The Permission Workbook: An Introduction

Making Order Out of Chaos

Welcome!

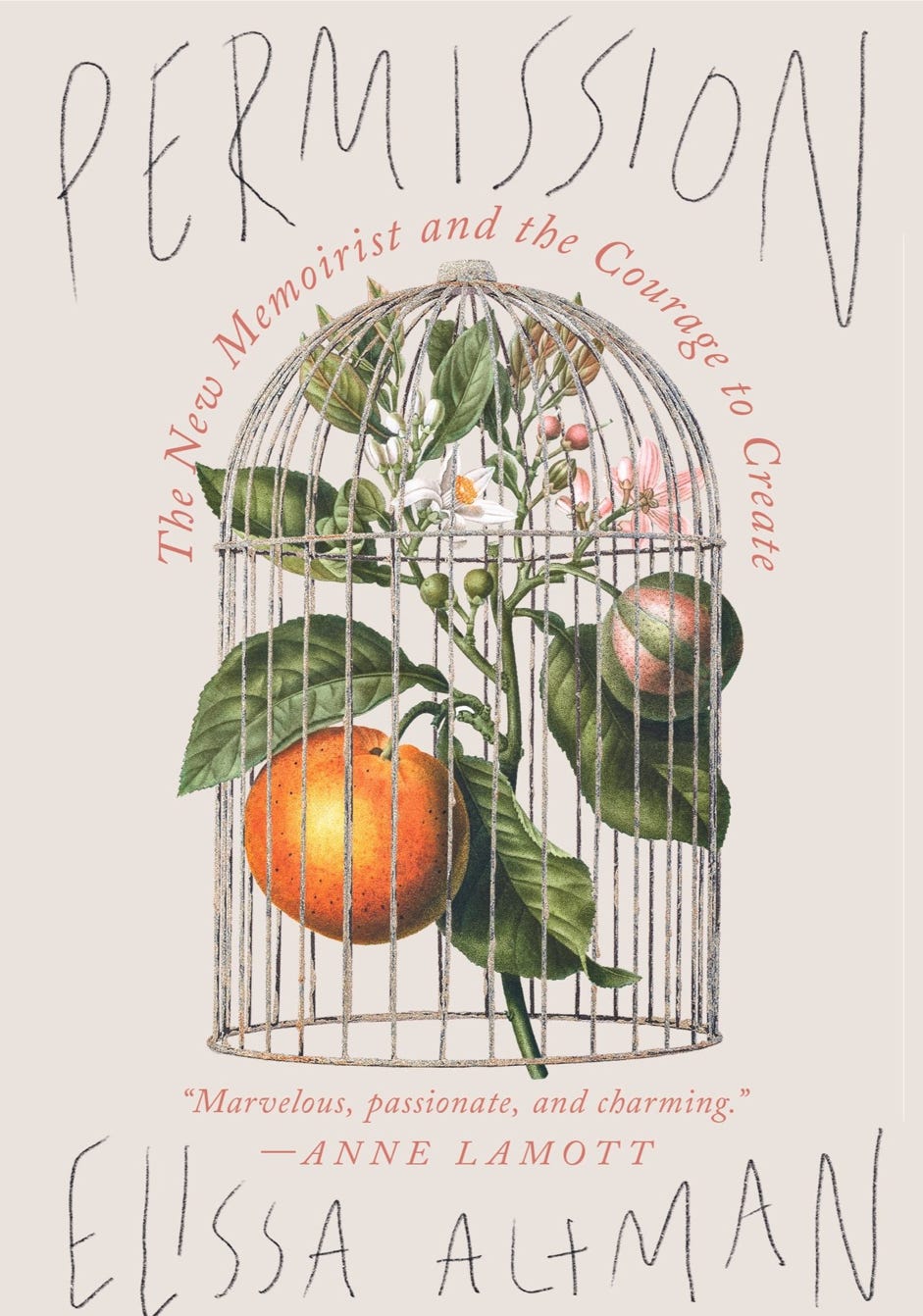

When I began writing the first draft of Permission back in 2023, it was meant to be a different kind of book than what is now in bookstores. As always, and as a teacher, I was interested in the intersection of personal stories and the manner in which we tell those stories. In other words, the book was meant to be heavily focused on craft.

But there were, inevitably, complications. We live in a world of exceptionalism compounded by instant social media visibility, which leads to issues of comparison, competition, and elbowing-for-room: many of my students would tell me that they simply didn’t think that their story — the one they desperately wanted to tell, that they had to tell — was big enough in the broad scheme of things to even warrant writing about, compared to the stories of others. They put it through what I call the So What test.1 And because of the world in which we presently find ourselves creating, writers and artists of every stripe and level of skill are faced with a conundrum that is algorithmic in principle: given our dizzying states of distraction and storytelling overload — every single thing that captures your attention from the news cycle to the sports scores is in some way a story — competition for the attention of readers is, at minimum, fierce. The result? New and seasoned writers alike are given to metaphorical creative shouting (look at me! look at me!), and the belief that their story must be truly extraordinary — earth-shattering, mind-boggling, devastating, over-the-top, unfathomable — to stand out in a roiling sea of art-makers and storytellers vying for the same space and air time.

First: when people make the not-extraordinary-enough statement to me, I always ask How much of the book do you have written? Most of the time, it’s very little, and sometimes, they haven’t even started writing. Which means that they are worrying about something that may not yet exist. This self-censorship does not do good things for the creative process, as you’d probably guess.

The bigger issue, though, is the concept of extraordinary. Isn’t the fact of being a human living on this planet enough? Doesn’t the human condition — that mash-up of day-to-day mundanity — result in the most stunning stories that stay with us forever? Think about it: Mrs. Dalloway decides to buy the flowers herself. Rachel Cusk’s Arlington Park takes place over one day, as does Ian McEwan’s Saturday. (Obviously, yes, these are masters of the form.) But scroll back: Dante suffered a severe midlife crisis and found himself crawling through nine circles of hell to get to the other side. Odysseus was away fighting a ten-year war, his wife Penelope believed him dead, and it took him another ten years to get back home to her; each trial that he faced on his journey (lust, monsters, etc) was like a visit to every rest stop along the New Jersey Turnpike on the way from New York to Philadelphia. His greatest challenge was his ego — hubris — in the same way it was my father’s when he refused to ask for directions. Elizabeth Bennett and Mr. Darcy couldn’t stand each other; their enmity was, in fact, combustive attraction. A story as old as the hills and as human and recognizable as the back of your hand.

Tales of overcoming tribulation, trauma, illness; of falling in and out of love; of combatting monsters — be it Geoffrey Wolff’s father in The Duke of Deception, AIDs in Mark Doty’s Heaven’s Coast, sexual abusers in Lexi Bean’s Written on the Body, alcohol in Caroline Knapp’s Drinking: A Love Story — these are all deceptively simple tales that are representative of the human condition. It was in the crafting that their magic was revealed. Again, it is not just the story that needs to be exceptional, which can be as mundane as air — it is how it is told.

When I was a year into writing Permission, I realized that what was missing from the first draft was the story that bore it; it needed context, lest it fall into a kind of Reader’s Digest-y Three Steps to Better Writing kind of guide. Everything that I taught and every situation that I laid out for the reader to unravel had to be represented by the story of The Thing That Happened to compel me to write it in the first place. And because we will be together for a while here in The Workbook, I will share that context with you. There is a more detailed version of this story in Permission, but here are the Cliff Notes:

Every family has a core legend, a koan — a defining, foundational, sometimes cryptic narrative around which its generations are coiled. Left unresolved, it will pop relentlessly back to the surface like a rubber bath toy. It is the story that appears when we least expect it, in primary relationships both successful and failed, in parenthood, at work, in recovery meetings, in the patterns that our therapists tell us they see. It is an endless loop—a thin Möbius strip that vibrates like a guitar string — and this is mine: In 1926, when my father was three and my aunt, eight, my grandmother abandoned them along with my grandfather, for several years, ultimately returning around 1930-31. My father processed his lifelong trauma by constantly talking about it in my childhood home, which directly resulted in my having a sometimes unmanageable fear of abandonment that exists to this day, and informs much of my work. Inappropriate or not, I was made to carry the burden of my father’s story, which had been passed on to me like DNA. My aunt, however, processed her trauma by hiding it from her children and husband and never speaking about it as a way to protect them. Because I didn’t grow up in my aunt’s house or with my cousins, who are significantly older than I, I didn’t know that it was a secret, or that one of my cousins, in her sixties at the time of publication, had no idea that Grandma had abandoned our parents as children. A year later, as a result of the book, I had been sliced out of my family for having publicly revealed this great and awful secret that I had no idea was a secret. I have been estranged from them ever since. The cycle continued: Abandonment begat abandonment.

I will spare you the details of how it unfolded (or the sub-stories that I am now excavating, including the knowledge that nobody ever bothered to ask why my grandmother left), beyond the fact that my life post-excision looks very different from how it did before publication. There was profound grief, confusion, devastation, and a ton of therapy — I was very close to these people — and it touched every part of my worldview, including my work, and resulted in questions that impact the way I think about storytelling. And these are questions that touch every storyteller, and that I ask you to think about as a jumping-off point:

Who owns the right to tell a story (and by this, I do not mean to imply copyright ownership)? Who gets to control the narrative of a story that has touched you directly? How much does shame come into play?

What does permission to tell a story mean?

How can we grant ourselves permission to write the stories we’re compelled to tell when we’ve been told (or it’s been implied) we shouldn’t?

When is a secret not a secret?

Should the storyteller bear the burden of secret-keeping or secret-telling?

How much does fear play a role in choosing or not choosing to write (or paint, or compose music)?

What happens if we overtly ask permission to write a particular story, and that permission is denied? Where do we go from there?

This is a universal issue. I have been a teacher of memoir now for almost a decade, and every student who attends my workshops first introduces themselves, talks about where they are from, a bit about their background, and what they are at work on in their writing lives. And then, without fail, almost every student says that there is something that they want to write about, that they need to write about. Yet: They can’t. An impossibility. They would vaporize on the spot, even if this thing they need to write about has defined them and their worldviews, and even if all parties involved are long dead.

They’ll reason with the gods: they’ll make it fiction, they say, and that way no one will ever know what or who they’re talking about. Or they’ll hide it in poetry and disguise their story in a villanelle. They’ll write it as a one-act play. They’ll take a pseudonym or joke about going into witness protection. Not one of these possibilities will work; when it comes to these crucial stories that make us who we are, they will be told and told slant, or told straight. Because they must be. I compare trying not to tell a crucial story to trying to stuff a live octopus into a pillowcase: you get one leg in, and another pops out. Over and over.

When my students arrive in class, they often cannot stop thinking about this thing they must tell; they write like their hair is on fire. And then, when they do stop for a breath, they remember the complications: the elderly parent who doesn’t want The Thing to be written about; the threatening spouse who is fighting for custody of the child, just because they can; the deep-seated guilt for toe-dipping into the story that generations have made it a point to hide; the distant cousin you see only at weddings and funerals who will say that it never happened and call you a liar, and just like that, your days of going to Thanksgiving dinner are over. But writers and art-makers are by nature drawn to the creative act of making meaning out of chaos, and the ideal creative experience that any of us ever have is art-making-as-compulsion. How many of you have had the experience of sitting down to create something — an essay, a musical composition, a visual work, a cake — and it’s noon when you begin and three pm the next time you look up, and you have no idea what happened to that time? Art-making-as-compulsion. The necessity to create takes over. An ideal situation often described as being in the zone. And yet we still must face the naysayers, and we have to make the decision. Do we create, or don’t we? What are we afraid of?

The act of writing memoir or personal narrative can be terrifying, and—I am sorry to say—these feelings do not ever abate; at best, we learn to live with them, cope with them, excavate them, metabolize them. It is understood, although rarely elucidated (except quietly, in whispered hushes, and mostly in therapists’ offices), that much of the fear of writing memoir has to do with warnings so ancient that they have become embedded in our psyches. We might be called a liar, a fabricator, a falsifier-of-the-truth. We may be told that the personal essay we’ve written comes from a grudge: you really hated that third cousin once removed, and so you’ve decided to tell the story about why she was sent away for a while when you were teenagers. We may be told that it’s just about revenge: your mother was so hideously cruel to you that you’ve decided to write about her so that everyone knows she’s not the perfect church lady everyone thinks she is, and now she’s too old to fight back.

But whoever we are and however seasoned we are in the work we do, the central component of this fear of writing, of what people will say, comes from shame. Together, fear and shame will conspire to quash creativity at every step, and they will, if we allow them to. How do fear and shame play a role in making the choice to write? What happens if we ask permission to write a particular story, and that permission is denied? (Imagine this scenario: Dear X: May I write a memoir documenting your abusive treatment of me as a child?) How many vital stories are not being told—memoirs written, movies made, art made, souls healed—because of fear and shame?

Early on, writes Jayne Anne Phillips in her essay Outlaw Heart, writers were awarded possession of a set of truths, enlisted to protect someone’s version, yet we lived in the context of those stories and we understood the truth to shift. And from the earliest days when I imagined that I might become a writer, this story of my father’s abandonment and how it directly affected me was the one that I knew I had to unravel, unpack, and attempt to fathom. The possibility of abandonment became a part of my life like the color of my eyes and my height, but it also became the family koan, the family threat, the silent terror around which our lives were wrapped. This was the story that I had to understand in order to keep, as Phillips wrote, sorrow from being meaningless.

Humans hew naturally to codification, and we write memoir — we make art — for this reason: To make sense of the chaotic. To corral the wild horses. To order the disordered. In my case, shame coursed through our century-old story of abandonment like lava, and my father metabolized the shame not by hiding it the way his sister had done, but through the telling of it because he knew, intuitively, that light and truth dilute and ultimately render shame and destruction powerless. They obscure them, like an eclipse. My father passed this knowing along to me, and now I pass it on to every writing student I have worked with over the last decade: handled with care, light and truth move writers and art-makers to a place of compassion, humility, self-knowledge, and transcendence. And that is why we do what we do.

(The prompts begin below, for paid subscribers. I have tried to figure out a way to allow free subscribers to comment, but Substack unfortunately limits this. Until I have it sorted out, please comment in Notes, where I will also be publishing this.)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Poor Man's Feast to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.