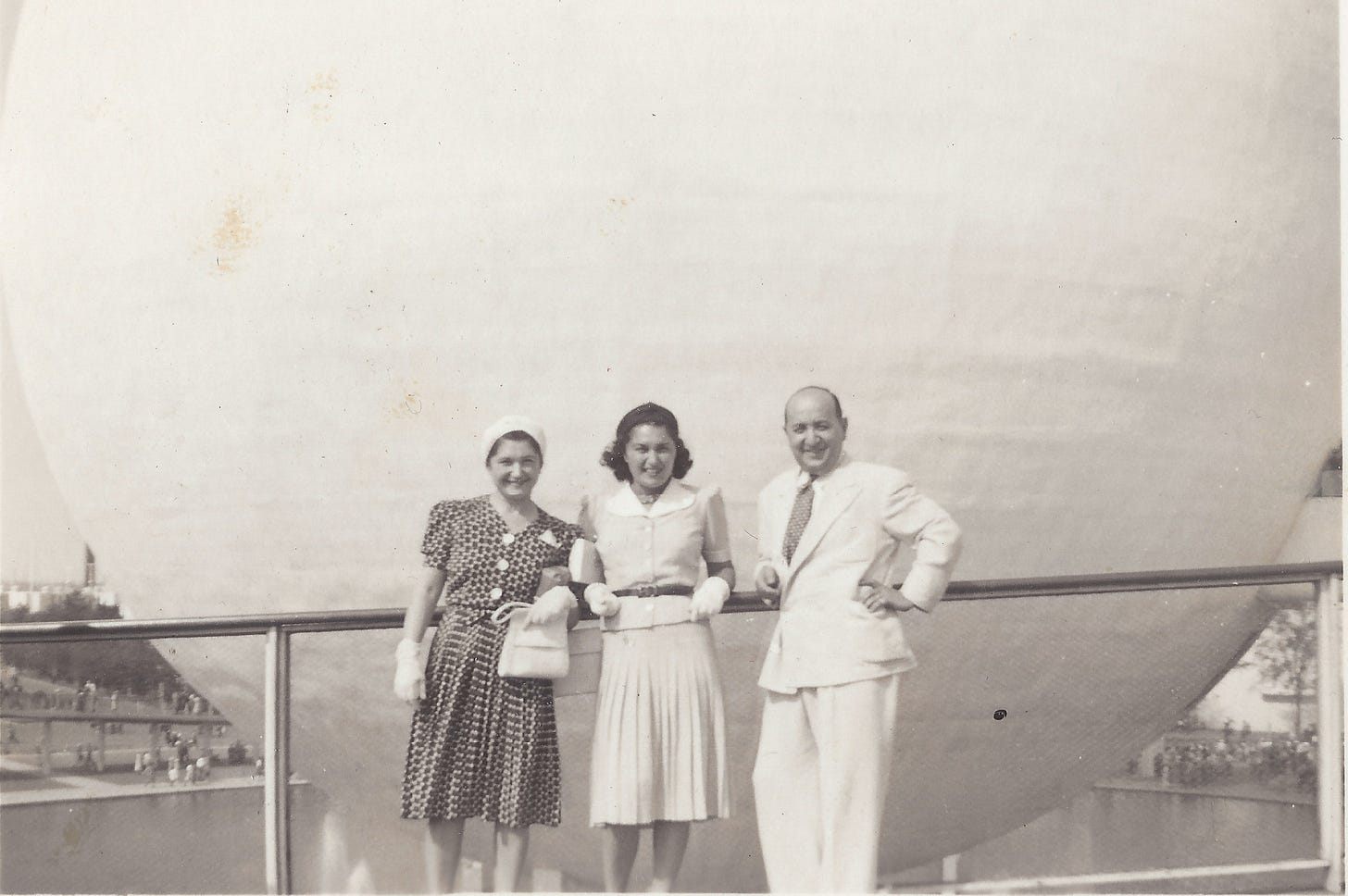

My paternal grandmother —- an elfin woman/badass Brooklyn cardshark to whom I was not particularly close after my mother helpfully turned her into a pariah (the story is the foundation of my new book, Permission, and is also in Poor Man’s Feast-the-book, and Motherland) — used to call me when I wasn’t feeling well and say Can you take sustenance? It always struck me as an odd thing to ask —- it had such an antiquated feel to it. But it was spot on.

Can you take sustenance? Can you accept that which will feed your body and spirit? If you can, what will it be?

So all these years later, when the bottom drops out and I’m shaking with rage, or fear, or withering sadness, or all of the above, I ask myself this question while in the throes of HALT and the self-loathing it engenders in me. Can I take sustenance? And if I can, what will it be?

As I write this, Susan and I have become new humans to a rescued senior-ish Golden Retriever who, I am convinced, has some training as a therapy dog. (We know nothing about him beyond the fact that he came from Puerto Rico, and, judging by his response to a recent thunderstorm, might have lost his humans in the hurricane that decimated the island in 2017.) The other morning, I was lying in bed feeling particularly undone by the news and eldercare-giving and the jitters that come with having a new book about to be published, and this dog — Fergus is his name — who weighs 80 pounds and is essentially a furry golden mountain, climbed onto the bed and stretched out across me, width-wise, pinning my body, my hands, and my legs. It was like being buried beneath a giant wagging weighted blanket. When I tried to move, he sighed, put his head down, and went to sleep. On top of me. I gave up trying to move and clung to him like a life preserver, and he apparently made the executive decision that I was not going anywhere until he deemed it safe. So we stayed that way for a while. This too is a form of sustenance.

But one must eat, and assuming I have enough energy to cook at all, I have learned the hard way what I can tolerate: nothing fancy, nothing complicated, nothing acidic, nothing sweet. Essentially, I am describing what Elizabeth David would have called nursery food, and that’s fine. Diets can wait; clean eating is a terrific idea, but not necessarily in moments like this. When I can’t get out of bed, I do not crave a smoothie with a shot of wheatgrass (if you do, God bless).

Here is my list of what to cook on my Broken-Heart Diet, in no particular order, and based on the contents of my pantry:

1- A baked potato + butter + black pepper + salt. Preheat the oven to 450 degrees F. Poke a large russet potato a few times with a fork. Throw it into the oven, on the middle rack. Let it bake for about 45 minutes, until the skin shatters when you give it a squeeze. Slice it in half (but not through) lengthwise and widthwise and press the ends of the potato toward the middle, so it opens up; add the butter and black pepper.

2 - Buttered toast. Don’t get fancy. Cinnamon raisin, which I normally hate, is good here, provided the butter is salted. If you love Marmite the way I do, butter the toast first (with sweet butter; Marmite is salty) and then add a swipe of Marmite. Katherine May and I have had several conversations about this.

3- Pastina + butter + black pepper + Parmigiana. The first time my northern Italian godmother made this for me, I actually cried. You know when a little kid is so sleepy that they start to cry from relief when you put them down for a nap? That’s what happened to me, only with pastina. Cook the pastina, drain it, toss it with butter, and add the black pepper and Parmigiana. Take to your bed.

4- An egg fried in toasted sesame oil + rice wine vinegar + cooked rice noodles + tamari + scallions. Get out a small stick-proof pan and put it over medium heat. Glaze it with a dribble of toasted sesame oil. Carefully break in the egg, and let it cook for however long you’d like (I like medium soft). When the edges begin to brown, drizzle in the smallest amount of rice wine vinegar. Slide the egg out onto a single serving of cooked rice noodles, add the tamari and the scallions (and if you’re feeling energetic, some toasted sesame seeds).

5- White rice + butter + American cheese + black pepper: Cook a cup of white rice however you want to. My method: put it in a sieve, run cold water through it until the water is clear, put it in a small saucepan, and add enough water to come up to the first knuckle of your index finger. (Naomi Duguid taught me this trick.) Bring it to a boil, reduce it down to a low simmer, cover it, and let it cook for 15-20 minutes, or whatever the instructions tell you to do. Take it off the heat, leave the cover on, and let it stand another 8 minutes. Remove the lid, add a tablespoon of unsalted butter and two (sometimes three) slices of American cheese (preferably white; don’t judge me), cover the pan for another 5 minutes until the cheese is mostly melted, blend it in with a fork, add black pepper. If you want to get fancy, add chopped parsley. The end.

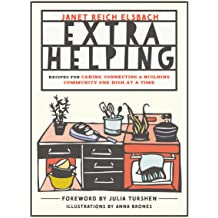

There is a wonderful book devoted to cooking for those who are undone (including oneself), and it ranks as one of my all-time favorites to read, let alone cook from. Janet Reich Elsbach’s Extra Helping is a lifesaver even after normalcy begins to reveal itself (and even after). I’m not sure when that will be.

In the meantime, ask yourself the question: Can you take sustenance? What will it be?

As a grieving widow, feeding myself has been a challenge. I love the idea of nursery food, since I have felt like a baby growing up all over again.

On Nov. 6, I was out at my community garden plot and met up with a fellow gardener when we were fussing with wheelbarrows. He asked me how I was doing. "Upright and taking sustenance," I replied. He stopped in his tracks, spun around, and opened his broken heart.

Take good care, Elissa.